The Revolution Will Not Be Televised: Black Panther, Afrofuturism, and Liberation Politics

Black Panther is a cinematic masterpiece, flaws and all

Black Panther is a cinematic masterpiece, flaws and all Imagine an alternative reality in which a sliver of Africa never experienced the ravages of white supremacy and colonialism. That land is Wakanda, and T’Challa—the Black Panther—is the warrior king of Wakanda.

That is how I explained Black Panther to my father, someone who has always been incurious when it comes to superhero movies. After having clarified that the film wasn’t about the Black Panther Party (to my father’s dismay), I knew that appealing to his awareness of underlying causes for global systemic injustices would spark interest. I was right. Not only did he go to see Black Panther with me (my fourth viewing) and my son (his second viewing), afterwards he went so far as to say that writer-director Ryan Coogler’s record-shattering big screen juggernaut was “great.”

Black Panther is great, and for so many reasons. However, along with this greatness come faults that cannot be overlooked. First, a brief overview of the Black Panther story:

Following his father’s death in a terrorist attack, Wakandan prince T’Challa (played by Chadwick Boseman) returns home to assume the mantle of king. A chain of events soon unfold that test T’Challa’s responsibilities as king and his abilities as the superhero Black Panther. The fate of his kingship, the nation of Wakanda, and the entire world are jeopardized as T’Challa is forced to contend with N’Jadaka, aka Erik Killmonger (Michael B. Jordan), an adversary that embodies the sins of his father.

Since this is mainly a non-spoiler review, I will highlight the “good” and the “bad” of Black Panther in two parts: The Love and The Disappointment.

The Love

(Note: This contains no spoilers)

It’s been hard to miss the hype and overwhelming critical praise surrounding Black Panther a week or so before its release. This is one of those rare situations where it’s safe to believe the hype. Here’s why:

Authentic vibes. This is a shout out to the non-sentient characters. This film’s locations, costumes, and language added to the living, breathing aesthetic in noticeable ways.

Brilliant Afrofuturism. The ambitions and possibilities featured in Black Panther is cinematic Afrofuturism. It wasn’t until more recently that I familiarized myself with Afrofuturism, and I like how The Root attempts to describe what is more fluid than static when it comes to genre elements.

Afrofuturism is not black sci-fi. It’s not black fantasy. It’s not an easily definable artistic genre but, rather, a sweeping, cultural aesthetic that examines issues around black representation, the black future and black agency using music, novels, visual media, history and myth to create something else entirely.

Wakanda is a technological wonderland thanks to a cosmic substance known as vibranium. However, the glowing yet understated beauty of Black Panther’s Afrofuturist narrative relies on what I mentioned to my father: Wakanda exists in an alternative reality where systems shaped by white supremacy and colonialism have never sullied Wakandan soil.

In Wakanda, we are able to catch a glimpse of what Black wellbeing and prosperity would be like were it not shackled by social, economic, and political deprivations initiated by the violent legacy of capitalism, anti-black racism, and imperialism.

In Wakanda, women shamelessly rock armpit hair because they aren’t burdened by the absurd demands of colonized patriarchal social norms.

In Wakanda, there is no need for protests to force a world that hates us to listen to us.

In Wakanda, there is no need for devising political actions to engage a political process that was designed and is maintained to work against us.

In Wakanda, Sandra Bland and Philando Castile and Tamir Rice and Kathryn Johnston and countless others unjustly taken from us are safe, whole, and living their best lives.

In Wakanda, Black lives matter and there’s no need for hashtags or think pieces or protests or educational documentaries or ongoing dialogues to suss out what is already a foregone conclusion.

The glory of Black women done right.

The glory of Black women done right.

If there is one thing everyone who has seen this film can agree on, it’s that the Black female characters are its backbone—particularly Wakandan spy and T’Challa’s former lover Nakia (played by Lupita Nyong’o), teen genius and T’Challa’s sister Shuri (Letitia Wright), and my favorite character, head of Wakandan armed forces and intel Okoye (Danai Gurira). The ingenuity, leadership, might, grace, wisdom, and charisma of these women shines like a gamma-ray burst.

In 5 ways that ‘Black Panther’ celebrates and elevates black women, USA Today’s Anika Reed fleshes out this aspect of the film.

