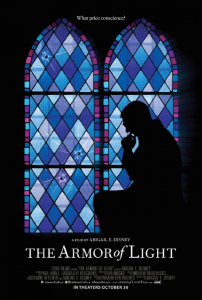

Religion is No Silver Bullet for Gun Violence: The Armor of Light Film Review

A humanist and an anti-abortion activist walk into a bar…Sounds like the start of a joke, but Abigail Disney’s documentary, The Armor of Light, touches on the shared values of humanists and one anti-abortion protestor, Rev. Rob Schenck, who has expanded his definition of the term “pro-life” to include protesting gun violence. Though the term “pro-life” frequently makes the abortion rights-advocating feminist in me cringe, mostly because so-called “pro-life” protestors seem to have no regard for the lives of women who need abortions, Schenk sees the term as a directive to protect human life from conception until natural death. However, despite my many disagreements with Schenck, by the end of the film I found myself wondering if humanists and Christians might be able to work together in order to bring about a more peaceful society, at least in regard to gun control.

The film begins with a brief overview of Schenck’s activism on behalf of the anti-abortion movement, including his work with the extremist group Operation Rescue, which attempts to shut down women’s healthcare clinics. (One such struggle took place in 1992 in Buffalo, New York, near the American Humanist Association’s offices at the time, and then-editor of the Humanist magazine Rick Szykowny dedicated an entire issue to the conflict.) However, Schenck’s narration suggests that he became disillusioned with the violence against abortion providers that Operation Rescue encouraged, so he founded Faith and Action, described on its website as “America’s only Christian outreach to top-level government officials in Washington, DC…Our purpose is affect [sic] the hearts and minds of America’s public policy makers with Christ’s mandate in the two Great Commandments: Love God With All Your Heart, Soul, Mind and Strength, and Love Your Neighbor As Yourself.” (This blurring of what should be a solid line separating church and state will likely not endear Schenck to humanist viewers.)

Fortunately, Schenck’s story is not the only one featured in the film. The Armor of Light also follows Lucy McBath, who became an outspoken supporter for gun control after her unarmed teenage son Jordan Davis was shot and killed in 2012 by a man who objected to the music Jordan was playing in his SUV. McBath tearfully recounts the moment when she learned that Jordan was in the hospital and passionately explains her wish that no parent should ever have to experience such heartbreaking tragedy. Though she mentions her Christian faith in passing, McBath is primarily portrayed as a grieving mother fighting to prevent future gun violence, making her much more likely to garner the sympathy of non-Christian viewers.

Schenck and McBath’s paths intersect when Schenk invites her to the headquarters of Faith and Action, where he confesses to her that he would like to incorporate gun control into his organization’s “pro-life” platform. However, Schenck is hesitant to openly adopt an anti-gun platform because so many evangelical Christians favor policies that allow Americans to easily purchase firearms. (I am baffled by the producer’s decision to pair the section of the film where Schenck identifies evangelical Christians and Tea Party Republicans as his community with a soundtrack of atheist and feminist Ani DiFranco’s secularized version of the hymn “Amazing Grace.”) McBath, however, finally gives Schenck the courage to speak out against gun violence, and the rest of the film follows him in his quest to convince other evangelical Christians to consider his views.

While I found Schenck’s earnest appeals to the “beauty of humanity” and the paramount importance of human life to be compelling—almost humanistic at times—I couldn’t help but feel as though his attempts to sway his fellow evangelical pastors missed the mark. Christian leaders in the film frequently defend their views about guns, whether for or against, by quoting scripture. However, I suspect that analyses of race, class, and gender would have much more than the Bible to say about why Americans insist on clinging to their guns, despite the high rates of fatalities they cause. (CNN recently reported that in 2013 alone, 406,496 Americans died from gun violence.) For instance, while the documentary touches on the role race plays in attitudes toward gun control—Schenck’s visit to a black church where parishioners discuss their opposition to guns is paired with Schenck’s attendance at a meeting of white, male pastors in Ohio who are adamantly in favor of guns—it does not delve deeply into the racist undertones of ideas perpetuated by the gun lobby and touted by many white individuals clinging to their right to bear arms. All of the events that Schenck attends, including a National Rifle Association (NRA) convention, are dominated by white, evangelical Christians who justify their need for guns by referring to vague threats from some spectral Other who may, at any time, break into their homes, kidnap their children, and assault their wives. Though none of the interviewees specifically mention race, I couldn’t help but wonder if they were engaging in what law professor Ian Haney López refers to as “dog whistle racism.” In his book, Dog Whistle Politics, López defines dog whistle racism as coded appeals to racial stereotypes that, without explicitly mentioning race, tap into middle and working class whites’ perception that “the challenges in their lives stem from the increasing presence of nonwhites.” Despite the many strides that US culture has made toward racial equality, we are still plagued by inaccurate and damaging representations of young black men as dangerous thugs, and this stereotype was almost certainly a factor in Jordan Davis’s death.

The need to always be ready to defend one’s self, without relying on assistance from the police or other public services, a view espoused by evangelical Christians afraid of having their guns taken away, also seems to play into a class-based “culture of honor,” described by sociology professor Jay Livingston as social status based upon public opinion and personal reputation that arises “where the state is weak or is concerned with justice only for some (the elite).” A culture of honor demands that individuals, particularly men, rely on their own devices to defend themselves, their families, and their honor—which is their reputation as self-sufficient and masculine. Given the rural, working-class backgrounds of the pastors in Ohio featured in the documentary, I could see how they might feel as though they were on their own and that protecting their families was up to them. But nowhere else in the documentary is this view brought into such sharp focus than in a meeting of four anti-abortion leaders, including Schenck, all of whom are white men. Ignoring Schenk’s plea to reconsider their stances on gun rights, the other leaders angrily appeal to their need for independence from “the nanny state” for protection. Their defense of owning guns has little to do with their religion and much more to do with their perception of themselves as self-sufficient, masculine men. Though The Armor of Light ends with McBath’s vow to continue her activism and Schenck’s plea for evangelicals to put their faith in God’s protection and not in guns, I suspect that Schenk has a lot more work ahead of him if he wants to win over his fellow conservative Christians.

I left the film feeling optimistic that humanists might be able to work with people like Schenck in order to enforce better gun control in the US through mandatory waiting periods, thorough background checks, and other measures to monitor the sale and use of firearms. Schenck’s views on abortion and church-state separation sharply contrast with the opinions of many humanists, but individuals in the humanist community may still sympathize with his earnest desire to bring about a more peaceful, just society. Having reflected on the film, however, I can’t help but wonder if appeals to religion miss the mark in attempting to convince evangelical Christians to lay down their guns. The individuals in the film who defended their ownership and use of guns did so not based on the Bible but on larger cultural ideas about race, class and gender. These ideas, particularly the insistence of rigid gender roles for men, are frequently perpetuated by evangelical Christianity. If Schenck wants to change people’s hearts and minds on gun issues, he’s going to need to also work to change their minds about bigger ideas as well. His message may find a mark in some humanist allies, but I suspect it may also bounce off many evangelical Christians it was intending to hit.