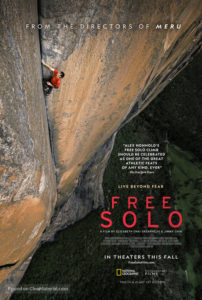

Film Review: Free Solo

The cinematography alone is reason for an unacquainted viewer to see the 2018 climbing documentary Free Solo. The film documents thirty-three-year-old American climber Alex Honnold’s pilgrimage to climb El Capitan: the 3,000-foot vertical sheer granite wall in Yosemite National Park, California. Honnold, staring into the abyss, strives to climb the peak alone and without ropes, a feat never accomplished before.

Filmmaker couple Jimmy Chin and Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi, known for their 2015 film Meru (Audience Award at the Sundance Film Festival), illuminate Honnold not as an indomitable climber, but rather as a damaged, deeply troubled man who has extraordinary talent and unfathomable nerves (an MRI determines that he needs more stimulation than rest of us).

At first Honnold appears as an improbable extreme climber. The introverted kid full of self-loathing and insecurities still lives in the adult mountain climber. But those very characteristics, and possibly Asperger’s as his mother suggests, amalgamate to form one of the finest climbers in the world and probably the best free solo climber ever. And, undoubtedly, the riskiest.

The National Geographic film, which embraces the man versus nature archetype, is ultimately, then, about Honnold, and not El Capitan. The film explores the early life of the obsessive and passionate climber who has lived in a van for a decade. Unhugged as a child, Honnold battles his demons while pursuing his dream of conquering El Capitan. He struggles to be understood, even within his own professional climbing circle (no one really wants him to do it), and to have real human connection, let alone to love another person. While preparing for El Capitan, Honnold apprehensively searches for a home with his girlfriend, Sanni McCandless, in Las Vegas. The home, clearly, is for her; Honnold is mildly resistant to making the purchase but tries to push himself to embrace some semblance of normality.

When talking to McCandless about the dangers of soloing, Honnold says, “If I had some kind of obligation to maximize my lifespan, then yeah, obviously I’d have to give up soloing.”

“Is me asking you—do you see that as an obligation?” she asks. The conversation unfolds in Honnold’s conversion van.

“To maximize lifetime?” Honnold responds. “No, no. But you saying, ‘Be safer.’ I’m kind of like, ‘Well, I’m already doing my best. So I could just not do certain things, but then you have weird simmering resentment because the things you love most in life have now been squashed. Do you know what I mean?”

Is it possible to balance one of the most extreme, unsafe athletic pursuits with a long-term romantic relationship?

Before the sunrise one morning, Honnold heads out to El Capitan with a flashlight on his head. He begins the ascent quickly, matching his footings with the climbing journal in which he’s been intricately mapping the route during his roped preliminary climbs. One thousand feet up, he quits. A conversation with filmmaker Jimmy Chin and the others ensues: Is it possible for Honnold to make the climb without the process of filming impacting the climber? Should it be filmed at all? The audience is left wondering whether Honnold will be able to pull it off.

With incredible clarity and beauty, Chin and Vasarhelyi’s film work captures the intricate placement of toes and fingers that keep Honnold alive over the magnificent California void. The audience is left wondering how a shy kid from Sacramento can conquer a monstrous cliff face that no one has ever climbed before without a rope.

Honnold’s compulsion to tackle peaks freely and unprotected puts him face-to-face with mortality. Asked by Rolling Stone about the link between his atheism and his perspective on death, Honnold states:

I’ve certainly thought about my mortality more than most. I think some people turn to faith as a crutch, to avoid thinking about mortality—you know, ‘Well, I’ll carry on forever in some eternal kingdom.” But the harder thing is to stare into the abyss and understand that when it’s over, it’s over.

Honnold’s reflection upon nature—that it just doesn’t care when, as a human being, you’re staring into the abyss—is refreshing. Maybe Honnold’s greatest feat is not soloing any particular peak—even El Capitan—but rather his ability to accept mortality for the reality it is.