The Right Thing To Do A Humanist Argument For Syrian Intervention

It’s a rare confluence of circumstances that sees the likes of Rand Paul and Elizabeth Warren together on one side of an issue and President Obama and the Arab League on another side.

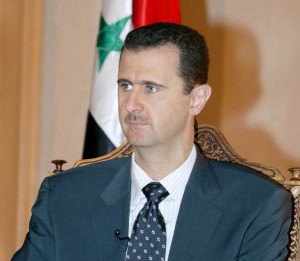

Yet that is exactly where we are with the current crisis in Syria. The global stage is calling for intervention following Syrian President Bashar al Assad’s sarin gas attack on rebel forces in August, with leaders from the Middle East, France, and the UK all calling on the United States to lead a strike.

But domestically in the U.S., as happened in the UK last week, politicians are divided, sometimes starkly so, on the issue of whether we should get involved in the Syrian conflict.

The problem comes down to the ever-present pull of isolationism against intervention. Should we, as American citizens, allow our country to become entangled in a conflict which has no direct effect on our lives?

But such a question ignores the basic beliefs we claim to hold about our nation, that we stand for justice, that our laws are dictated by a morality of human empathy, and that we do not just lead but are citizens of the free world.

Taking action in Syria is not a decision that should be taken lightly, which is exactly why it hasn’t been taken lightly. In the months since fighting began between Assad’s regime and rebel forces, there have been calls again and again for America to choose a side. The president chose to act diplomatically, joining a chorus of international voices in denouncing Assad and calling for him to step down.

Even now, when all the evidence from every major international intelligence agency points to Assad committing a heinous war crime, and with cover from the Arab League, who passed a resolution urging the United Nations to take action against Syria, and with support from French and British leaders, President Obama still took the bold step of requesting congressional approval before ordering a response.

Consider that for a moment. These are not the actions of a president who is out for blood. It’s easy to forget that Obama was elected in 2008 at least partially because of his prescient senatorial vote against the war in Iraq, but clearly he’s learned lessons from his predecessor’s mistakes, and will not seek unilateral action. He’s making his case to the elected representatives of the American people.

It’s a compelling case: America has agreed with the international community that chemical weapons must be banned and that their use constitutes a crime against humanity. All evidence available points to the fact that Assad has committed such a crime, and that makes an already globally-condemned dictator a verified war criminal as well.

Thousands of people have died at the hands of one villain, who has now crossed the boundaries of what we, as citizens of the world, should be willing to forgive. This has escalated beyond a civil war or a domestic conflict. To do nothing would undermine America’s claim to moral sanctity on the world stage, a position that has been undermined time and time again by either mistaken action, like the Iraq War, or inaction, like our ambivalence over the genocide in Rwanda.

There are purely political arguments to be made as well. Many Syrian rebels are backed by al-Qaeda, which has made supporting them with military force up to this point practically impossible. But by sticking by our stated position decrying the use of chemical weapons and taking a stand against a ruthless killer, America does not have to throw its support behind rebel forces, but can still do some diplomatic good by demonstrating that Western intervention in the Middle East is not universally unsound. Without having to take a side in a bloody war, we can still create new allies in the region.

There is no easy or truly good answer to the question of how to handle Syria. But America is, and has been, a nation that should stand for certain universal ideals, rules that we should all live by regardless of religion or background. The consequence of being an idealistic nation is that, from time to time, we have to be firm and rise to defend those beliefs. This is one of those times. We must punish and seek justice against a war criminal who has viciously slaughtered his own people. It is morally, militarily, and politically the right thing to do.

When your neighbor’s house is on fire, you lend them a hose. The Syrian people are burning. What will we do?