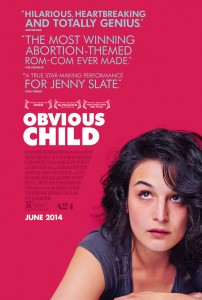

Film Review: Obvious Child

As a groundbreaking indie romantic comedy about abortion, Gillian Robespiere’s Obvious Child has provoked both praise and criticism. Blogs such as Jezebel have applauded the film for its straightforward approach to a controversial subject. However, the Family Research Council, a conservative Christian policy group, decried the film’s subject matter as “a grave moral evil.” This criticism, to humanists, may actually increase interest the film. Anyone truly interested in women’s issues will likely walk away from the theater chuckling while recognizing that, in its honest portrayal of abortion and everyday life, the movie succeeds in humanizing women and normalizing abortion.

Obvious Child tells the story of Donna Stern (Jenny Slate), a stand-up comic who isn’t afraid to offer up intimate details of her life to audiences in a Brooklyn dive bar for laughs and attention. The movie opens with her set about old underwear and trying not to fart on a first date. (If you don’t enjoy coarse humor or toilet jokes, this may not be the film for you.) Shortly afterwards, she is dumped by her boyfriend, who reveals that he’s been cheating on her. The next day, she learns that the bookstore where she works will be closing. Understandably upset, Donna gets drunk and has a one-night stand. Several weeks later, she discovers that she’s pregnant and decides to have an abortion. She is supported in this decision by her roommate (Gaby Hoffman), a fellow comic (Gabe Liedman) and her mother (Polly Draper). Comedian and atheist David Cross also makes an appearance.

While much of the movie’s action takes place during the week in which Donna is waiting for her appointment at the clinic, Donna herself is not defined solely by her decision to terminate her pregnancy. Instead, she is presented as a fully realized character, with strengths and flaws and hopes and dreams. She is attempting to navigate life as a twenty-something in New York City and grow out of her extended adolescence in response to her mother’s concerned nagging. She is hilarious, but many of the laughs she elicits from the audience are based not only on shared humor but also on shared experience. With her crass stand-up routines and wry quips, she subverts the stereotype of the typical, one-dimensional romantic comedy heroine. Rather than being conventionally feminine, cool and flirty, Donna is candid, crude, and awkward with her love interest Max (Jake Lacy). As the film portrays her, Donna is, first and foremost, a human being—who just happens to be getting an abortion.

By humanizing Donna, the film not only undercuts Hollywood’s typical representations of women but also avoids turning the film into a public service announcement about safe sex or a political diatribe in favor of abortion. Instead of politicizing abortion, Obvious Child normalizes it. This depiction of abortion is assertive and positive. It doesn’t defensively make a case for Donna’s choice in the context of religious viewpoints about the supposed right to life of the fetus or immorality of premarital, casual sex. Instead, the film simply ignores the religious right’s position on abortion. The focus is entirely on Donna, the fetus isn’t a character at all, and anti-abortion claims are not even considered. This positive message about women’s reproductive rights is especially important in light of the recent U.S. Supreme Court decision on Burwell v. Hobby Lobby, which ruled an employer’s religious beliefs can get special privilege at the expense of female employees’ full access to contraceptive healthcare. In proactively presenting abortion as normal, Obvious Child reveals itself to be a truly humanist film that shows a woman making her own decision in a secular society, free from condemnation by religion.

If you’re looking for a raunchy comedy that combines strong female characters with humanist themes as well as a little bit of romance, then Obvious Child is probably the summer flick for you. A listing of theaters where it is playing can be found here.