Humanly Possible: The Urgent Need to Increase Organ Donation Rates

Read Matthew Bulger’s rebuttal arguing in favor of using animals for human organ donation here.

There is no doubt—organ transplants save lives. In 2015 doctors in the US performed 30,000 transplants using organs from 14,500 donors (living and deceased). Although commendable, that number runs short of the over 120,000 people who are currently on the waitlist to receive organs, and studies indicate that 8,000 people die every year because they never made it to the top of the waitlist.

Unfortunately, this is the grim reality within the United States, where the need for organs gravely surpasses the number of donors. As of 2014 only 45 percent of Americans were registered organ donors. (Interestingly, in New York only 12.7 percent of residents were registered.)

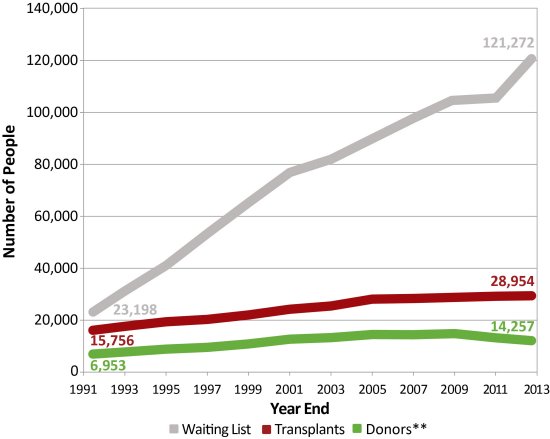

According to this graph provided by the US Department of Health and Human Services, the gap between individuals in need of organs and those who donate increases each year. And although the population is increasing, the number of donors has remained nearly the same over the past ten years. Why aren’t more Americans registered organ donors?

Instead of addressing the nation’s disconnect from this issue, researchers from the University of California want to redirect the problem onto another species. The UC Davis team’s latest undertaking involves forcing pig embryos to grow organs with human tissue instead of their own. The researchers hope that they will eventually reach a point in their research where once the pigs reach adulthood, they will be killed and their organs harvested for human use.

This research, currently in the early stages (embryos are only allowed to develop to day twenty eight, at which time they’re taken out of their mother and dissected for research), is very controversial. The National Institutes of Health issued a moratorium on funding such experiments last September, but the scientists have continued with funding from private donations.

At this point, much is unclear about the efficacy of injecting human stem cells into pig embryos, including whether the research will even produce the intended results. Although the goal is to grow human-like organs, there’s no way of knowing where the human stem cells will go once injected into the embryos. Some ethicists even voice concern over the possibility of the stem cells contributing to brain and/or reproductive development. If this is the case, we will be forced to seriously consider what it means to be human and reconcile our findings with our medical ethics. This research is still in the very early stages, and, considering that it lacks major government funding, is likely to move slowly.

Alternative measures to address the organ shortage may be met through the lab, but without the unethical use of other beings. Organs grown in petri dishes have found success. In this case, DNA is taken directly from the person in need of the organ, so transfer complications are minimal. Another alternative is 3D printing. Researchers have already successfully reproduced a number of body parts, but are still working on solid organs. These alternatives seem more likely, as the Department of Defense just yesterday released a $160 million initiative to support bio-manufacturing initiatives (in addition to tissue regeneration).

Even with this new support, it may still be years before lab-grown organs become available, and we have a significant need that must be addressed today. Thus, we ought to focus on our current policy systems. Several European countries have an opt-out policy for organ donation called presumed consent. Under presumed consent a person is assumed to wish to donate their organs upon death if they (or their family) did not register indicating otherwise. Wales initiated the program in December 2015, and almost immediately saw an increase in organ donations. In Belgium, organ recovery more than doubled following implementation of the policy. With 95 percent of Americans supporting organ donation, but only half of the population registered, this program seems promising. It does have its critics, however, who propose an alternative: required response.

Required response is believed to create a centralized uniform system for collecting organ donation information, replacing the inconsistent state-centered approach. Required response can address the large number of individuals who indicate in surveys that they haven’t signed up to donate organs simply because they believe they were never given the opportunity to. Additionally, by declaring the decision through required response while we’re still alive eliminates the difficult decision for our family members and ensures that our after-death wishes are upheld.

Considering that, according to recent data, 2,596,993 people died in the United States in 2014, it’s difficult to imagine a waitlist of 120,000 for organ transplants if we focused our efforts on prevention, education, and advocacy. Reasons why people don’t donate come down to misunderstanding, mistrust of the medical profession, confusion over brain death, and discomfort in talking about death. Preventative medical factors are also involved: America’s obesity epidemic is actually reducing the number of organ donors. Despite being willing to donate their organs, a large number of potential donors are ineligible due to their weight. (According to the National Kidney Foundation, those with a Body Mass Index of over 35 are usually considered ineligible to donate a kidney.)

The Obama administration only recently recognized the importance of public education and advocacy in this area. The administration previously attempted to address a lack of donor registrations by prohibiting insurers from denying health coverage to someone with a preexisting condition, and by paving the way for transplants between HIV-positive donors and recipients, but that did little for donor registration. Just yesterday the White House hosted their first ever Organ Donation Summit. The summit acted as a call for education and advocacy to increase the amount of organ donation registrations. Social media was recognized as one of the most important modern instruments of advocacy. Organize, a nonprofit focusing on organ donation, released their plan to increase donations by mobilizing social media communities. Much like required response, the organization plans to create a database for donors through social declarations. Using the hashtags #organdonor or #organdonation, we can instantly register ourselves as organ donors on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. By the end of 2016, they hope to have registered one million people.

Did you know that a single donor can save the lives of eight people? According the the Department of Health and Human Services, after death, the heart, liver, kidneys, lungs, pancreas, and small intestines can be donated to eight people in need. Additionally, tissue donation from a single donor can make a significant impact in the lives of fifty people. As humanists who affirm the dignity and worth of each individual, we have a responsibility to focus our efforts on harm reduction, especially when immediate, viable, and inexpensive alternatives exist. Whether it be through a state-sponsored program or through social media, consider registering as a donor today.

Read Matthew Bulger’s rebuttal arguing in favor of using animals for human organ donation here.