Film Review: The Case for Christ

Since I started writing film reviews, I’ve done three on movies that could properly be labeled as “right-wing,” either in a religious or political sense: God’s Not Dead 2, Hillary’s America: The Secret History of the Democratic Party, and The Shack. In each case I went to an opening-weekend showing and watched the film in nearly empty theaters. There were no more than ten other people watching The Shack with me; five with Hillary’s America (and two of them left within the first half hour); and for God’s Not Dead 2 I had the theater to myself.

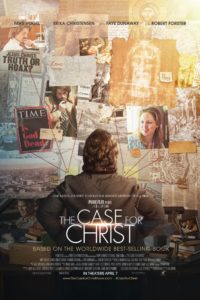

So you can imagine my surprise this weekend when I went to see The Case for Christ (directed by Jon Gunn and inspired by Lee Strobel’s 1998 bestseller of the same name) and was told that both remaining shows of the evening were sold out. Manipulating book sales has been a common practice for years, especially among Christian authors. For example, Robert A. Schuller (Walking in Your Own Shoes), David Jeremiah (Captured by Grace) and Mark Driscoll (Real Marriage: The Truth about Sex, Friendship, and Life) were all caught using “marketing firms” to make bulk purchases of their books in order to get them on the bestseller lists. And no doubt a similar shady practice is done when it comes to the movie business. But when I got to the second theater (ten miles from the first), the ticket-seller told me their last show was full except for the front row, and when I got inside the actual theater, it wasn’t me and a room full of ghosts.

The Case for Christ is the conversion story of Lee Strobel (Mike Vogel)—how he went from an atheist Chicago Tribune reporter to one of the country’s most recognizable apologists for the Christian faith. One can trust Strobel’s depiction of his conversion, since it seems too unbelievable to be imaginary. After his daughter is saved from choking on a gumball by a Christian woman, Strobel’s wife Leslie (Erika Christensen) is convinced that God led the woman to the restaurant that night to save the girl. Leslie starts going to church with the woman and eventually tells Strobel that she’s converting to Christianity. Being the disgruntled, dogmatic atheist that he is, Strobel decides his best chance at de-Christianizing his wife is to definitively prove that the resurrection didn’t happen.

He talks to archeologists, psychoanalysts, and medical doctors in order to gather evidence for his negative case, but everyone he talks to agrees that the facts suggest Christ died on the cross and was resurrected days later. There’s obviously quite a bit of ham-fisted pedagogical exposition in these scenes. The archaeologist explains to Strobel what “textual criticism” is. The medical doctor goes into anatomical detail as to why Christ certainly could not have survived the flogging and crucifixion. And the psychoanalyst proposes that father issues might be the root cause of skeptical animosity toward religion. She tells Strobel that Hume, Nietzsche, Freud, and Sartre all either lost their fathers at a young age or, for whatever reason, had disapproving views of their old men. Strobel collects all this evidence in a secret study in the boiler room of the Chicago Tribune’s building. Books are stacked on the tables, dry erase boards are crowded with potential leads and yarn strings link potential inconsistencies. At last, overwhelmed by all the data that Christ died and was reborn, Strobel tells his wife what he’s been up to (their marriage until this point was slowly falling apart) and that he would like to become a Christian too. From henceforth the Lord’s Prayer in the Strobel house would be: Give us this day our daily fact.

No one will be convinced (or should be anyway) by the evidence presented in the film. Strobel puts forward a very compelling case that the gospels affirm the crucifixion and subsequent resurrection of Jesus. But I wasn’t aware many folks doubted that they did. The archaeologist Strobel visits tells him the gospels have more accurately recorded copies than any other classical document—even more, he emphasizes, than the Iliad. What this is meant to prove, besides that Christianity as a social movement perhaps had a strong emphasis on pamphleteering at its beginning, is anyone’s guess. All the careful copies in the world don’t make what the original says true. Just ask Mao or Lenin.

Nor does it mean much to have in your possession a few books that all claim there were hundreds of eyewitnesses for the resurrection. Even if there were hundreds of eyewitnesses, which the books don’t prove simply by agreeing with one another, that still doesn’t mean Jesus was resurrected. Impersonation, mass delusion, or standard Bronze Age mythopoeia are all more realistic alternatives than the biblical account. Resurrection—along with miracle work, virgin birth, and divine parentage—were part of many prophetic narratives at the time. And although Strobel’s psychoanalyst assures him that “mass hallucinations” cannot happen, delusions are very different than hallucinations and happen in mass more often than professional crowd-pleasers (like Strobel) care to admit.

The Case for Christ’s decent box office showing can be attributed in part to its trailer. It portrays the film as part Dan Brown-esque supernatural thriller, part A&E-style historical nonsense, and part quotidian family drama about a spouse’s sudden religious conversion. What the film actually is, however, is a stroke of personal and national vanity, playing up Strobel’s divine preordination and our national character’s alleged preference for fact over theory. “The only way to truth is through facts,” Strobel says in the film’s first scene—a banal sentiment as self-serving as it is disingenuous.