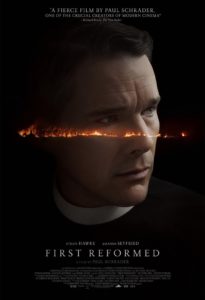

Film Review: First Reformed

How many sins can a person commit in the name of a righteous cause before the sins outweigh the cause? This is the central moral question of Paul Schrader’s new film, First Reformed. In secular terms, the question is the ancient conundrum of the relationship between means and ends: Is it right to lie to an agent of the state to protect a fugitive? Or to derail a military train delivering equipment to a genocidal war? Or to murder a slave-master? Or a tyrannical leader?

As First Reformed suggests, there are no easy answers—or places to look for easy answers. St. Paul said to obey the powerful; but Jesus himself rebelled. (As H.L. Mencken pointed out, the criminal sign posted above Jesus’s head was “King of the Jews,” not “Son of God”—implying that the Romans executed Jesus for his political dissent rather than for his proclaimed divinity). And as much as philosophers and would-be philosophers like to imagine morality is a calculus, it’s actually much more a set of intuitions—intuitions that are, at best, tactical, nuanced, and routinely interrogated, and at worst selfish, secondhand, and born from fear and ignorance.

Schrader, who wrote and directed First Reformed, is best known for writing the screenplays of Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, and The Last Temptation of Christ. His reputation is that he’s a master of cinematic mood-setting, and in First Reformed that reputation is well-deserved. He establishes mood primarily in two ways: through cinematography and pacing. He lets shots linger. The camera will stay on a scene until the character walks off screen, or stay on a characterless scene until one of the characters returns, or focus on the face of a character even after he or she is done talking. These directorial choices give a realism and sturdiness to Schrader’s movies that tighter, more sharply cut movies don’t have. Actors are depended on to capture the physical unease that Schrader’s petty tragedies bear upon them. Some actors in Schrader’s previous movies didn’t always deliver, but the cast of First Reformed absolutely does.

Unfortunately, the film’s story is much better than its actual plot execution. A downfall of Schrader’s patience with the camera is that narrative elements can feel rushed: necessary details get expressed in stuffy exposition.

Ernst Toller (Ethan Hawke) is the reverend of First Reformed, a historically significant (it was a stop on the Underground Railroad) but now sparsely attended church in Snowbridge, New York. It’s been incorporated into a pastoral network anchored by the megachurch, Abundant Life, which is led by Pastor Jeffers (Cedric “The Entertainer” Kyles). First Reformed is mocked by the staff at Abundant Life as “the museum” and “the souvenir shop.” Rev. Toller gives more tours than sermons.

When the movie begins we are eight weeks away from the 250th anniversary of First Reformed. Abundant Life is planning an extravagant reconsecration ceremony, where people with power—the mayor, the governor, wealthy donors, and church elders—will be in attendance, while everyone else will watch it through video at Abundant Life. Before that, however, Toller is introduced to Michael (Philip Ettinger), a troubled young man neurotically obsessed with ecological doom. He’s first contacted by Michael’s wife Mary (Amanda Seyfried), who’s worried about her husband and pregnant with their child. Michael doesn’t believe it’s right to bring a child into the world given what we know about global warming and wants Mary to get an abortion.

Toller meets with Michael in what is perhaps First Reformed‘s most potent and subtle scene. Neuroticism even for a good cause is still bad for the human spirit, and Michael’s obsession with global warming is destroying him. He asks Toller if he believes in martyrdom, then tells him about different environmentalists who have been murdered for their activism. He feels guilty for not doing more himself but also hopeless that anything more can be done at this point anyway. Is it egotism or morality that flames Michael’s despair? Does the motivation matter?

After the meeting between Toller and Michael, Mary discovers a suicide vest in the couple’s garage. Through death and controversy, Toller becomes immersed himself in the moral dilemma of means and ends on how to stop the ecological destruction of God’s creation. His dilemma is complicated by the revelation that Balq Industries, one of Abundant Life’s biggest donors, is also one of the world’s worst polluters.

“Courage is the solution to despair,” Toller tells Michael at one point. “Reason provides no answers.” Toller’s despair comes from loss and isolation. His wife left him after their son was killed in Iraq. She was against their son enlisting but Toller encouraged it as a patriotic responsibility of the family: he had served in the military just as his father and grandfather had, and so should his son. Now he lives alone in a near-empty house behind his church. He’s a monk living in an age of martyrdom. His monastic lifestyle is an adversion from the recognition of his own powerlessness.

First Reformed encapsulates the American mood. There is fanaticism or complacency. “Jihadism is everywhere—even here,” Pastor Jeffers tells Toller, referring to the ideological anger of people at Abundant Life, especially among the young. During a youth group meeting, Toller is harangued by a teenager for saying that godliness doesn’t guarantee prosperity. The angry teen complains about people on welfare and how no one is allowed to “offend” anyone anymore (especially “the Muslims”). Toller doesn’t know how to respond. At that point, his own heart is filled with helpless anger as well.

First Reformed is an accomplishment. It is “serious” without being conceited or boring. Its central moral question is about the human heart, but Schrader isn’t afraid to give the question a contemporary expression for fear of being “too political.” Rev. Toller has no control over his world yet he suffers not only from the consequences of decisions made by others but from his own guilt at not fighting to have more say in those decisions.

What should one take away from First Reformed? That people feel isolated yet exposed—and that people in such a condition for long enough will welcome the apocalypse, environmental or otherwise. “You think God wants to destroy his creation?” Toller asks his fellow clergyman, to which Jeffers responds, “He did once.” And, in Christianity, we’re all created in the image of God.