The Ought in Autism

Photo by Stephen Andrews on Unsplash

Photo by Stephen Andrews on Unsplash This essay was previously published in Etymology Press and is reprinted here with the author’s permission.

Ought connotes a moral obligation.

In our society, if you have a child with a disability, you are obligated to do everything in your power to make sure he succeeds. These are the things that we were told that every parent of an autistic person ought to do:

Get a diagnosis, as early as possible. You ought to exhaust all avenues of obtaining this diagnosis. This will be crucial to getting him the services he ought to have.

Our son was just a late talker. That’s what we kept telling ourselves. My husband’s brother and my own were late to talk, so there was no real worry. Yes, it was a little odd that he only wanted to examine the wheels on his cars from different angles, instead of pushing them around saying, “Beep! Beep!” like other kids. But it was also cool that he could take almost any small object, balance it on its end and spin it like a top. Perhaps he was destined to be an engineer.

After two and a half years, words finally came, but they weren’t “hello” or “mama” or even “wuv you.” They were entire paragraphs of the books I’d been reading to him. He wasn’t generating organic language—he was scripting (using memorized text or songs to express himself). He was letting us know how he felt by quoting passages from Benjamin Bunny or the TV show, Yo Gabba Gabba. By this time, we’d grown concerned enough to research autism and I knew scripting (aka echolalia) was a strong indicator that he should be tested.

The California Regional Center is an institution in California which provided services for people with cognitive disabilities. Once a person qualified as disabled, services were free (they were actually billed to California’s version of Medicaid called, confusingly, MediCal). It required a pre-screening evaluation to determine eligibility. Of course there was a long line of people trying to qualify for services. I tried for months to schedule an evaluation, but my emails and phone calls went unanswered.

We looked for another pathway and were happy to discover our health care provider had an autism evaluation program called Kid Clinic. We needed an appointment with my son’s pediatrician, who would refer us to the speech and language pathologist, who would then recommend us to the clinic. The first step took a month to complete. It took three months more to land an appointment with the Kid Clinic, where a speech and language pathologist, a pediatrician, a child psychologist, a physical therapist, a social worker, and a neurologist tested my son for three hours. In the end, my son stumbled out of the room and passed out in our arms as the team declared him autistic.

That was the day we cried. It wasn’t that the diagnosis was a surprise, it was just that we’d read enough to expect that his life and ours would not be easy, and we had no roadmap for what was to come.

When I contacted the Regional center again with our son’s clinical diagnosis of autism, they responded right away. They swore that ignoring my calls for months was a terrible mistake, that it was completely against their policies and they would look into the problem immediately. They also informed me that, despite this diagnosis, he would have to undergo another round of evaluations through the Regional Center itself to qualify for therapy and services. The earliest available appointment was four months away.

After nine months of testing and applying for MediCal twice (we were rejected the first time because we’d been sent to the wrong office), my son finally qualified for services.

I felt like we were at the beginning of a long journey. Our train hadn’t even left the station and I was already exhausted.

Once you have a diagnosis, you ought to obtain ongoing speech and behavioral therapies (Applied Behavioral Analysis – ABA), which will make him indistinguishable from other children (you ought to want that).

Now that we were solidly aboard the disability services train, the sales pitches began. We attended a mandatory orientation session at the Regional Center, after which we were hastily shepherded towards the state-approved providers of Applied Behavioral Analysis (seriously, the vendors were waiting in the room right outside the orientation, like vultures on a fresh kill).

If you are unfamiliar with ABA, look up dog training. It’s the same process, but with more note-taking. If you’re thinking that dog training sometimes uses aversive therapy like shock collars, look up the history of ABA and see that shocks were administered to autistic people too (in at least one large institution, they still are). But home providers of ABA extol the merits of errorless learning: the kid isn’t punished for doing anything wrong, but the desired behavior is demonstrated over and over until the child repeats it.

Our child learned early on to do what the therapists wanted just to shut them up. The only people who were successful in teaching him anything at all were people he liked, but ABA required demonstrating competence in a task across at least three different therapists. So if my son actually formed a connection with a therapist, they were quickly whisked out of his life to avoid contaminating the data.

My son was three-and-a-half and received two to three hours of therapy a day. At times we would hear him screaming and crying in frustration. We were told that this was a normal part of the process and were supposed to wait it out. We did not wait it out. We often stopped sessions and sent the therapist away to ease his pain.

ABA is grounded in scientific methodology, but we started to question its stated goals. What did it mean to be indistinguishable from other children, and why was that such a good thing? Who was that for? Was it supposed to make us feel better to see our child following a path that we recognized? Was it worth sacrificing his emotional well-being and agency to achieve that?

We often wish we had followed our instincts sooner. To this day, the biggest insult my son can hurl at someone in frustration is, “YOU’RE A THERAPIST!”

You ought to be a warrior mom (or dad), fighting to make sure that your child’s needs are met in a school setting through an Individualized Education Plan. He ought to be able to function alongside other students. The school ought to provide these accommodations.

