Using History to Find Hope in Our Political Future

The Republican Party is in the middle of a nasty, public divorce. The common affections holding it together, those being anti-abortion, anti-tax, and pro-gun, are being overpowered by the irreconcilable differences of pro-immigration versus nativism, free trade versus protectionism, and isolationism versus interventionalism. These tensions give everyone, liberal and conservative alike, an uneasy feeling. Previously, each had their enemies and the balance of power would shift regularly, but these changes seemed predictable and rational. Our political world had a constant to balance out the variables. The party platforms had changed over time, but that metamorphosis had been so slow as to be all but imperceptible. Few if any of us remember the Goldwater tide or noted the Karl Rove hijacking that brought evangelical moralism into the GOP base.

Fortunately, history can serve as our constant in a time of uncertainty. It can give us clues as to what is approaching over the horizon.

Since our inception, America’s politics have evolved through what political scientists refer to as party systems. Arguably we’ve experienced six such systems. For the sake of brevity I’m not going to delve into each one, however the same issues have always been on the table—they’ve just been espoused by different parties and even different factions of the same party over time. These issues are: popularism versus protection of minority interests; trade; the balance of power between state and federal government; the influence of the church on the state; the question of who is a human; our role in the world; and others. For an in-depth look at these issues, I’d highly recommend Howard Fineman’s book, The Thirteen American Arguments.

Some of these shifts in our politics from one party to another have been gradual, almost imperceptible, caused by shifting demographics over time, changing social norms, or economic hardship. Some have been cataclysmic, taking the form of the sudden snapping of a rope after years of building tension and rot.

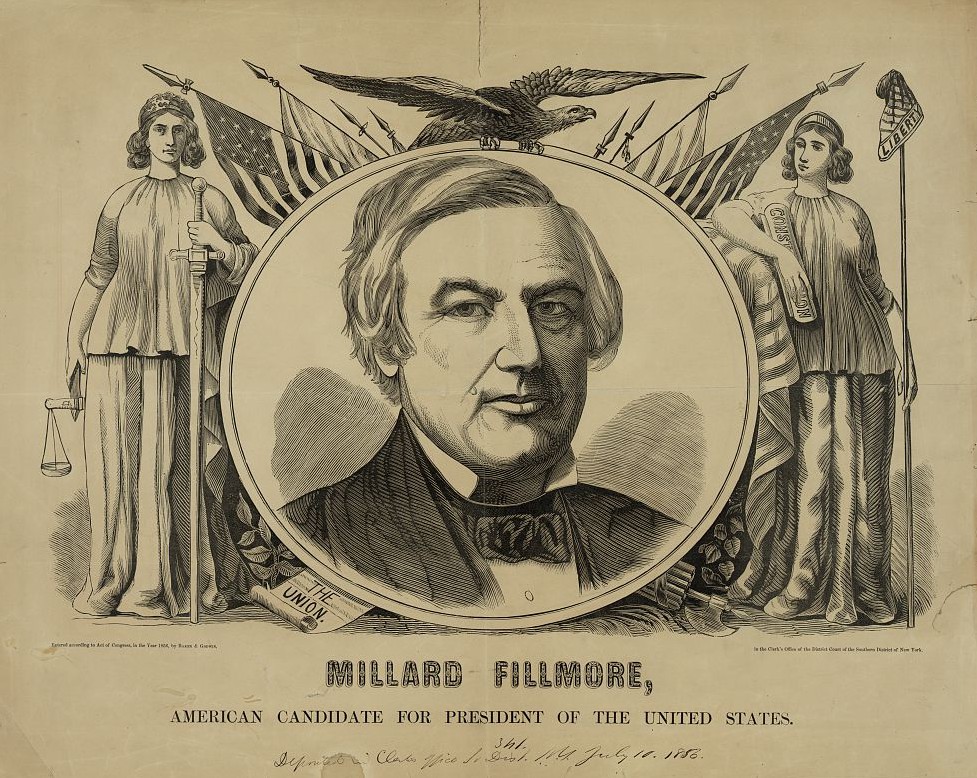

Millard Fillmore was the Know Nothing Party’s nominee for president in 1856 (campaign poster via Library of Congress)

We’re at the precipice of a jolting change in party systems, which is far from unprecedented. To grasp the familiarity of our current situation, you must first recall a lackluster and forgotten president, Millard Fillmore, the last of the Whigs. He took over as president after Zachary Taylor died in office, but Fillmore failed to win his own party’s nomination, not because he was ineffectual, which he was, but because a movement had ripped the party apart.

In 1853 the Whig Party imploded after having been the chief rival of the Democratic Party for decades. It stood for a strong federal government, protections for minority interests over populist tyranny, modernization, central banking, and public education. But the tension caused by divisions over slavery and protestant nativism had been slowly straining the affinity of its constituency for one another. These tensions all came to a head in 1853 and resulted in the rise of the closest thing we have ever seen to the Trump movement, the Know Nothing Party.

It was a national movement based on a fear of immigrants, especially Catholics and Chinese, and fueled by conspiracy theories and the fearmongering spread of disinformation. A main part of the Know Nothing platform was the insistence that the pope was attempting to take over America. Violent clashes erupted all over the country between Protestants and Catholics, like in Louisville, where a riot on Election Day, known as Bloody Monday, killed twenty-two people. Also, much like today, the Know Nothing Party was a truly anti-intellectual movement. It alienated and ridiculed those seen as the elites and the educated.

The Know Nothing Party completely took over the Massachusetts state government. While it did some positive things, such as expanding public education and advancing women’s rights, it is mostly remembered for its suppression of immigrants and individual liberties. It made daily reading from the Protestant Bible mandatory in public schools, it evicted Irish Catholics from state jobs, and it made it illegal for anyone to hold office in government who hadn’t lived in the state for at least twenty-one years.

The Massachusetts Know Nothing government instigated an investigation into sexual immorality in Catholic convents. Ironically, it was discovered that a leader of the investigation was using committee funds to pay for a prostitute.

Abraham Lincoln was a Whig but refused to become a member of the Know Nothings, saying,

“Our progress in degeneracy appears to me to be pretty rapid. As a nation, we began by declaring that ‘all men are created equal.’ We now practically read it ‘all men are created equal, except negroes.’ When the Know-Nothings get control, it will read ‘all men are created equals, except negroes and foreigners and Catholics.’ When it comes to that I should prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretense of loving liberty—to Russia, for instance, where despotism can be taken pure, and without the base alloy of hypocrisy.”

The destruction of the Whigs led to the dominance of the Democratic Party for the next eight years. The Northern vote was more split over the ordeal than the Southern vote, and this split resulted in successive and weak Northern Democrats being elected. Their enactment of the Kansas-Nebraska Act and tacit support for the expansion of slavery directly led to the Civil War. But out of the ashes of the Whigs rose a unified, progressive Republican Party, which for decades made great strides in the enfranchisement of freedmen, social spending, and establishing land grant colleges for higher education.

It’s a troubling and bewildering time in politics to be sure, but US politics have been through much worse. With a keen eye toward history, maybe this uneasy time can be seen as necessary and perhaps overdue. Maybe it is the catalyst that will lead to the rebuilding of a conservative party along more progressive lines and away from a party led by the nose by religious extremists, science deniers, and nativist bigots. Maybe this will give progressives the breathing room necessary to address climate change, for example.

If we look to history I believe we can take heart, because, much like in our past, this election has not created a divide or condoned bigotry and xenophobia, it has merely exposed it.