One movie isn’t going to eradicate racism, or fix gender or racial issues in America, but it’s a step in the right direction. Representation in pop culture matters, and the women of Black Panther are celebrated and validated throughout the film in powerful ways.

It seemed fitting that T’Chaka, T’Challa’s father, provided his son with only a single piece of insight on how to best rule Wakanda—to surround himself with people he trusts.

As the story unfolds, it’s clear that these women are precisely the support system T’Challa needs. But what Black Panther gets right is the fact that these women don’t exist as mere objectified mechanisms to mindlessly appease the whims of T’Challa or the Wakandan throne. Instead, they are intelligent, complex beings with agency who inhabit diverging roles that just happen to compliment T’Challa’s vision for Wakanda’s future.

And if that weren’t the case, if T’Challa ever deviated from that vision and took it to a dark place that didn’t serve the people, then in order to save the country, they wouldn’t hesitate to put him down—and I love that they possess (and display) the capacity to do just that if needed.

Bold, beautiful, unapologetic blackness. I knew that this film would have a Black ensemble cast and that the film would explore the African nation Wakanda, but I wasn’t ready for the concert of uncompromising blackness that gushed from the big screen. This movie was Black as hell, and I loved every melanated drop of it.

That distinct yet familiar dry wit and playful banter commonly shared among Black people. Specific non-verbal communications. The elaborate hairstyles. That unique self-confidence. The dancing and music. The deliberate reflection of the Pan-African flag colors in T’Challa, Nakia, and Okoye’s outfits.

Throughout, Coogler is able to weave together a layered story consistent with the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s mainstream thematic beats while also synthesizing an ongoing dialogue that connected directly with the real lived texture of Black culture and Black experiences. In this, Black Panther decenters the white gaze and provides a rare instance of a major motion picture’s storytelling being fashioned by and filtered through the Black critical analysis of social reality.

Black Panther doesn’t resonate with Black audiences because it just happens to assemble a majority Black cast; rather, it resonates because it’s a story told by us that regards the specific concerns and knowledge that is culturally relevant to Black communities.

In other words, Black Panther is for Black people. This doesn’t mean that it cannot be enjoyed by non-Black people. This just means that the ways in which this film operates on multiple levels is better understood by the general Black audience since the subtext interwoven into the story’s elements is communicated in a spoken and unspoken language acquired through navigating an anti-black world as a Black individual.

This brings to the forefront a significant aspect of representation. Here in the US, the list of all-white casts and crew involved in creating stories told by white people since the inception of entertainment mediums like television and film are endless.

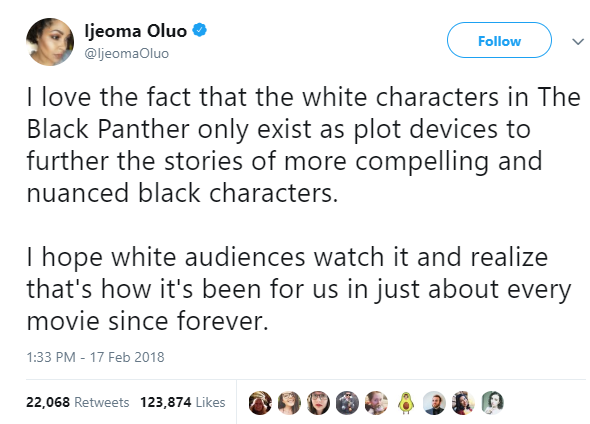

This is why, honestly, I’m not sure white people are able to fully appreciate the importance of representation since the normalized construct of our social reality has always centered them. All they have ever known is full representation. And it’s this truth that writer, activist, and 2018 Feminist Humanist Award recipient Ijeoma Oluo emphasizes in this comment regarding Black Panther.

Much like how Jordan Peele’s Get Out disregards the way our culture valorizes whiteness in order to prioritize messages that commune with the double consciousness of Black America, Black Panther does the same thing but in different ways within a different genre regarding different subject matters.

The Disappointment

There really is no such thing as a perfect movie. And since it’s possible to both adore something for what it is while also being mindful of what it isn’t, here are the three main problems that I had with this film.

Where are the Blackqueers? Representation in film is one way to challenge oppressive dominant stories. So it’s disappointing that Black Panther lacked explicit representation from the LGBTQ community, especially since the blueprint already existed in the more recent comic book runs of Ta-Nehisi Coates, Roxane Gay, and Yona Harvey.