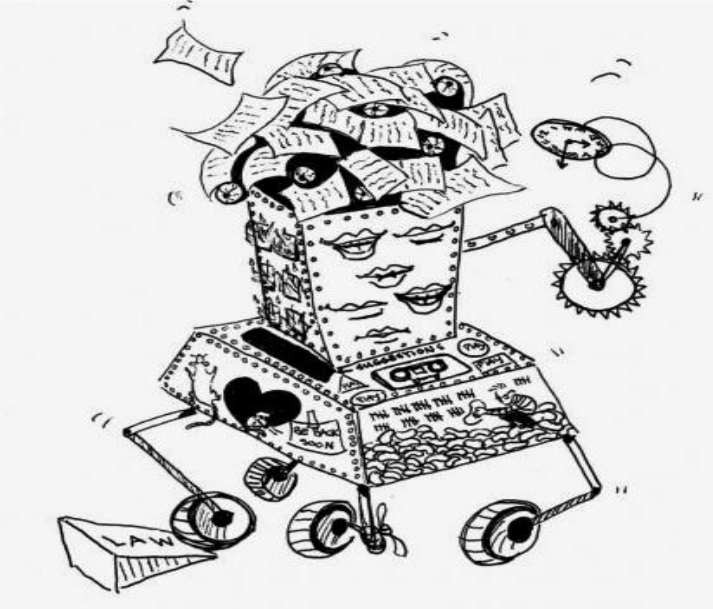

To give you an idea of what it was like to deal with the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), I’d like to share a little cartoon I drew on February 24th, 2010. I called it, How to Stop a Bureaucratic Machine.

At the age of three, a child was classified as “school aged” and would receive speech services (or funding for them) from the school district instead of the Regional Center. But of course, a new institution would require another round of tests.

All of this was happening at the same time as qualifying for Regional Center Services. Think of it this way: two trains were running on parallel tracks, bound for a town called Reasonably Successful Future.

The tracks for the Regional Center train ran on an Individualized Personal Plan (IPP)—a plan to help a person reach life goals with as much independence as possible, conducted by state and federal law.

The tracks for the LAUSD train ran on an Individualized Education Plan (IEP)—a plan to meet educational goals, conducted by FAPE (Free and Accessible Public Education), a federal law.

LAUSD and the Regional Center both tested my son at about an eighteen-month-old level for pragmatic speech (the ability to make sentences and hold conversations), but neither of their trains seemed to be in much of a hurry to get him to that Reasonably Successful Future town.

We paid for four hours a week of private speech therapy ourselves, while we waited for help from LAUSD to arrive. He was starting to make progress with the play-based therapy and we wanted to be sure he could continue, because our ability to pay for it ourselves was running low.

Our first IEP meeting with LAUSD was scheduled for January 28, 2010. We sat at a fake wood grain-topped conference table in Hamlin Elementary school with a special education teacher who was designated as the Meeting Leader.

At the start of the meeting she slid a brochure across the table: The IEP and You: A Guide for Parents, With Information About the Individualized Education Program (IEP) Meeting. She admitted that we were supposed to get a copy of it before the meeting, but the guides had been “delayed from the printer.” So, with no preparation, we listened to her discuss possible preschool placements and supports for our son.

We just wanted the district to cover his speech therapy. We asked about continuing the four-hour-a-week private therapy schedule, so that he could function in a classroom at the appropriate grade level. The Meeting Leader rejected our request and offered a half-an-hour a week of group speech therapy in a classroom setting. She noted that, if we were unhappy with the offer, we had the right to contest it through Independent Dispute Resolution, (IDR) or through Due Process.

It was as if she’d just said, “The train you were expecting to go to Manhattan is going to Weehawken instead (hey, it’s close, right?). You can take it, or get off at the next station and try to book another ticket.”

We chose to sign forms to initiate an IDR. Close wasn’t good enough.

We waited nine days for the call to schedule our IDR meeting, then contacted the program specialist whose number we were given to check our status. She referred us to the Due Process department, which referred us to a Speech and Language Pathologist Program Specialist (SLPPS), who finally returned our call.

The SLPPS asked why we were fighting for more speech therapy than the district had offered insisting, “studies show that language is best acquired in the classroom.” Unfortunately for her, we’d had time to read the study she was using to support her claim: LAUSD Position Paper #7. It said on page one that no autistic children were included in the study. When we asked how she could use Paper #7 to suggest that a classroom was the best place for an autistic child to acquire language skills when the study didn’t show that at all, the SLPPS abruptly ended the conversation, saying she’d “have to get back to us on that.”

On Feb 19th, 2010, the SLPPS finally called to address our concerns. She appeared to be following a tightly worded script, assuring us, in palliative tones, that LAUSD’s last offer was in fact the most appropriate placement for our son.

The rest of the call had the surreal quality of having a conversation with a telephone voice prompt system. No matter what argument we made, we were met with the equivalent of “We’re sorry, that is not a valid option. Please press star to return to the main menu to hear your options again.”

