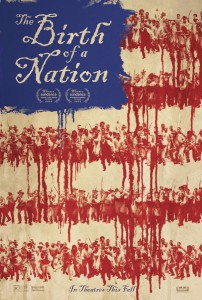

Film Review: The Birth of a Nation

For those Christians who gave the subject much thought at the time, the American Civil War was perceived as a crisis of theology. Crusaders campaigning to abolish the social evil of slavery and apologists invested with the task of defending it both employed scripture to defend their positions. For every passage that justified a slave submitting to his master, there seemed another compelling him to insurrection (or at least commanding the master to practice kind authority over his slaves, particularly if the slaves themselves were Christians). Nate Parker’s new film The Birth of a Nation revolves around this theological dispute. Based on the life of Nat Turner and his historic slave rebellion of 1831, the film portrays a man struggling to preserve his dignity through his faith in a world of horror and humiliation.

At the beginning of the film, the wife of Turner’s owner discovers that young Turner has learned to read. Nat’s mother apologizes for her son’s sin against the established order, but rather than outrage, the slave owner’s wife shows compassion for the boy’s interest in learning. She takes him under her tutelage by having him practice reading the Bible with her in the main house. When Nat enters the master’s study for the first time, he reaches onto the shelf for another book but is stopped. These are books for white folks, she tells him—ones he couldn’t understand.

Soon, Turner is reading Biblical passages in front of white congregations, and not long after that he’s preaching for his fellow slaves. He’s an adult now with the sober face of a scholar, the unsettledness of a prophet, and the build of a knight’s squire. “Wait for the Lord” is the central message of his slave kennel sermons. The righteous means at the disposal of a Christian slave to rectify his Christian master’s transgressions against him are not of this world or the next. The white congregation’s reverend hears of Turner’s instructional emphasis on slaves obeying their masters and proposes to Sam, Turner’s current master and the son of his now-deceased former master, that he ought to sell Turner’s services to other plantations to counsel their unruly slaves into obedience.

Turner’s own plantation is depicted as relatively sanguine. During his childhood, Nat plays hide-and-seek with young Sam, whose father protects Turner’s family against the brutish and malignant sheriff when he enters their slave quarters to question the family on their father’s whereabouts. The plantations Turner and Sam visit, however, are sanctuaries of misery and regimentation. Masters hover over their slaves in the field, rhythmically cracking their whips as the terrified slaves bloody their hands on the cotton branches’ dried bristles. A slaveowner’s daughter walks her servant girl on a leash tied with a noose’s knot. Two slaves are shackled to the wall in the cellar of a barn, and when one of them refuses to eat, his teeth are chiseled out and food is forced down his bloody mouth through a funnel.

The tour is profitable, but Sam is disturbed by how the other masters tyrannically abuse their slaves, and Turner feels within himself that the Bible should offer (or does offer) the slave more than false comfort in future divine restitutions.

Turner eventually finds a wife—a young girl who is almost sold at auction to one of the crowd’s groping buyers before Sam sees Turner’s discomfort and purchases her for his (Sam’s) sister—and the two have their first child together. Turner’s wife, Cherry, is eventually harassed and assaulted by the same sheriff who earlier hunted down Turner’s father.

At this point, loyalty to Sam is the only thing stopping Turner from retaliating against the brutality and injustices of the other plantations and for the crimes of violence brought against his wife by the local law enforcement. This fidelity ends, however, when Sam allows another slaveowner he has over as a guest to rape the wife of Turner’s friend. Turner acts out, baptizing a white man who stumbles upon the plantation looking for repentance. “To stand between the Lord and his people,” Turner tells Sam’s sister when she questions his right to do this, “is a dangerous place to be.” Once he finds out what Turner has done, Sam whips him in front of the rest of the plantation’s slaves. What’s left to take place—hardly but fifteen minutes of the 120-minute film—is history: embellished, established, or otherwise.

The historical record on Nat Turner’s life is unsurprisingly thin. No one cared who he was—merely a short, brooding slave with an uncouth fanaticism for the Holy Spirit—until he violently imposed himself onto history’s consciousness. William Styron’s The Confessions of Nat Turner is written from the perspective of a white Southerner, tormented like other Southern writers by the folklore of their upbringing and the acquired knowledge of its falsity. Styron’s Turner spends his time in servitude fantasizing about raping white women, and only after it’s essentially thrust upon him by external circumstances, does he bumble through his own rebellion. Nate Parker’s Turner is almost perfectly opposite Styron’s (at least if the opposite side of heads is tails): reserved but lucid, visionary but practical, courageous but self-conscious. Parker’s Turner is a loyal husband and a devoted father; his rebellion fails only because he’s betrayed by a young boy in his ranks.

If the film revolves around the theological correctness of slavery, what revolves around the film is the question of how Turner’s meek masculinity can survive the humiliation he and his family suffer daily. What’s a man to do as he and the ones he loves languish inside the belly of a beast? Other reviewers have expressed resentment over Parker’s putting the question solely in masculine terms. Whether because of Parker’s fixation on male responsibilities, or because he’s the director of the film as well as its star, the women of Birth of a Nation are little more than damsels in need of rescuing. Oddly enough, Parker’s movie shares this element of male paternalism with its racist namesake—a central component of D.W. Griffith’s 1915 drama is the moral obligation of white knights (i.e., the Ku Klux Klan) to protect white women from black predators.

Reviewers have also worried about the amount of violence in the film, an odd concern given how little of it there is. What violence does occur, however, adds to the narrative experience rather than distracts from it.

The theological dispute over the Civil War is still in effect debated today, albeit further downstream. Now, rather than asking if the Bible condones slavery or not, theologians and their followers ask if the problem of slavery couldn’t have been better solved by “Gospel gradualism” rather than revolution and war. In other words, more phony pontifications and denials of obvious truths. If defenders of slavery had been honest with themselves before the Civil War and Reconstruction, and admitted that they were interested in the perpetuation of injustice against black Americans because they feared that injustice would be returned to them once their reign ended, rather than conjoining their cause to political chicaneries (tariffs, state rights, imperial expansion in the Western hemisphere, etc), perhaps much bloodshed and misery could’ve been avoided. Perhaps Nat Turner could’ve been avoided. Instead, he became inevitable.