Mythology in Film: How Humanists Can Appreciate Religious or Fantasy Films

The lumbering, mindlessly hungry undead surround their victims, hoping to sink their teeth into living flesh. One bite will turn a normal person into a monster, and only a blow to the head will stop them from their unfettered cannibalistic feasting.

A vampire is an immortal, nocturnal beast, sucking the blood of defenseless humans in the darkness, fearing only sunlight and a stake to the heart.

The light of the full moon transforms a bitten person into a wolf.

When certain worldly signs appear, some people will be sucked up into a celestial afterlife, while those left on Earth will be forced to toil and battle with the forces of evil for the souls of the remaining humanity.

In fiction, especially science fiction and fantasy, there are certain mythologies which are perpetuated throughout the history of media after their inception. The novel Dracula set many of the rules of vampires that we recognize today. George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead, while originally meant as an allegory for racial tension in post-civil rights America, created a vision of the walking dead that has continued on in things like, well, The Walking Dead.

The governing ideas that exist within these archetypes have become so ubiquitous that audiences can see them in a sort of shorthand, a language or set of visual clues that we no longer need explained to us when they appear. In the cult hit comedy Shaun of the Dead, for example, they never use the word “zombie,” yet we as viewers understand exactly what it is they’re up against.

There’s a comfort in the commonality of these mythologies, a bit of communal thrill when the classic narratives and their rules are tweaked for new generations, as a show like True Blood has in many ways re-written the rules for vampires, werewolves, witches, and a whole host of mythical figures.

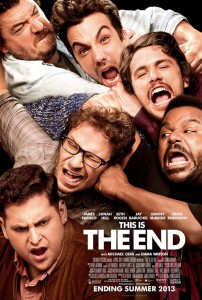

And while they might not think of it in the same terms, viewers can have a similar reaction when those classic stories are from none other than the Bible. When Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg’s uproarious apocalypse comedy This Is The End was released in June, there was a comfort in the way they gleefully tweaked the narratives lain out in the Book of Revelations.

It makes sense that a broad, popular comedy would utilize Biblical references to tell its story; the Bible is one of the most widely-read books in the history of the world. More importantly, it stands as the foundation for mythologies spanning millennia, from creatures like angels and demons to sets of unforgivable sins and an actual rulebook for living called The Ten Commandments.

Consider J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, and the world that author crafted, with hobbits and elves and dwarves and wizards and orcs and magical rings and evil all-seeing villains and new languages. Think of the new stories spawned from Tolkien’s inventions, and then consider the ideas originated in the Bible, and, for a humanist, they’re each equally ripe fodder for the creative imagination.

This Is The End succeeds by hitting on a notion of religious dogma as science fiction, as fantasy, as mythology, mining things like the Rapture, devils (in this case, devils with abnormally prominent sexual organs), even demonic possessions. And the audience barely needs the rules explained to them, because, much like the shorthand employed for zombies and werewolves, there’s enough of an established mythos that we can get it without needing everything to be spoon-fed to us.

This opens up a wealth of possibilities for humanist film lovers. Critics and careful viewers are often quick to note when a film presents a “Christ” figure, or contains some religious allegory. But what about the other side: The fantastical elements of overtly religious films? It’s time to dust off some Christian classics and start exploring some of their more “out-there” creative ideas.

You might find that The Passion or The Last Temptation of Christ make for great fantasy. Or that Defending Your Life or The Greatest Story Ever Told are fascinating sci-fi. Or maybe you’ll decide that you prefer the more consistent and entertaining stories of walking corpses or man-wolves or blood-sucking fiends or wizards or whatever you like. The point is that they can all be examined from the same frame of reference.

So the next time you’re watching a movie that contains some heavy religious content, don’t think about it as preachy, indoctrinating, or propagandistic. Just remember that they’re fulfilling classic archetypal rules, the same way zombie movies need corpses and werewolf movies need a full moon. Crosses signify Christian predominance, but they also burn the skin of vampires. It’s all fan-fiction, sprung from one mind to another, all for your entertainment.