Racism Past and Present Recognizing the Real Robert E. Lee

In the wake of the tragic events in Charlottesville, Virginia, this past weekend stemming from a white supremacist rally to protest the removal of a Robert E. Lee statue in the city, it’s worth taking a minute to remember the Confederate general. After all, the importance of commemorating history is the most commonly stated reason for preserving these monuments; so let’s remember.

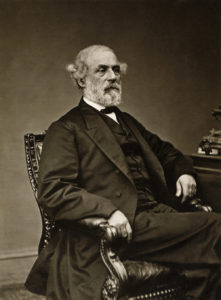

I’m not talking about remembering the lionized Bobby Lee, the sanitized version that has been imprinted into our national lore. I’m talking about the actual man behind the legend.

Every hero from our past has been washed clean of their less virtuous traits to some degree, but none more so than Lee. They refer to him as the “marble man,” because his legend has supplanted the historical man to a point where he is hard to find. Most know him as a noble, grandfatherly figure, fighting for the honor of his state and to protect his people from Northern aggression. To be sure, he was loved by his troops and by the South. He was a brilliant tactician, both on the offensive and defensive. He inflicted several defeats on a numerically and materially superior enemy against the longest odds. But he was also a failed strategist whose strategic endeavors failed on all levels.

Lee’s Maryland invasion in 1862, which he wagered would lead the state to a popular uprising in favor of the South, failed to gage popular sentiment in the region and ended at Antietam—a strategic disaster that gave Lincoln the leverage to issue the Emancipation Proclamation and keep Britain out of the war. His next invasion of the North ended in utter defeat at Gettysburg because of failed reconnaissance and an incredibly ill-advised charge. It cost the South resources and men they couldn’t spare. His defense of Richmond failed to anticipate Grant’s tenacity and the willingness of the North to endure casualties. He thought the North would never tolerate the loss of so many men to free the slaves; he was wrong. In fact, he committed a fatal error from the start, engaging his army in a conventional fight they could not hope to win rather than buying time to train and prepare them for their only real hope at victory, a protracted insurgency.

So there goes the myth of the infallible general. Now let’s look at the man himself. I’ve heard people say he was against slavery and treated his slaves with respect and kindness. In fact, he married into money and 200 slaves by betrothing George Washington’s great granddaughter. He promptly violated decades of tradition by breaking up slave families. Many of Lee’s slaves had expected to be freed upon their previous master’s death, but Lee had the will interpreted in a way that kept them enslaved until a Virginia court forced their emancipation. They hated the man. He was kind and affable to his troops but he had a horrible temper. He personally whipped his slaves and on at least one occasion not only lacerated his slave to the bone, he ordered his overseer to scrub the man’s back with brine.

When he invaded the North, he captured free blacks and sent them into slavery. When his men murdered surrendering black soldiers in the Battle of the Crater, he failed to stop it; he failed to investigate it; he failed to reprimand any of his subordinates; and he even failed to ever write or speak of having any regret that it occurred. When the survivors were paraded through the streets and humiliated, he stood by in silence when he could have stopped it. His silence spoke volumes.

When Ulysses S. Grant offered to exchange prisoners, as long as captured black soldiers were freed as well, Lee refused, despite his desperate need for men, despite the fact that his men were suffering in Union camps, and despite the hardship of caring for tens of thousands of federal troops. Lee’s response; “negroes belonging to our citizens are not considered subjects of exchange and were not included in my proposition.”

After the war, Lee argued in favor of “disposing of” blacks from the south. Here is a quote from his private correspondence: “that wherever you find the negro, everything is going down around him, and wherever you find a white man, you see everything around him improving.”

Here’s another; “You will never prosper with blacks, and it is abhorrent to a reflecting mind to be supporting and cherishing those who are plotting and working for your injury, and all of whose sympathies and associations are antagonistic to yours. I wish them no evil in the world—on the contrary, will do them every good in my power, and know that they are misled by those to whom they have given their confidence; but our material, social, and political interests are naturally with the whites.”

Publicly, in reference to black people voting and holding office Lee said: “the negroes have neither the intelligence nor the other qualifications which are necessary to make them safe depositories of political power.”

While president of Washington College after the war, Lee turned a blind eye to his students forming their own KKK chapter, to the attempted abduction and rape of black female students from a nearby school, and to several attempted lynchings by his students.

Lee was a failed general, a cruel owner and tormentor of fellow human beings, and, yes, he was unquestionably a white supremacist.

Clearly I remember my history without the need to ponder on it in the shadow of glorified figures on public grounds. In fact, I wager I’m more familiar with it than most. This isn’t about trying to forget our past—it’s about refusing to honor men who fought for an unjust cause. It’s about addressing injustice, then and now.