We decided that nothing useful would come of the call, so we asked if the district was ready to schedule the IDR meeting and make a final offer of FAPE. To our horror, we were told that this phone call was the IDR meeting and final offer of FAPE.

In effect she was saying, “This is a big train. It’s going to Weehawken. Good luck turning this thing around.” The SLPPS did say we had one last option. “Feel free to exercise your right to Due Process.”

In layman’s terms: “So, sue us.”

So, we did.

Our disability rights lawyer, Valerie Vanaman, was part of a legal team that had placed LAUSD under court supervision for failure to comply with the federal laws regarding accessibility in 2003. We were assured her name still inspired fear in due process hearings. After hearing our story, she pulled up a similar case out of hundreds of previous files, made a few changes and had a full game plan in under twenty minutes.

She explained that LAUSD used the Ford Pinto strategy in dealing with parents seeking services:

For those unfamiliar: from 1971 until 1980, Ford made the first subcompact car, the Pinto. It was a nifty little car, but its gas tank had a nasty habit of exploding and bursting into flames if the car was rear-ended, creating twenty-seven crispy corpses and a slew of badly-burned survivors. The company was well aware of the problem, but it did the math and concluded it was cheaper to pay off victims than to fix the problem.

Valerie explained that the lost brochures, kick-the-can phone calls, and nonsensical conversations weren’t a bug in the LAUSD system—they were a feature.

Fortunately, Valerie fully lived up to her reputation and got us everything my son needed. She also pointed us to the best behavioral agency in town, the Center for Autism and Related Disorders (CARD).

In case you’re lost in the timeline, the LAUSD train and the Regional Center train pulled into the station at Reasonably Successful Future town at the same time.

The Regional Center paid for CARD. LAUSD provided speech therapy, and my son was allowed to have an aide from CARD to assist him in the classroom instead of one assigned by the district. We felt like we had won.

From preschool through third grade, my son had every support he needed at home and in school. It all seemed to be going great, until it wasn’t.

Spelling was one of my son’s best subjects. One day, his teacher showed me a test he had failed. She explained, “It’s not that he didn’t know the words— he just quit half-way through the test.”

Part of the deal for him to stay in a regular classroom with an aide, instead of a special education classroom, was that he had to keep up during class and finish all of his homework.

One day, after six hours of school and two hours of therapy, the kid just wanted to play Minecraft. I suggested, “What if I ask you the questions, then you tell me the answers and I’ll write them down?” I called out the multiplication problems on the page, and he answered each one correctly, without hesitation, never looking up from his game. I remembered his failed, unfinished test and it all clicked. Oh my god, it’s too easy for him.

But that wasn’t the whole picture. In third grade, the emphasis of traditional learning switches from memorizing facts to analysis. Instead of being asked what is this? They would be asked why did this happen? and how do you know? My son’s brain was not wired for why and how.

One afternoon, I quizzed him for an upcoming test: “What is a prairie?”

He answered correctly, “a grassland.”

The response was so automatic, I pushed for more: “And what is a grassland?”

He looked at me blankly. “What?” We had reached the end of his memorized knowledge. He did not have the ability to contextualize information. I realized, from here on out, he would be screwed.

With every support in place, traditional school was suddenly both too easy and too hard. What do you do when something just doesn’t fit anymore? You take it off and find something that does.

Dig a little deeper into the history of the word ought, and you’ll find the word owe. We owed it to our son to promote his skills and help him build a life that was meaningful to him.

My son has a photographic memory and perfect pitch. He taught himself advanced font design, animation, graphics, and composing software. He could play anything by ear on the piano. He learned entire language systems and could demonstrate minor differences between similar language groups. In short, he was autodidactic. We did some research and learned that self-directed, home-based education was a legal possibility for him. We decided to make that possibility a reality.

To buck an ought, with all of its moral shadows, makes people uncomfortable. We truly cared for everyone who was dedicated to what they thought my son ought to do. A few were hurt that we walked away from their services. But those who knew my son best, understood that we owed him a chance to be who he could be rather than what others thought he ought to be.

Leaving school and quitting ABA happened at the same time. I called it an ice bucket challenge for the soul. It was an exhilarating and terrifying rush of emotions. I was sure we were doing the right thing, but cutting loose all of the people and things we had fought so hard for was disorienting.

The experts on both the LAUSD and Regional Center trains wished us well, while reminding us we could always come back if it didn’t work out. We waved goodbye, stepped off the platform, and never looked back.

How did it work out? My son graduated from high school in 2024. He is an award-winning animator whose films have been screened in nineteen festivals around the world. He’s performed with School of Rock and two independent bands in some of the coolest venues in Los Angeles, and his font designs on Fontspace have been downloaded over 30,000 times. He makes short YouTube videos for fun and his two main channels have gained over 17,000 subscribers.

I ought to take a moment to say that homeschooling an autistic child isn’t for everyone. Each parent ought to do what is best for their individual child. We owe it to them to find out what that is.