The Dangers of Patriotism: Remembering Robert Prager

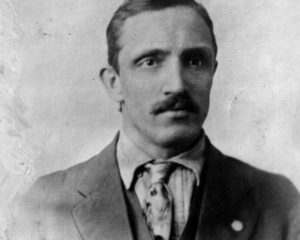

Robert Prager

Robert Prager The love affair between patriotism and the military was always going to be unavoidable in 2018. As we approach the centenary of the 1918 armistice, countries around the world will soon be commemorating the end of the First World War with that familiar but curious mix of bombast and solemnity. Preparations are already underway in Australia and New Zealand for the Anzac Day marches. In the United States, it looks like President Donald Trump’s game of soldiers—sorry, military parade—is scheduled for Veterans’ Day. And in the United Kingdom, where I live, you can already find early blooms of the remembrance poppy, something not normally seen flowering until late October.

Amid all the inevitable flags and pomp, there’s one incident that is unlikely to be remembered. Its obscurity is our loss, for the events of April 4, 1918, should make us look at the patriotic nature of remembrance—and, indeed, politics itself—in a much more critical light. As humanists, it is time for us to acknowledge the dangers of patriotism.

This year, the fourth of April marks the hundredth anniversary of the killing of Robert Prager, the only US citizen whose death is officially recorded as “patriotic murder.” Prager emigrated to the USA from his native Germany at the age of seventeen, eventually settling in the small mining town of Collinsville, Illinois. Following the United States’ entry into World War I, he and many other German Americans became the victims of increasingly hostile accusations of treachery and espionage. President Woodrow Wilson added to the toxic atmosphere when he spoke of Americans “born under foreign flags…who have poured the poison of disloyalty into the very arteries of our national life.“ Wilson concluded his tirade ominously: “such creatures of passion, disloyalty and anarchy must be crushed out.”

Matters came to a head in Collinsville one Thursday evening, when Prager was assailed by a flag-wielding mob around three hundred-strong and forced to parade barefoot through town. The Stars and Stripes was draped over his head as he was repeatedly made to sing patriotic anthems and swear his allegiance to the US. As the night wore on, the cavalcade made its way to a hackberry tree on the edge of town. Prager’s hands were bound with a handkerchief, a noose was slipped over his head, and he was hauled into the night air. As his neck broke, the crowd gave three cheers for the red, white, and blue.

Perhaps more astonishing than the lynching itself is the trial that followed. The eleven men eventually charged with his murder arrived in court waving US flags and wearing red, white, and blue ribbons on their lapels. Throughout the hearings they stressed their patriotic credentials, arguing that Prager’s ordeal and death were simply an expression of national pride—hence the term “patriotic murder.” The jury agreed, and the eleven defendants were cleared of all charges.

Of course, Prager’s death is remarkable because it was so unusual. Most self-professed patriots do not spend their Thursday evenings lynching their neighbors. Nor should we overlook the obvious strains of xenophobia in this tragic event. But this doesn’t mean we can absolve patriotism of any wrongdoing. Had the sick pantomime in Collinsville been the result of religious fanaticism, you can be sure that humanists would have plenty to say about the blind devotion, cruel intolerance, and moral hazards religion breeds. So let’s not be shy about condemning national fanaticism when the consequences are exactly the same.

Yes, the killing of Robert Prager was an extreme case of patriotic expression, but it is often the extreme cases that force us to confront issues we’ve long ignored. As humanists who would like to see a more rational, compassionate world, we must confront the dangers of patriotism—the blind devotion, the cruel intolerance, and moral hazards.

If you’ve ever attended a remembrance service, you could be forgiven for thinking there’s nothing wrong with national devotion. Whatever your nationality, allegiance to the nation is routinely raised up as “a pious and honorable duty,” one of the noblest convictions in military, political, and civic life. In the many armistice commemorations this year we’ll be encouraged to honor and idolize the patriotic devotion of others, even when it sent them to their death.

It’s all too easy to forget the dark side of devotion. Writing during the First World War, the author Rabindranath Tagore described the nation as “one of the most powerful anaesthetics that man has invented.” One hundred years later the observation is still true: when governments seek to numb dissent and debate, it’s to patriotism they invariably turn. In India the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party has warned that “anti-national” criticism of its government will not be covered by freedom of expression. In the UK the leader of the House of Commons has accused broadcasters of being unpatriotic in criticizing the country’s shambolic Brexit proceedings—a sentiment echoed by White House spokesperson Kellyanne Conway, who dismissed criticism of Trump as “neither productive nor patriotic.” The president himself, with a flair for demagogy that is somehow both pathetic and terrifying, told supporters after his State of the Union speech that anyone who refused to applaud him was “un-American” and “treasonous.”

