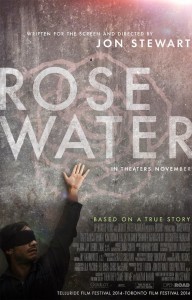

Film Review: Rosewater Jon Stewart Didn’t Want to Make a Movie—He Wanted to Make THIS Movie

Let me say right off the bat—Jon Stewart seems like a really nice guy. When you watch him on The Daily Show he comes across as sharp, engaged and, of course, very funny. And he was all that in the Q&A following a recent screening of the film Rosewater (his directorial debut) at Georgetown University in Washington, DC. But he was also just really nice. He didn’t even heckle the couple of students who, when it was their turn at the mic to pose a question, turned first to snap a selfie with Stewart in the background. (I actually wish he’d heckled those students, but that’s my issue.)

Stewart’s graciousness and earnestness come through very clearly in Rosewater, a recounting of the imprisonment of Maziar Bahari, an Iranian-born journalist who returned to Tehran from London in 2009 to cover the presidential election for Newsweek magazine.

Just before election day, Bahari was interviewed by Jason Jones of The Daily Show in a bit where Jones pretended to be a spy, asked Bahari probing questions about the Iranian government, and pressed him to admit he was a terrorist. After Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was reelected and young Iranian supporters of the independent reformer Mir-Hossein Mousavi took to the streets to protest what many believed was a rigged election, Bahari immediately began filming and reporting on the so-called Green Revolution. He was also asked by The Daily Show producers if he was comfortable with them running the Jason Jones segment in the midst of all the tumult. He said he was.

And then the Iranian government imprisoned Bahari for 118 days. He was questioned about the interview, about his association with the United States, with the CIA, and so forth. Bahari dubbed his interrogator “Mr. Rosewater” (a member of the Revolutionary Guard fixated on illicit sex, Jews, and the state of New Jersey) after the perfume he sprayed on himself. Bahari was beaten and isolated, forced to confess that the media had hyped up the street protests, and then eventually freed.

Bahari has stated in interviews that when in solitary confinement you can see (when not blindfolded) and touch only the walls around you, and so you must go inside yourself to retain hope for release. While some prisoners tap into spiritual or religious sources, as a self-identified nonbeliever Bahari turned to the memories of his father, a social activist imprisoned during the Shah’s rule in the 1950s, and his sister, also an activist who was imprisoned by the Ayatollah Khomeini. Mining the absurdity of his situation and of his interrogator’s fixations also helped Bahari sustain hope for freedom. And he promised himself that he would write a book about his experience in order to bring attention to the similar plight of thousands of journalists around the world who are imprisoned at any time.

The Rosewater Q&A at Georgetown University

Bahari’s memoir, Then They Came for Me, was published in 2011 and provided source material for the Rosewater screenplay, written by Stewart. It wasn’t his intention to write and direct the film, but impatience with the slow pace of Hollywood financing and production brought Stewart to the decision to make it himself, with Bahari’s advisement. They filmed in Jordan (the prison scenes took place in a working prison) in what the actors, namely Gael García Bernal as the jailed journalist, have said was a very collaborative effort.

And Stewart does a fine job at the helm. One brief scene in particular showcases his talent for conveying much in a simple visual. It’s a scene after the election and before Bahari is imprisoned where his driver, a very likeable character who embodies the spirit of young, reform-minded Iranians, has stopped his motorcycle on the side of the road at sunset to pray. Bahari leans patiently against the bike, working. It conveys the nuances of Iranians who are both progressive and pious, and of a journalist dedicated to telling their story. (As Stewart noted in the Q&A, he’s the only person who prays in the film and he’s also one of the most relatable characters to Western audiences.)

For these reasons and more, Rosewater is a film you just have to applaud. My quibbles with the storytelling mainly involve the title character, Rosewater. While his quirks supply some oft-noted comic relief to the film, I felt his character wasn’t revealed to the extent it could have been. (The film is named Rosewater, after all.) Stewart has said that he wanted to show the banal and bureaucratic side of a regime and the office of interrogators, and in the Q&A described a scene where Rosewater goes into the break room at the prison and gets angry when he discovers someone has eaten his cucumbers and starts interrogating his coworkers. They had to cut the scene, Stewart said, but I wish it had been left in.

But that’s all part of the process of filmmaking, which Stewart amiably undertook to tell a great story. When asked if he regretted airing The Daily Show segment that was later used against Bahari, Stewart said no: “You can’t control what idiots leverage.” And when a Georgetown student stood before him and nervously said: “Woody Allen says he never watches his movies after they’re done. How about you?” Stewart deadpanned, “No. I never rewatch Woody Allen’s movies either.” And because there’s often a sincerity behind Stewart’s quips, he added, “but I’ve seen this one [Rosewater] something like 3,000 times.”