Honoring the “Dregs,” America’s True Founding Fathers

Why we have teenagers, immigrants, convicts, minorities, and the unemployed to thank for our freedom

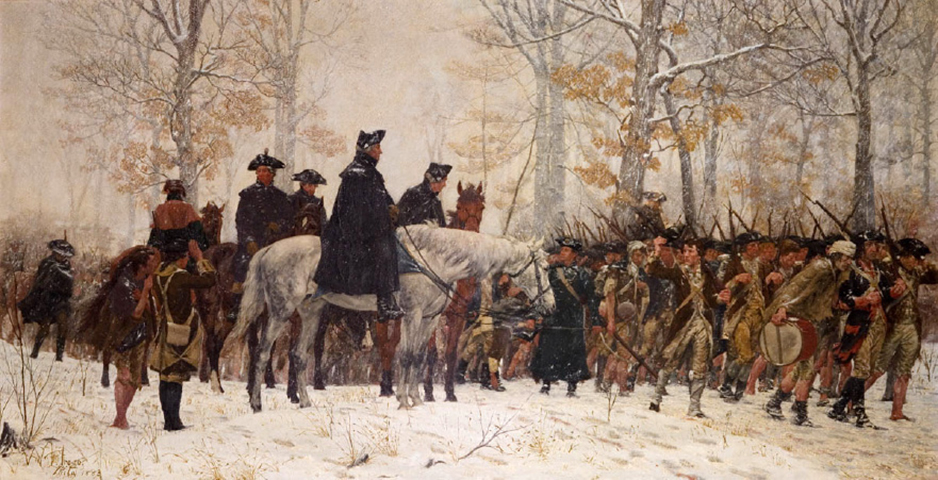

“The March to Valley Forge” (painting by William Trego, 1883)

“The March to Valley Forge” (painting by William Trego, 1883)

We’ve all but deified our founding fathers. Nearly to a man, they were well educated and from the upper strata of society, refined gentlemen of eloquence and means. They were full of contradictions that bordered on outright hypocrisy, yet still, their poignant words are invoked frequently today and their foresight seems almost prophetic. But stirring rhetoric could only take a revolution so far—someone still had to shoulder the burden and do the bleeding.

Some of those who did that bleeding were spurred by those poetic words, but they were few in number and tended to lose their zeal for revolution quickly once the miserable reality of prolonged warfare set in. The ones who endured the hardship for the duration, and thus founded our country, weren’t the men with their wigs and feathered pens, or even the mercantile professionals in their cozy cottages. They weren’t stirred by the fervor of a new country, but rather by desperation, coercion, or by the promise to be freed from the bondage held over them, not from the British but from their American masters donning in their wigs, issuing their eloquent words.

We romanticize the soldiers who inspired our Second Amendment, the middle-class citizen militias composed of merchants, farmers, teachers, and the like, but the militias proved all but worthless. They were soft and undisciplined, too used to warm beds and full bellies, too used to shod feet, attentive wives, and having people listen to them when they spoke. They had too much to lose to take the risks and endure the suffering that the task of gaining freedom required. Win or lose they had a home, whether they were ruled from across the Atlantic or by a Virginia planter class. They were the enfranchised.

We needed those who had virtually nothing to lose, not a material thing in this world to their name, nor a voice to complain about it. For the words of our great pantheon of founders to live on, they needed expendables who not only wouldn’t be missed, but that colonial society was all too eager to rid itself of, or as one gentleman from Virginia put it, they should look for “those lazy fellows who lurk about and are pests to society.” They are the ones who formed our Continental Army.

As a whole, they suffered more than any other American army ever has. They suffered a higher casualty rate on the battlefield than our Civil War armies and a far higher percentage died of disease in camp. Those who were captured rotted on British prison ships for our freedom. Two-thirds of those captured died—10,000 men—more than would die in battle. The British offered freedom to those who would serve in their navy, however the vast majority refused and continued to patriotically suffer for those men in wigs, who could pen words but not feed those who’d fought and been captured.

We all remember the fabled harsh winter in Valley Forge, but that wasn’t even the worst winter, either in conditions or in sickness and death. That would come three years after Valley Forge in 1780, as the army holed up in Morristown, New Jersey. That winter the men ate boiled tree bark to survive. A large part of the reason those men suffered so greatly was because the eloquent men in wigs failed to supply them properly. The unwanted dregs of society ate tree bark and died for us while the men whom we remember and revere were served hot meals next to warm fires by their slaves throughout that winter. Those dregs suffered through seven such winters.

The class of men who actually earned us our freedom were unwanted, slandered, and derided just as much then as they are now. As George Washington rode down the ranks, inspecting his soldiers, he would have peered down on the faces of teenagers, immigrants, convicts, blacks, and the impoverished unemployed. When the draft started the men with means would pay those in debtor’s prison to take their place in the army. They would pay constables to fill the ranks with vagrants and petty criminals who’d been arrested. Some men made fortunes searching out desperate souls willing to auction their lives away to escape debt, starvation, prison, or slavery, and then selling their service to those with the means to pay.

For eight long years our unwanted but newly indispensable dregs endured far more defeats than victories. They marched to survive another day far more often than they did in pursuit of a bested enemy. But they held on, because that’s what they had done their whole miserable lives—held on. For them victory and freedom wasn’t some abstract concept of determinism, it was a tangible hope, a plot of ground they could bury their hands in or a mule they could harness. It was having the right to say no to another man or to determine what time of day to take their meal or rest their bones.

Most had never held a gun before enlisting, but by the end of the war our expendables were the match for the greatest army the world had ever known, which by the way happened to be composed of Britain’s expendables as well.

If you can look at a carpenter, a tax collector, or a fisherman and tell your son or daughter to respect them because our savior and his disciples came from those professions, then you should also look at teenagers, immigrants, minorities, and those who are incarcerated with such reverence, because men just like them were our true founding fathers.