A Visit to the New Vonnegut Library and Museum

Canonization can do irreparable harm to a person’s reputation. What got them notoriety in the first place was their willingness to fight for something, and therefore against something, but canonization requires being for everyone. And being for everyone means fighting for nothing—or at least for nothing anyone could object to. A moral filter gets applied to the canonized person’s life whereby the hue and saturation are adjusted to hide sharp edges and imperfect complexions. For example, Abraham Lincoln, the only US president to preside over a civil war, is now canonized as the patron saint of compromise and civility. True, he said a house divided cannot stand, but he also said slavery and freedom cannot stand together in the same house. Southerners knew what his election symbolized—that there would be no more compromise on slavery—and responded accordingly.

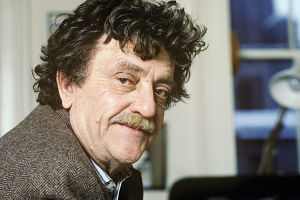

As Indianapolis has more and more celebrated Kurt Vonnegut, the playful novelist and sneakily sincere humanist, I was worried this moral filter would be applied to him. Vonnegut the person, a hater of war and lover of democratic freedom, would be replaced by Vonnegut the ideal, a sort of iced-tea drinking, “aw-shucks” uncle from the Midwest who just wants everybody to “get along.”

Thankfully, my visit to the recently re-opened Vonnegut Library and Museum put that worry to bed.

The Vonnegut Library and Museum first opened in 2011. The original location was too small and its storefront too inconspicuous though, and management had been looking to relocate for years. The museum’s lease ended this past January, and after some fundraising and house-hunting the new location was acquired—a 10,000-square-foot, three-story building in Indianapolis’s Historic District, just down the street from the Madam Walker Theatre and IUPUI college campus.

The museum officially opened in November, although it isn’t finished yet. The first story will eventually be an anti-censorship coffee shop with shelves of previously banned novels and table-top collages of newspaper stories on literary censorship. (Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five—based on his experience surviving the Allied bombing of Dresden during World War II—is now required reading for most high-schoolers but was, as you might expect, once banned by many school boards.) The second story will be for events and galleries, and the third story will be for exhibits. Right now, the third story exhibit is on Slaughterhouse-Five. The first glass case you see after getting off the elevator contains Vonnegut’s Purple Heart he “got for frost bite” as he liked to say and a Nazi sword he stole while in Germany. Lanci Miccio’s Slaughterhouse-Five-inspired oil paintings and Vonnegut-related paraphernalia (drawings, rejection letters, yearbooks, first edition copies, etc.) hang on the walls throughout the museum.

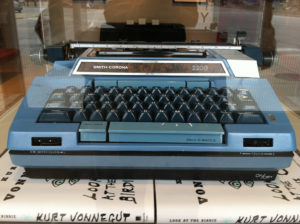

Kurt Vonnegut’s typewriter seen in Vonnegut Library and Museum’s original location (Photo by Dustin Batt via Flickr)

Vonnegut means a lot to Indianapolis. The best cocktails in the city are at a Vonnegut-themed cocktail bar, and one of the city’s three building-size murals are of him. He wasn’t ashamed of being from Indianapolis or Indiana or the Midwest. He didn’t think it was something he had to escape from. “All my jokes are Indianapolis,” he said. “All my attitudes are Indianapolis…What people like about me is Indianapolis.” He would say that any state that made socialist Eugene Debs must be a pretty damn good place. (A poster of Debs, who ran for president while in prison for opposing US entry into World War I, is already on the wall of the future anti-censorship coffee shop.)

Vonnegut, who for years served as the honorary president of the American Humanist Association, was a humanist in the best and truest sense. He cared both about human beings and about humanity and knew the reward for his love was the love itself. His social morality was simple: he was against war and for helping people. No ideological runaround could stop him from reaching the obvious: when someone is hungry, and there is food, they should be fed; when someone needs work, and there is work to do, they should be given work. What’s more, he truly understood the tragedies of life and was therefore neither sentimental nor bleak. One can see him now, walking across military lines after being forced to dig up the remains of human beings in Dresden, Nazi sword in hand, knowing one day he would be able to smile about having taken it.

Vonnegut was the kind of writer who could make himself laugh (or cry), and laughter is what I’ll always think of when I think about him. Laughter and smiling. Some laugh, others sneer. Some smile, others smirk. The former know that life is a joke played on us all; the latter try to think they alone are in on it. Vonnegut said that in times of happiness you ought to look around and say, “If this isn’t nice, I don’t know what is.” Spending time in the new Vonnegut museum is one of those moments.