Such is the sedative power of patriotism that governments will go to great lengths to manufacture. I use the word manufacture advisedly: human beings do not instinctively fall in love with millions of compatriots they’ll never meet or vast stretches of land they’ll never know. That kind of affection can only be taught. And so governments spend millions of dollars manufacturing national allegiance, whether it’s in the classroom, through military service, or with public events like remembrance services. China and Russia are currently at the forefront of this endeavor, smothering their citizens with obligatory “patriotic education” programs that replace intellectual freedom with an unquestioning loyalty to the state.

All this creates an intolerant and hostile environment in which the apparent crime of being unpatriotic becomes loaded with such opprobrium that politicians must endlessly prove how much they love their country, whether by singing the national anthem, wearing a remembrance poppy or—as the Democrats learned the hard way in 2016—adorning their stages with flags. Even ordinary citizens aren’t safe: under a bill proposed by the Philippines government last year, anyone found not singing their country’s anthem “with fervor” could face up to one year in prison. Needless to say, this national kowtowing not only wastes a lot of time and energy that could be better spent elsewhere, but presents a serious challenge to the humanist ideals of tolerance and intellectual and expressive freedom.

One response to these concerns is to try and find a healthy, positive patriotism compatible with a humanist outlook. We are urged to look to the national pride of Martin Luther King Jr., not Donald Trump; Mahatma Gandhi over the Bharatiya Janata Party. Stories like Prager’s can be dismissed as ugly exceptions that fail to reflect the benign patriotism of most people.

I don’t deny that patriotism can be harmless or even inspire us to do good. But then so can a lot of things. King and Gandhi were also motivated by their deep religious convictions, but I doubt that would convert many humanists to Christianity or Hinduism. Just because something can inspire good doesn’t mean that it is an inherently good thing; nor, for that matter, does it mean that the good it inspires outweighs the bad.

But there’s a deeper problem with this approach. Patriotism, it is important to remember, is not a philosophy or a political ideology, but a feeling. It is a belief that our country and compatriots are more deserving of our favor than all other countries and people, and nothing more. As a result, it has nothing to say on matters of reason or morality, beyond the depressing idea that foreigners are somehow less deserving of our compassion than compatriots. Patriotism is, essentially, a morally empty phenomenon. As the economist Thorstein Veblen wrote, only a year before Prager’s death: “there is, indeed, nothing to hinder a bad citizen from being a good patriot; nor does it follow that a good citizen—in other respects—may not be a very indifferent patriot.’

All this means that we are unable to separate national pride into good and bad, patriotic and nationalistic. There is simply no moral justification for doing so. As much as it might sooth our consciences to say that Trump isn’t a “true” patriot, or that Prager’s murderers were chauvinists rather than patriots, we really have no basis to do so beyond our own discomfort at the thought of sharing a deep-seated belief with these people. Prager’s death really was patriotic murder, whether we like it or not.

Ultimately, this means that patriotism and humanism make for very awkward bedfellows. Frankly, it beggars belief that any humanist claiming to want a rational, compassionate, and peaceful world could also be a patriot. Not only is patriotism an irrational feeling based on an accident of birth—does it not seem suspicious that no one is ever a patriot of a country other than their own? Not only is patriotism used to justify and celebrate human rights abuses, as the flag-waving rhetoric surrounding the Patriot Act ably demonstrates. Not only does it entrench the morally arbitrary divisions of nationality, encouraging a parochial selfishness that routinely foils attempts at international cooperation, whether on issues of law, trade, or the environment. On top of all this: patriotism kills. And not just on the battlefield. Robert Prager was one victim; the British politician Jo Cox was another, gunned down and stabbed in 2016 by a man shouting “Britain first!” The murders of Ricky Best and Taliesin Namkai-Meche in Oregon last year were both justified by the culprit as an act of patriotism.

This is why, as a humanist, I am deeply uncomfortable with the patriotic nature of remembrance and politics in general. The tragedy of war should make us reflect on the conflict and division patriotism fuels, not bloat our national pride with tales of “our” brave soldiers.