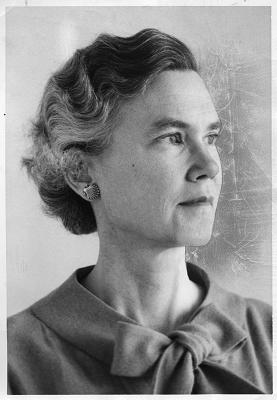

Humanist Women in History: Priscilla Robertson

March is Women’s History Month in the United States, the UK, and Australia. In commemoration we bring you the third of our five-part series: “Humanist Women in History.” The first installment profiled Shirley Chisholm and the second Frances Fox Piven.

“The first thing I desire for my children is a kind of openness to experience. I hardly know whether to call this openness the ability to love or the ability to perceive truth, for it is both.”

—Priscilla Robertson

Priscilla Robertson was born Priscilla Smith in Paris, France, in 1910. Her father, Preserved Smith, was a historian, and her mother was, in Robertson’s words, a “cheerful Christian” who died when her daughter was just three years old. Robertson’s father then raised Priscilla without any religion (his own father was a biblical scholar tried for heresy in 1892) and built a house for them in New England where she grew up.

In 1930 Robertson graduated from Vassar College, where her research focused on nineteenth-century history and the history of women and family life. She then worked as an organizer with the Southern Tenant Farmer’s Association. Later she was the literary editor of the Louisville Courier-Journal, where her husband, Cary Robertson, was the long-time Sunday editor. They had three children and lived on a farm raising beef and tobacco in Kentucky. During this time she published Lewis Farm: A New England Saga (1950) and Revolutions of 1848: A Social History (1952), which the New York Times described as “in the best tradition of what, in a word perhaps significantly beginning to be overworked, we must call humanism.” She also helped found the Kentucky Humanities Council and the Kentucky League of Women Voters.

After serving for two years as an associate editor at the Humanist magazine, Robertson took over the editorship in 1956. In her introductory column as editor in the May/June issue, Robertson pledged that the magazine would “work at a small part of the huge task of turning knowledge into wisdom.” During her tenure she published work by Nobel laureate H. J. Muller, psychologist Abraham Maslow, and science fiction writers Miriam Allen deFord and Isaac Asimov. She herself contributed numerous reviews and articles, including a series on the relationship between science and values. Writing on that subject in a 1952 Harper’s magazine piece titled, “What Shall I Tell My Children?” Robertson wrote:

True, it is harder to be a good person that a good scientist—there can be a carry-over from the laboratory but it is not automatic; hence the common remark that scientific judgment is no good in human affairs. But the discipline in either case consists in so great a willingness to let truth be true, and people be people, that you are willing to fight for this autonomy.

In March 1959 Robertson was dismissed by the board of directors of the American Humanist Association. According to Warren Allen Smith, the Humanist’s book editor at the time, the dismissal stemmed from an editorial disagreement over rushing the publication of an article by Corliss Lamont. As a consequence the magazine’s staff (who were mostly volunteers) resigned in a show of support.

Robertson went on to teach at Indiana University (Bloomington and Jeffersonville campuses) as well as at Harvard and two (now defunct) schools, the Louisville School of Art and Kentucky Southern College. In 1982 she published An Experience of Women: Pattern and Change in Nineteenth-Century Europe.

Priscilla Robertson died of a stroke on November 26, 1989, in Louisville, Kentucky, at the age of seventy-nine.