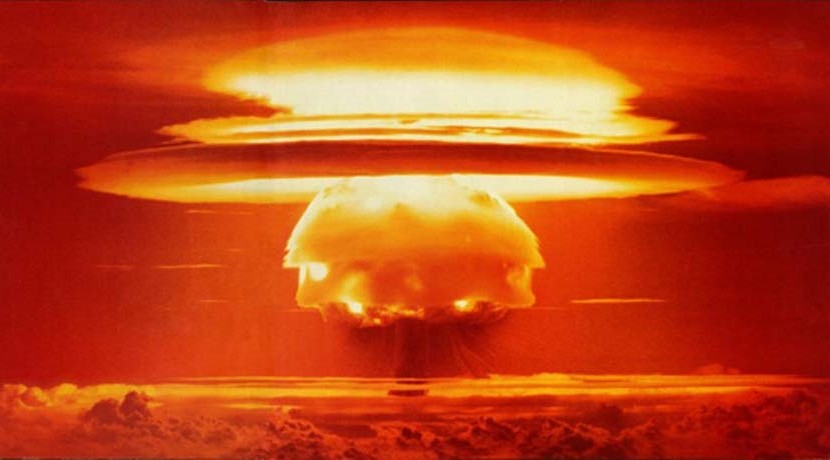

The Bomb: Reflections on the Anniversary of the Hiroshima Attack

On August 6, 1945, an atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, by the United States from a solitary aircraft; one of the members of the crew was someone I didn’t know at the time but later discovered was a very distant cousin of mine.

[A friend of mine, pretty and pushy] who was auditing the lecture went up after the 8 AM class and asked [the professor] about the atomic bomb. He took her outside and talked to her for twenty minutes! He said that they have bombs now that are 100 to 1,000 times as powerful as that dropped on Nagasaki, and they don’t really know what everybody’s got. Then she asked him, “Are you physicists afraid, and if not, why not?” He trembled and his face got white and he said they were terrified, that they used to be scornful of politicians and government but now they are afraid.

The amazing part of it all is that [another friend, equally intense] went up to the professor after the 12 o’clock class and asked him whether he was worried about the atomic bomb and if he’d heard about a new gas a cubic inch of which will kill all life—a rumor, she said. His face twitched and then he controlled himself and laughed, and the people standing around laughed. He said, “Have you got any gas that will destroy atomic bombs?” And that was that. She left, and we agreed that he was inhibiting himself because people were around, but why? The teachers at Wellesley were always letting themselves get carried away by ideas, but not here.

[In 1946, I think, I heard Lise Meitner give a special talk at Wellesley about her work in nuclear fission, which ultimately led to the bomb. I understood not a word of what she said, but I did understand the intensity of how she was saying it, and that fission could change the world.]

[In 1947] We were talking, and she said that some scientists she’d read give our civilization ten more years.

“Just think,” she said, “we’re at the height of our civilization. Mighty low, isn’t it?”

And you can’t get the ‘masses’ worked up enough to do something cause a) they can’t conceive of it, b) they wouldn’t believe it, and c) if they could, they’d probably say might as well have a damn good time while we’re still alive.

I apologize for my twenty-year-old self—for my fears and my snottier opinions—but in a way, I was right. There’s a lot that is not taken seriously today. I won’t sully your vision by repeating what the far-right politicians are saying about the likes of global warming, equal rights, and other issues. The frightening thing is that some of these politicians talk as if strength in war is what counts, no matter what happens to the planet. Are these people ready and willing to use any weapon that would give them control over the world? To return to my journal of 1947:According to 19th century science, on the basis of causality we are only mechanisms, along with everything else, and we cannot be free. But on the basis of uncertainty, our mental processes aren’t conditioned any better than [sorry, but I can’t read the equation I’ve written in smudged ink].

This seems like a small amount but as [the physics professor] said, extremely small events sometimes control large ones. An electron, “making up its mind” what it’s going to do, could set off an atomic bomb or not. Our individual freedom resides in some such uncertainty as this.

It is now 2015. We live in a very uncertain and dangerous world, of our own making, yet we should stop being so scared that it prevents us from thinking about what must be done to save ourselves and the planet. In the musical 1776 John Adams sings, “Does anybody care? Does anybody see what I see?” I hope I still see the consequences of the seventieth anniversary of Hiroshima. And since August 6, 2015, also means I am now eighty-nine, how much can I care? A lot. I hope you do, too.Tags: Hiroshima, World War Two