Some Nice Talk but Where’s the Action? Pope Francis’s Address to Congress

The national media have been buzzing for weeks about Pope Francis’s visit to the United States. Perhaps what has most vividly captured the public’s attention about his sojourn, aside from the World Meeting of Families in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, is his speech to the US Congress. Joint sessions of Congress featuring a visiting dignitary are rare, and Francis is the first pope to address Congress.

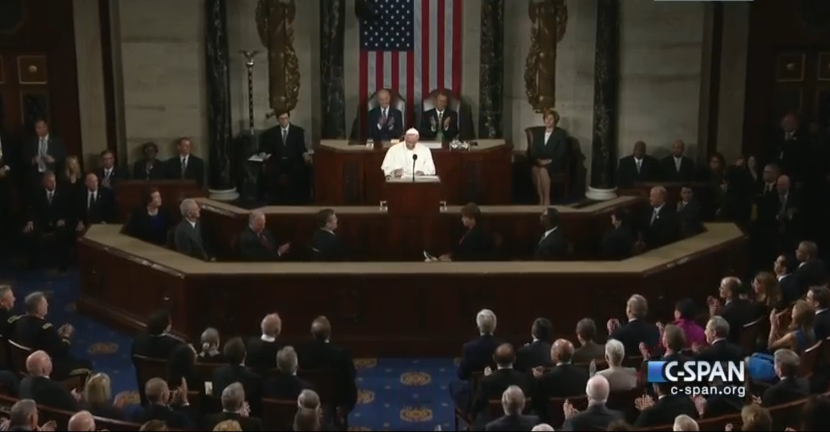

Screengrab via C-SPAN

But what businesses does the pope, a religious figure, have giving remarks at a joint session of what should be our secular Congress? The justification for this blurring of the line that should sharply divide church and state is that the pope is also the head of state of the Vatican, making him not only a religious leader but also a political one. Many humanists might still bristle at the notion that the head of the Catholic Church can assume to tell members of Congress and other government leaders what to do. Some conservative politicians, rejecting the popular pontiff’s emphasis on reducing economic inequality and combatting global warming, also expressed disapproval of Congress for inviting him to speak.

Having watched Pope Francis’s speech to Congress on a PBS NewsHour livestream, I found his words to be stylistically pleasant but politically bland. Francis made frequent mentions of “dialogue, solidarity, and fraternity,” all good things, and his address was full of the rhetorical flourishes that have inspired the media to dub him “the tweetable pope.” Yet I’m skeptical that his watered-down message will actually motivate members of Congress to enact these values in their dealings with each other in an increasingly polarized political climate. Making frequent mentions of shared values sounds nice, but it does little to inspire collaboration when each side of the political aisle seems bent on characterizing itself as in possession of these virtues while its opponents lack them. Humanists who are worried that the pope’s opinions on US politics may influence politicians are probably giving him too much credit. (Or perhaps I’m too cynical.)

That being said, the thrust of Francis’s message was positive with an almost humanistic tone. Though he asserted early on that humanity’s value comes from being created in the image of God and ended his speech by imploring young people to enter into traditional, heterosexual marriages and have lots of children, his other points focused on areas in which humanists and Catholics could find common ground. His populist emphasis placed working families at the center of political and economic life, and he called upon Congress to advocate for the vulnerable, not those already in power.

Specifically, Francis used four US historical figures—Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther KingJr., founder of the Catholic worker movement Dorothy Day, and social justice activist Thomas Merton—to illustrate the values that he deemed most necessary in American political life today: freedom, equality, compassion, and peace. He advocated for an end to economic inequality and insisted that business must exist to serve the common good. He encouraged empathy for immigrants and refugees by asking his audience to see others as fellow human beings. “We must not be taken aback by the numbers but see them as people, see their faces, and hear their stories…respond in a way that is only humane, just, and fraternal,” Francis urged. He then made a comment about everyone having “a responsibility to defend and protect human life at every stage of its development,” worrying me that he would begin speaking out against women’s right to reproductive freedom. However, instead of mentioning abortion, the pope called for an end to the death penalty, echoing decades of sentiments from the American Humanist Association and the humanist movement that rehabilitation, not retribution, upholds justice and human dignity. He also highlighted the urgent need for global action to combat climate change and encouraged the United States to employ diplomacy and dialogue over military and technological might in foreign policy.

None of these positive remarks negate the fact that Pope Francis has not changed Catholic doctrine regarding abortion and contraception, same-sex marriage, or women in leadership. The Catholic Church remains a patriarchal institution that allows men to tell women what decisions they should make about their own bodies and that denies legitimacy to same-sex couples. Humanists should continue to criticize the pope and the Catholic Church for its bigotry regarding these and other issues.

But humanists should not dismiss Catholicism in instances where we can work together for the greater good to better humanity as a whole. Unlike his predecessors, Pope Francis is emphasizing issues like economic inequality and global warming, in which there is overlap between humanist and Catholic values. Climate change is wiping out entire island nations, aggravating existing diseases, and contributing to food scarcity, and the dire problems that it is causing will only worsen unless all of humanity comes together in global cooperation to alter our social and economic systems so that they are more sustainable. With many US politicians still in denial that climate change is a reality and that it is caused by human activity, the pope’s call for environmental sustainability will likely go unheeded by Congress. It’s up to us, Congress’s constituents, to demand action on global warming, and in order to accomplish it, we just may need Catholic allies.

A transcript of Pope Francis’s speech is available here.