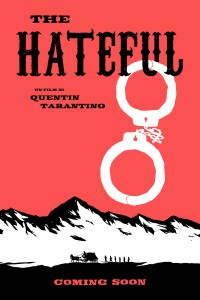

Film Review: The Hateful Eight

Quentin Tarantino films have a way about them. They are talky, violent, satirical, nostalgic of the 1970s, and excessive—populated as they are with despicable characters, including the protagonists, who know how to talk the talk of the disreputable walk they walk.

Now comes Tarantino’s latest, The Hateful Eight, in throwback “roadshow release,” complete with 70mm Ultra-Panavision format, opening “overture,” an intermission, absence of trailers, and a promise of a shorter, trimmed down version for its future “general release.” (Those born after 1970 will have little idea what I’m talking about here. But I really wish there’d been an in-theater souvenir program to go with it. I’d have bought it in a heartbeat!)

I went to see The Hateful Eight on Christmas. Why? Because it’s a Christmas movie, of course—a ruthless spaghetti-style western set in snowy Wyoming to strains of “Silent Night” played with faltering hesitancy on an out-of-tune piano by a criminal gang member.

It all starts, reminiscent of the opening scene in Battle of the Bulge (1965), with a wide panoramic shot of snowy landscape. Then, a stagecoach, like the lone car that opens the equally neo-noir Fargo (1996), gradually appears from the distance to slowly become a focus of attention.

This stagecoach has been reserved at some expense for the exclusive use of bounty hunter John “The Hangman” Ruth (Kurt Russell) and his prisoner Daisy Domergue (Jennifer Jason Leigh) enroute to Red Rock where she’s to be turned over for a $10,000 bounty, a trial, and a hanging. But because a blizzard is on the stagecoach’s tail, these travelers will do well to reach an isolated way station in time, quaintly named “Minnie’s Haberdashery.” Such progress is nonetheless interrupted by an encounter with another bounty hunter, Marquis Warren (Samuel L. Jackson), a former Union major in the late Civil War, and then by the incoming sheriff of Red Rock, Chris Mannix (Walton Goggins), a former Confederate marauder. Despite these competitive interests and historic animosities, the four (besides the driver) manage to stay just cordial enough to occupy the same stagecoach and reach the way station.

At Minnie’s Haberdashery they encounter four more characters: Bob (Demian Bichir), Oswaldo Mobray (Tim Roth), Joe Gage (Michael Madsen), and former Confederate General Sandy Smithers (Bruce Dern). Do the two groups of four (not counting the driver) add up to the “hateful eight” of the film’s title? Well, they are all shown to be pretty hateful. But other characters make appearances, mostly in flashback, and at least one of them is pretty important and awfully hateful too. So I think the title is actually derived from the fact that this is billed as Tarantino’s eighth film (he says he’ll only make ten), and some people really hate his work.

Certainly this is Tarantino at his most Tarantino, which means it definitely isn’t a film for the squeamish. I’m sure the n-word has never been used so many times in one film in the entire history of cinema. He must have decided to go for the record. The Hateful Eight also contains continuous abuse (and multiple murders) of women, approving references to torture and terror, male frontal nudity and simulated oral sex, and all the gratuitous carnage of a splatter film. (But no animals were harmed or even made to look like they were.)

So what’s the point? Where’s the artistry and social consciousness that would interest a humanist like me? The answer is, everywhere and throughout.

In this film we are exposed to what racism and sexism look like when regarded as approved behavior. We peer into life as experienced and survived by racial and ethnic minorities. We see the effects of war on the human psyche and learn the ruthlessness of combat itself along with the suffering of war prisoners. And we witness the ease with which innocent people can be made victims of organized criminal activities.

Then there are the philosophical moments. I said Tarantino films are talky. So we are treated to an explanation of justice as a concept, observe skepticism at work in exposing a sham, and learn the value to oppressed people of calculated dishonesty.

Moreover, as a film with a small but diverse cast, we see the Old West as we’ve rarely seen it before. There are capable women (stuntwoman-actress Zoë Bell plays stagecoach driver Six-Horse Judy and actress-singer-songwriter Dana Gourrier is businesswoman Minnie Mink). There is a happy interracial relationship. And a black man demonstrates that he’s the smartest guy in the room as he turns this western yarn into a whodunit murder mystery.

But overall, the film is an exercise in social and cinematic satire, with much of its offensive language, abusive behavior, and outrageous violence more comical than serious. Thus in The Hateful Eight, Quentin Tarantino shows us once again that he knows how to take it over the top without toppling over.