Auctioning Responsibility: George Zimmerman and the Relics of American Whiteness

[Warning: This article includes disturbing images.]

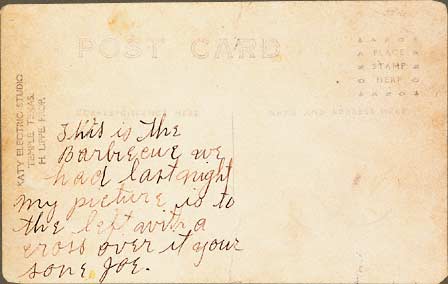

Image 22b. withoutsanctury.org, Image property of James Allen and John Littlefield.

This is the barbecue we had last night.

My picture is to the left with a cross over it.

—Your son, Joe (1916)

At first glance, these words above—taken from the back of a postcard—tell the story of a celebratory gathering, a barbecue, and a son who thought enough to commemorate the occasion with a photograph that would be shared with his parents. But Joe’s words aren’t from just any postcard. They’re found on the back of a lynching postcard and commemorate the murder of Jesse Washington, a black man hung from a utility pole in Robinson, Texas, on May 16, 1916. The “barbecue” attended by Joe was the brutal murder, mutilation, and burning of black flesh.

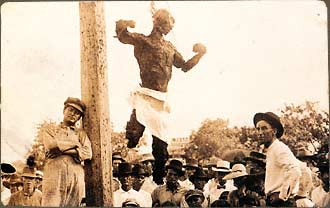

Image 22a. withoutsanctury.org, Image property of James Allen and John Littlefield.

Jesse Washington was murdered exactly 100 years ago today. Joe may have died a few generations ago. But honestly, how far have we come?

George Zimmerman is trying to sell the gun he used to take the life of Trayvon Martin. Zimmerman’s audacity left me shocked and dismayed. I am also trying to reconcile that in 2016, a shameful American pastime continues: the simultaneous obfuscation and celebration of white responsibility for racialized terror.

Many of us will surely continue to celebrate our “progress” on matters of race. Do we have any shame at all? Whose progress do “we” speak of when we talk about race? Much of what’s been cited as “black progress,” historically, obscures the reality that there isn’t much “black” about it. While much of the labor of “racial progress” has been, and continues to be, carried on the backs of the victims of racialized social difference, white talk of race progress is a sleight-of-hand tactic that trades out white culpability for a façade of black responsibility. As James Baldwin reminded us many years ago (and more recently, as comedian Chris Rock has), any progress struggled for indicates something of white movement away from who we have been. But Zimmerman reminds that despite our best efforts at innocence, many of us are still the same ol’ Joe.

Schizophrenic denial/celebration of responsibility continues in 2016, animated in easy and unrepentant efforts to auction off blame, where tools of continued black death become iconic on sites of commemorative profit making. Such tendencies don’t just exist at an individual level, but are also alive and well-embedded within “great” American institutions; structures and economies built by free labor, built by the backs of its racial others. As if the burden of proof isn’t already saturated with the tragic evidence ensuring (and insuring against) responsibility, consider this: almost twenty years after the murder of Nicole Brown, a very white constituency is still working to prove O.J.’s involvement, even to the extent of attempting evidentiary testing of an old rusty knife found buried in Simpson’s backyard almost fifteen years ago.

Zimmerman’s desperation, our white incredulity, and the potential demand for this contemporary relic of America’s living history are, sadly, neither surprising nor new. The Obama election was to usher in a season of change and “great racial progress.” Instead, today marks the 100-year anniversary of Washington’s murder, the departure of America’s first black president, and Zimmerman still trying to profit off of a murder for which he was not even convicted.

Tragically, this is but another chapter of the book that bears witness to the durable demagogue—the religion of whiteness, and its apostate child, American racism. Make no mistake about it: American whiteness is a growing American religion. Like many religions, its most cherished and sacred ritual is the relentless crucifixion of black bodies, and the continued sanctification of white communion through the celebration of blood-soaked relics.

“Racism is a faith,” wrote theologian George D. Kelsey in 1965, “a form of idolatry.” Kelsey was one of the first to explore racism and white supremacy as an, ostensibly, theological problem—a skewed, “abortive” effort to make meaning for oneself or community through derision and the dehumanization of others.

