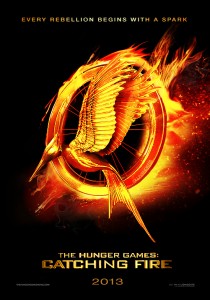

Movie Review: The Hunger Games

Chris Lindstrom reviews the second film of The Hunger Games’ franchise, out in theaters now, and highlights many of the book’s humanist elements.

In time for Thanksgiving, Jennifer Lawrence is back on the big screen as Katniss Everdeen in Suzanne Collin’s Hunger Games sequel Catching Fire. Yes, I’ve had tickets since October. I’ve seen the original Hunger Games movie twenty times, read the series three times and lost count of the number of times I’ve listened to the audiobook version. I’m unabashedly obsessed and I was fully prepared to love whatever cheesy Hollywood production emerged for round two. However, I found myself disappointed. The filmmakers, in an effort to leave no fan behind, crowded the film with as many scenes as possible, leaving each one feeling rushed.

What I love about the first Hunger Games movie and the book series is that it’s really a modern myth—just enough specifics to be interesting but enough gaps and nuance to allow the reader space to imagine. In the first film, Katniss is often quiet. We watch the gears moving in her mind. We grow as she grows. By contrast, the sequel has no quiet places, just an onslaught of the senses, one attack after another. No pregnant pauses after significant lines to absorb undertones. No time for human interaction. No time to ponder any larger meanings. When Katniss wonders aloud, “How can we kill these people?” the audience is left to wonder why she cares since the film paid short shrift to real human exchanges. Katniss’ recruitment of allies in the training center had all the subtlety of a grocery list. Check! Done! Next!

If I made the film, I would have cut at least half the scenes and slowed what remained down to human speed. I’d leave almost all of the scenes with Prim and Gale on the cutting room floor (sorry Team Gale). Also gone would be all scenes with President Snow and his deputy, Plutarch. Silent villains are more powerful and frankly, these scenes make Snow appear petty and melodramatic, rather than resolute. I’d cut some arena scenes too: the spinning island and the jabberjays. I’d leave out everything that happened on the hovercraft, ending simply with her being raised into the air while a voiceover from Haymitch worries about what will happen when she realizes they didn’t rescue Peeta as well.

I’d use the time saved to expand the silence and nuance in the remaining scenes, focusing on brief but meaningful human interactions. Katniss’ interaction with President Snow in the study would be expanded. Not in words, but in added silence between words. Pause and let us imagine for a moment what he means when he says the system is fragile but “not in the way you think.” Ditto for the scene where Finnick meets Katniss for the first time. As a Capitol sex symbol, “Do you want a sugar cube?” should be a slowly drawled pickup line and met with astonished silence. Expand the interactions with Betee and Wiress and Mags. Finally, I would have included the scene from the book where Katniss and Finnick play a practical joke on Peeta by waking him to the view of the scary, ointment smeared faces purely as comic relief. And, for the romantics, I’d have Haymitch utter Collin’s full line: “Every year they’ll revisit the romance… and you’ll never be able to do anything but live happily ever after with that boy.”

Nonetheless, the film actually did an excellent job of emphasizing one of the humanistic themes: cooperation as resistance, albeit in an overly heavy-handed way. The movie makes it clear as the tributes join hands at Caesar Flickerman’s interview night that this is a threat to the “divide and conquer” ruling strategy of the Capitol. Also clear is Finnick’s admonition to “remember who the real enemy is.” It’s ironic that President Snow starts the movie by asking Katniss to sell a story of love to the districts. Is he really ignorant that in a dog-eat-dog system, love itself is a rebellious act?

Also on display in the film is Katniss’ continuing ability to find a way out of the box the Capitol puts her in. She refuses to play to their script. In the first book, she threatens suicide a la Romeo and Juliet rather than kill Peeta. In the second, she shoots an arrow directly into the heart of the Capitol, shooting out their force field rather than her fellow tribute. Humanists too, like to pride themselves on “living outside the lines” of prescribed religious scripts. We prefer our life scripts self-directed and our ethics derived from evidence, reason and compassion. Women do not need to be submissive and disobedient children do not need to be stoned at the gates of the city. Is it possible, that in our world, much like the Capitol, acts of solidarity can be acts of creative disruption?

So, this holiday season, enjoy the movie for what it is if you’re so inclined. You can follow it up with the slower moving but more enjoyable audio book of the same name and wash it all down with a few revolutionary acts of your own making.