When it comes to including more genuine depictions of Black perspectives and Black stories in cinema, this is a reminder that the value many ascribe to “representation” does not—or at least, should not—begin and end with just blackness.

There may be diverging ideas on what Afrofuturism entails, but a key aspect of this genre should be subverting the mutilated and restrictive nature of colonized conceptions of being and existence.

Isolationism to the point of ignoring global atrocities is unjustifiable. It’s logical that Wakanda would choose to isolate itself from a world plagued by greed, oppression, and war. Wanting to preserve the resources and harmony abundant in Wakanda is understandable, but to do this and not incorporate ways to prevent or end unfathomable horrors like slavery and genocide isn’t something that can be rationalized.

I understand that this isolationist stance is canon—I’m disappointed that Coogler didn’t find a way to at least have T’Challa and Wakanda’s tribe leaders address this subject in a more mindful way rather than simply parrot “interfering with the outside world is not our way” slogans.

No Wakanda for N’Jadaka.

(Note: this section includes spoilers regarding the antagonist’s depiction and plot)

The charisma and swagger of Michael B. Jordan as N’Jadaka works on so many different levels, which is why N’Jadaka is already being heralded by critics as one of Marvel’s greatest supervillains.

I appreciate certain facets of what N’Jadaka brings to the table. I appreciate how, technically, N’Jadaka is an anti-villain. I appreciate how his intentions, at least partly, are ambitions that many can sympathize with. I appreciate how in the first scene with this character, after a white artifact expert tells him the items in the exhibit aren’t for sale, he snaps at her:

“How do you think your ancestors got these? Do you think they paid a fair price? Or did they take it, like they took everything else?”

What?! Yes! This moment was met with whooping from the audience in almost all of my viewings.

While I not only understand N’Jadaka’s righteous indignation and agree with the essence of his motivations, he was flawed in ways that “make sense” given his villain status but also in ways that didn’t do the radical ideas he championed justice.

He embodied patriarchal violence, particularly misogynoiristic violence enacted against Black women. He displayed cruel irreverence for the Wakandan people, traditions, and resources. His pursuit of what he believes is just not only reproduced the brutal, morally bankrupt logic of his oppressors, it would have wrought destruction on Wakanda as well as countless innocents—including the lives of many oppressed people he intended to liberate.

I get it. He’s the villain. Even so, the hero succeeds against the villain at the expense of ineptly discarding an important truth N’Jadaka advances: we need radical change that topples global systems of oppression.

N’Jadaka is right for criticizing Wakandan isolationist policies that led to Wakanda standing idly by as centuries of evils have been carried out against global marginalized communities, including the Black diaspora in the US. He is right in wanting to reverse this tradition and to help oppressed people. Yes, his mission and ultimate goal (a new empire) is skewed. I love that the film delves into a discussion of revolution. I’m disappointed that said discussion is superficial and seemingly rejected as being “not the answer.”

We are left with a message that suggests N’Jadaka was irredeemable and that his vision to upend global tyranny is just “too much.” Instead, T’Challa’s “compromise” is to open an outreach center that won’t transform the systemic conditions that necessitate the need for an outreach center. This fits neatly with political ideologies that believe making improvements to an inherently oppressive system will solve the problems part and parcel to said inherently oppressive system—Band-Aids for mortal wounds.

I recognize that when it comes to liberation politics—the necessity of Black liberation and the global liberation of all oppressed people, the nuance of such radical ideas and strategies, the respect for the logic and lives of those who desire it—it’s not something that will be portrayed with appropriate care in a two-hour long Disney superhero film—a genre whose characters aren’t as complex and ambiguous as they are in real life or in dramas that attempt to depict realistic alternative realities.

Overall

As I exited the theater upon my first viewing, I observed a father exchange the Wakanda greeting (a cross-arm salute) with his young daughter and then give her a long, warm embrace.

Circling back to how I explained what this movie was about to my father, this moment between father and daughter perfectly reflects what this film represents in terms of how dramatically different the existence of the Black diaspora would be if the crush of white supremacy and colonialism were eliminated.

That is why this film makes so many of us emotional. It’s why I and countless others enthusiastically experienced multiple viewings over the weekend. It’s why we say that Black Panther is for us and about us.

I am able to rejoice in this film despite the blemishes in the fantasy. I treasure Black Panther and hope that audiences continue to pack the house to experience it.