Like any faith, theology, or religious tradition, this white religion in America brought with it a variety of offerings, rituals, and communal activities designed to reinforce notions of white security and superiority. The central ritual of this white religion was lynching, the extra-judicial killing of (mostly) African Americans through vigilante “justice.” From about 1870-1970, around 5,000 lynchings occurred in the United States and between 70-80 percent of these victims were African Americans.

But the ritual activity of white religion didn’t stop with these “sacrifices.” Some of the more vicious and gut-wrenching aspects of these murders were the tokens and souvenirs collected from dead (and dying) black bodies. Hair was taken and skin was flayed. Many whites, including children, took home these trinkets as reminders of the black sacrificial offering having temporarily secured a sense of fixity and order for the lynch mob and the white society its defender. Similar in their functional effect to more traditionally recognized religious artifacts such as Bibles or baptismal water, these “mementos of black bodies,” as scholar of African American religion Anthony B. Pinn describes them, “took on a transcendent quality” for adherents to white religion. “Transfigured into powerful symbols,” Pinn argues, the relics garnered in such ritualistic activities had the ironic effect of “turning the former objects of history into shapers of history.” Moreover, lynchings took on the character of religious pilgrimage in that many citizens would travel long distances to take part in the spectacle offered by the murder, secure a trinket or memento of white innocence, if not to partake more viscerally in the actual killing.

For a bit more context, and in no particular order, here are some examples of this so-called white religion’s divine relics:

- Lynching postcards

- Magical incantations; sacred racecraft

- Murder weapons

- Commemorative autographs of murderers

- Fingers from lynch victims; skulls of “Japs” sent home during WWII

- Abraham Lincoln assassination memorabilia

- “Antique” segregation signs

- Replicas of “Fat Man,” the bomb dropped on Nagasaki (National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio), “Little Boy,” the bomb dropped on Hiroshima, and Enola Gay, the B-29 used to drop the bomb (both at the Smithsonian); together, these white religious relics are responsible for over 100,000 deaths.

- Drones like the MQ-1L Predator on full tilt in the Smithsonian

- The Confederate flag (It’s no longer available for purchase at Wal-Mart, a response to the 2015 church massacre in Charleston, South Carolina. The decision so incensed one white man from Tupelo, Mississippi, he decided to bomb his local Wal-Mart. (Note: One tragic irony of Wal-Mart’s ban on sacred white memorabilia is that guns are still sold in their stores across the United States.)

These tokens of history work to solidify the identities of white and black in a mutually exclusive yet symbiotic fashion, even where lynchings and violence has not been experienced directly. Theologian James Cone situates the effects of lynching on black identity formation by recalling the autobiographical account of Richard Wright, who said, “I had never in my life been abused by whites, but I had already become conditioned to their existence as though I had been the victim of a thousand lynchings.” Wright’s words not only connect black and white identity to each other, but also situate the practice of lynching, and the commemoration of racialized murder, as instrumental to white religion in practice.

Our violence is only trumped by a deeper, more creeping recognition that no matter how many people we kill, or how many killers we commemorate, our murderous efforts at safety will not ensure our future.

Pick your poison, tell me what you doing

Everybody gon’ respect the shooter

But the one in front of the gun lives forever

—Kendrick Lamar, “Money Trees” (2012)

Further Reading:

James H. Cone, The Cross and the Lynching Tree (Orbis Books, 2013).

Christopher M. Driscoll, White Lies: Race and Uncertainty in the Twilight of American Religion (Routledge, 2015).

Kristina DuRocher, Raising Racists: The Socialization of White Children in the Jim Crow South (University Press of Kentucky, 2011).

Karen E. Fields, Barbara J. Fields, Racecraft: The Soul of Inequality in American Life (Verso Books, 2014)

George D. Kelsey, Racism and the Christian Understanding of Man: An Analysis and Criticism of Racism as an Idolatrous Religion (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1965).

Anthony B. Pinn, Terror and Triumph: The Nature of Black Religion (Fortress Press, 2003).

Harvey Young, “The Black Body as Souvenir in American Lynching,” Theatre Journal 57 (2005) 639 – 657. Johns Hopkins University Press.