What Martin Luther King Jr. Taught Me

As we get closer to Black History Month I often find myself looking for information beyond what I like to call “Commercial Black History.” What do I mean by this? Well, it’s the histories trotted out, year after year, of Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King Jr., and you know, the guy who invented things with peanuts (I joke, I know his name is George Washington Carver). This history is taught to us in a generalized and commercialized matter from elementary school to well off into adulthood. We take the time to celebrate this familiar form of black history without taking into account its origin.

Black History Month grew out of something called Negro History Week (NHW.) The week was created in 1926 by the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH) and by historian Carter G. Woodson, an outspoken individual who was well-versed in the power dynamics of privilege and oppression. The creation of the week, proclaimed for the second week in February, was a way to critically shed light on the way schools indoctrinated students with white-oriented, anti-black education (and, I would argue, still do today). Woodson published The Mis-Education of the Negro in 1933 as a constructive critique of this oppressive educational system.

With time, NHW was adopted by education departments nationwide, but with the success came shortcomings. The ASALH pushed for literature and themes that incorporated the African diaspora into the history curriculum in public schools to no avail. As history progressed, the US government turned the week of history into four, recognizing Black History Month in 1970. Fast-forward fifty years, and far too little progress has been made to implement African-based history in our education system.

I am a product of that system. As a young Afro-Indigenous and Latinx woman, I didn’t know of my own history until I went to college. It wasn’t until I selected an elective (which should be required) called “Afro-Caribbean and Latino Studies” that I learned that Black history across the globe seems to follow the same pattern: colonization, oppression, and erasure of history. I was angry, bewildered, and fueled with a need to not only find out about my own history but that of the country to which I claim citizenship. With this, I searched for all forms of concrete history of this nation, including the history of well-known historical figures like the Reverend Doctor Martin Luther King Jr.

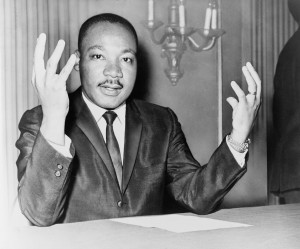

I shed light on Dr. King not because he’s the easiest name to remember when it comes to Black history but because of his humanism. King embodied the image of the non-violent, heavily religious, pro-church individual. But to me, he embodied the rational, non-violent humanist who railed against uncritical ways of thinking. So what especially did MLK teach me in my quest to find real, authentic history?

“Softmindedness often invades religion,” King said in a 1959 sermon delivered in Montgomery, Alabama, titled, “A Tough Mind and a Tender Heart.”

This is why religion has sometimes rejected new truth with a dogmatic passion. Through edits and bulls, inquisitions and excommunications, the church has attempted to prorogue truth and place an impenetrable stone wall in the path of the truth-seeker.

He also noted that “Softminded individuals are prone to embrace all kinds of superstitions…. The soft-minded man always fears change.”

We live in a world where things are often chaotic or confusing, which causes people to lean towards superstitions. A soft-minded individual is what I refuse to be. Again, in a world in which we are fed “truths” of our history, who we are as people, I want to make sure I live in a world of evidence, truth, and light. If change is necessary and logical, I embrace it. But I refuse to let my reasoning or stance on something be solely based on scripture or a preacher. I want critical thinking and thought-provoking knowledge. Truths that move me for good.

“The function of education is to teach one to think intensively and to think critically. Intelligence plus character—that is the goal of true education.” (“The Purpose of Education,” published in 1947 in the Morehouse College student paper, the Maroon Tiger.)

Very humanist from King, and he is right. Every motive, every decision, every word said or mentioned to another individual is to be thought of extensively and critically. Not only in the functions of education but, I would argue, to everyday life. Live with character. As part of the Humanist Manifesto III, to think critically and to have character is to live ethically. The goal is to live in a world in which we treat all persons as having inherent worth and dignity, and we learn this in part through educating ourselves in truth in its historical context. So that maybe in the future all marginalized people are treated with worth and dignity.

“Whatever your life’s work is, do it well. A man should do his job so well that the living, the dead, and the unborn could do it no better.” King said these words at the Holt Street Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1956.

Like King, humanists aim to live life to the fullest and with a deep sense of purpose. Whatever it is that brings such fulfillment, as he said, do it well. For me, it is creating a platform and a voice for Black, Latinx, and Indigenous people, reminding the world that we exist and we deserve to be recognized. Until I know that my siblings and fellow people of color are well, I will strive to do this work well.