Reclaiming Black Queer Trancestors: Fighting K-12 Miseducation

Writer Abene Clayton and Liz Nsilu at LGBTQ+ Youth of Color Institute, Los Angeles, 2024 (photo by author)

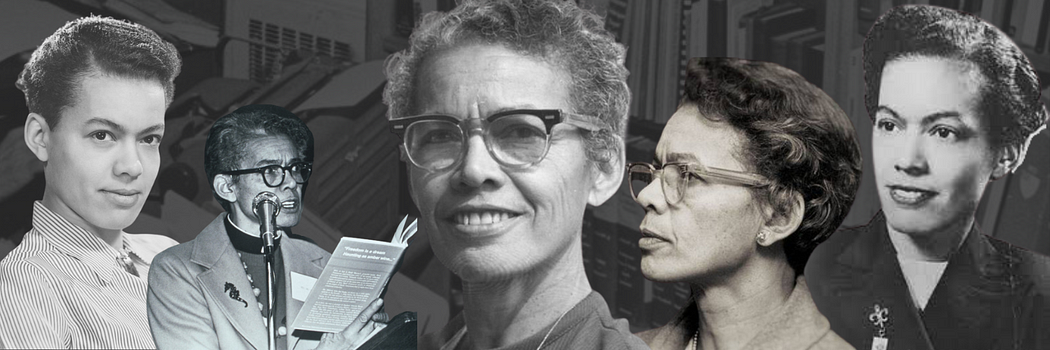

Writer Abene Clayton and Liz Nsilu at LGBTQ+ Youth of Color Institute, Los Angeles, 2024 (photo by author) Ask American adults across the political spectrum to name a U.S. Supreme Court case and the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision or the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision are the most likely examples they would cite. Ask them what trailblazing legal scholar and activist was central to both and they would most likely draw a blank. Tell them that a Black queer gender-expansive late-in-life Episcopal priest named Pauli Murray was one of the key intellectual architects of the legal theories that inform the democratic freedoms that many Americans have enjoyed, and it would be transformative for some and heretical for others.

The first Black person assigned-female-at-birth to be admitted to and graduate from Howard University Law School, Murray was a giant of twentieth-century civil rights law, as well as women’s and human rights activism. As a young Black girl attending L.A. public schools in the eighties, I was robbed of this education. Murray’s radical life and influence also remain largely unknown to Gen Z youth, who are more likely to identify as LGBTQ+ than any other generation in history. Bucking gender binaries, these youths are direct “descendants” and beneficiaries of the sea change Murray’s work had on our notions of race, gender, and sex in the U.S.

Murray’s writings and perspectives on Jim Crow laid the foundation for the legal argument that informed the Brown vs. Board decision. In a 1940s Howard Law seminar paper, Murray challenged the doctrine of “separate but equal” as a violation of the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. A decade later, Thurgood Marshall and the male legal team that argued Brown before the Supreme Court would draw on Murray’s arguments. In 1971, Murray’s ideas on gender inequity or “Jane Crow” (the term Murray coined to describe the intersectional disparities and legal restrictions women experienced) would be utilized by future Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg, lead attorney in the Reed vs. Reed case, the nation’s first successful sex discrimination case.

According to the Durham, North Carolina-based Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice, “Murray self-described as a ‘he/she personality’”. Scholars have also used the gender-neutral terms they/them to describe Murray. In their work and writings, Murray, who began identifying as male in their formative years and sought gender-affirming medical care in the 1930s, fought the rigid policing of gender. In my speculative fiction writer dreams, Murray and Stonewall trans hellraisers Marsha P. Johnson, Sylvia Rivera, and drag king Storme DeLaverie, meet and have a sit down about activism and the way future generations of queer youth will rise up to speak their truths against hate and erasure. Johnson, Rivera, and DeLaverie played key roles in the 1969 Stonewall New York City uprising against the normalized state violence, police brutality, and criminalization that trans communities of color were subjected to in bars, workplaces, and public streets.

As Black trans writer Dolores Chandler notes, “As queer and trans folks of color, our ancestors and our history are often hard to come by. We know that we have existed for forever but the world tries so hard to erase us or to explain our existence away as an anomaly or aberration. One of the ways in which society does this is by robbing us of our ancestors, and with them the knowledge that queer, trans, gender non-conforming folks of color have always been here.”

Given the toxic national backlash that Black LGBTQ+ communities are experiencing, education about the sociopolitical and historical influence of figures like Murray is potentially lifesaving for youth. Yet, even in the more “liberal” Los Angeles Unified School District (which has vehemently opposed parental notification and outing policies that put queer students at risk of being harmed and kicked out of their homes), consistent implementation of LGBT+ affirming material in English Language Arts and Social Studies classes is minimal. This is despite the existence of the California Fair Education Act, which mandates the inclusion of LGBT contributions in middle and high school history and social studies curricula. At Hamilton High School, my child’s current school, I have been frustrated by the glacial pace of “inclusion”. Outside of the one-semester ethnic studies course that ninth graders are required to take, utilization of queer authors, social histories, narratives, and other source material in the school curriculum is few and far between. And, even as district officials trumpet the availability of resources to bolster the mental health of queer students, the widespread use of homophobic and transphobic language among students, the marginalization of queer social history and literature, and fear among queer-identified faculty and administrators about coming out are insidious realities. I’ve expressed my views at faculty, parent, school site, and board meetings with sympathetic nods and chin-stroking platitudes.

Nationwide, incidences of anti-LGBT hate and mental health crises among Black queer youth have increased. According to the Trevor Project, “Twenty-one percent of Black trans, nonbinary, and questioning youth had attempted suicide and nearly half said they felt unsafe at school.” In addition, the Gay Lesbian Student Education Network’s (GLSEN) 2021 National School Climate Survey indicated that, “(While) less than 1 in 5 students said that they were taught an LGBTQ+ inclusive curriculum. LGBTQ+ youth of color are even less likely to see themselves represented in school books and lessons.”

WLP students presenting to King-Drew faculty, 2024 (photo by author)

For the past six years, I’ve trained youth from the Women’s Leadership Project (WLP) and GSA Network on how to administer the GLSEN climate survey at their schools. The survey measures campus inclusivity on such issues as the allyship of supportive adults, representation of LGBT figures and accomplishments in the curriculum, and whether school libraries have LGBT books. In addition to pushing back against anti-LGBT legislation and book bans, the survey can be an important tool for developing queer-affirming policies and practices that are driven by student perspectives. For example, during this past school year, eleventh and twelfth-grade peer educators Esther Abraham, Dafne Embarcadero, and MJ Leones were part of a team of students who conducted survey outreach and presented the results to faculty and staff at King-Drew Magnet Medical High School in South Los Angeles. The survey revealed that approximately sixty percent of students had heard homophobic comments (with over seventy percent saying they’d heard the term “gay” being used in a negative way). As a result of the data they collected, students recommended LGBTQIA+-focused assemblies and opening a campus clinic that would provide tailored sexual health resources for queer youth, who are often left out of reproductive and sexual health prevention education.

Supporting queer youth as they transform their campuses into safe spaces is the kind of advocacy that Murray—who was lovingly called a “boy-girl” by their favorite aunt—would have fiercely championed. As the 2024 presidential election looms, the prospect of a Project 2025 no holds-barred assault on LGBTQ+ rights poses an existential threat. With one eye to the future, our queer and trans ancestors dedicated their lives to holding space for descendant communities “yet to come”. It’s incumbent upon us to ensure that youth know about and can build on their visionary legacies.