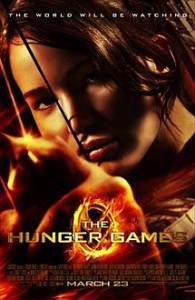

Film Review: Does The Hunger Games Depict a Godless Society?

In this wildly popular film, based on a novel of the same name that is part of a trilogy, the lead character is a young woman, Katniss Everdeen, played by Jennifer Lawrence. Katniss lives in District 12, the poorest of Panem, a dystopian future nation carved out of North America. Because the central government wishes to keep the districts in line and avoid a repeat of a rebellion from the past, it takes an annual tribute of one young woman and man from each district, forcing them to engage in a televised free-for-all killing spree in a forest-like arena set up for the purpose. The tributes are drawn by lot, but someone else may volunteer to take a given tribute’s place in the games. And that’s what Katniss does when her younger sister’s name is drawn.

From this point on the movie largely becomes a survival adventure story with very little to say about anything else (except that oppressive societies with cruel forms of entertainment are bad and that underdogs with humanitarian and communitarian values are good). Although Katniss finds a way to thwart one of the aims of the government in the way it puts on its games, and thus to express her independence and take a stand for her district, the film is largely predictable and uninspiring.

So why write about it? Because the primary interest this particular blockbuster release can hold for humanists is that the society depicted appears to be a secular one. And since this society is evil, then it’s an easy step for evangelical Christians to use the movie to illustrate what America might become if humanism were to triumph. Indeed, this gambit has already been tried.

But is the world of The Hunger Games really a secular one, or is religion simply not addressed in the narrative? Jeffrey Weiss, a columnist for RealClearReligion, argues that the one proves the other. Noticing that the film, and the novel trilogy behind it, make no mention whatever of God or any supernatural beliefs, and how there’s “no ritual that isn’t totally grounded in some materialistic purpose,” Weiss concludes that “such an unequivocal expunging can only have been intentional.” Why? Because in the novels and film there are so many “fine details about fashion and food and weaponry and the shape of furniture and the color of dust” that religious detail is made conspicuous by its absence.

However, if we accept this logic, we have to apply it across the board—not only to the dominant evil society in the story but to those characters who, in being oppressed by this society, rebel against it and wish its overthrow. They have no religion either. Secularity seems a characteristic of both villains and heroes. And that leaves nothing for evangelicals to latch on to.

Not that it would matter if the novels and film made the good guys religious and the bad ones secular. It would prove nothing because this is all fiction. Reality is much different. In our world we find such things as brutal religious regimes in the Middle East that impose sharia law contrasted against secular social democracies in Europe that are open societies. Hence we have little need for moralistic what-ifs, sourced in dystopic sci-fi literature and cinema, to guide us.

Moreover, one of the models for The Hunger Games is the ancient Roman gladiatorial contests. Indeed, the whole society is in many ways fashioned after Rome, to the point that the main characters in the story’s capital city have such names as Caesar, Cato, Cinna, Claudius, Coriolanus, Flavius, Octavia, Portia, and Seneca. But ancient Rome wasn’t a secular society. Its emperors doubled as the chief priests, there were many local gods among the people as well as a plethora of bizarre religious practices, soothsayers were called upon to prophesy the outcome of every battle, and public superstition was so rife that even the skeptics of the time tended to hedge their bets with occasional rituals. Therefore, we have no historic model for a secular society that ever had anything resembling the cruel games in this movie.

Unless you fudge a little and count American society with its passion for such “reality” television shows as Survivor. This show is, indeed, the main other thing the movie is based on. The world of novelist Suzanne Collins’ Hunger Games has been called a blending of the above plus the film The Truman Show, such novels as The Moon is a Harsh Mistress by Robert A. Heinlein and A Wrinkle in Time by Madeline L’Engle, and the Shirley Jackson short story “The Lottery.”

The blend makes for a trilogy that has put 26 million books in print. But it still says nothing about humanism, which is as opposed to oppressive societies as it is to the superstition that, in the real world, often underlies them.