The Houston Riot of 1917 A Century after 13 Black Soldiers Were Executed, Relatives Still Seeking Justice

The Historical Marker at the former location of Camp Logan in Houston. (Photo by James Jeffrey)

The Historical Marker at the former location of Camp Logan in Houston. (Photo by James Jeffrey) The streets of Houston down which rioting black soldiers marched 100 years ago are now inevitably gentrified with lovely looking houses, as residents—almost all white—walk their dogs and relax in the Texas sun.

Where the march began is now a tranquil park, with only a Texas Historic Commission sign marking the former location of Camp Logan. During its construction shortly after the United States entered World War I, it was guarded by the 3rd Battalion of the 24th United States Infantry, a predominantly black unit that on the rainy night of August 23, 1917, went on a rampage.

This summer just before Hurricane Harvey devastated Houston, the sign was rededicated to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Houston riot and those who lost their lives. The hurricane left the sign alone, but during the recovery and clean-up efforts, workers found vandals had smeared red paint over the segment of the inscription that read:

The Black Soldiers’ August 23, 1917, armed revolt in response to Houston’s Jim Crow Laws and police harassment resulted in the camps most publicized incident, the “Houston Mutiny and Riot of 1917.”

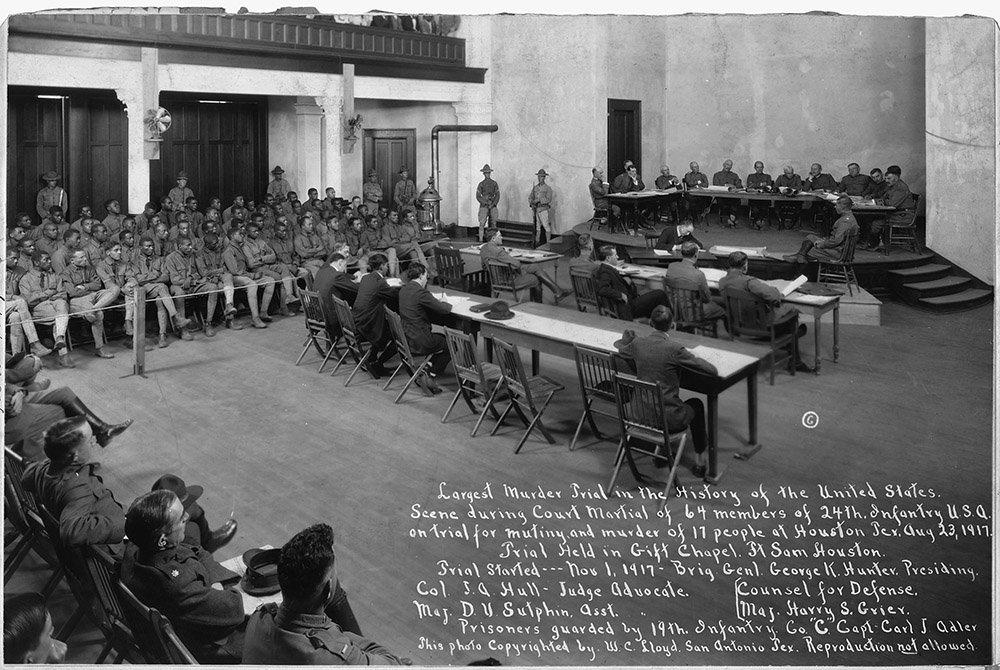

During the three courts martial that followed the riot—the first trial of sixty-four men proving the largest in US military history—a total of 118 enlisted black soldiers were indicted, with 110 found guilty, nineteen hung, and sixty-three receiving life sentences.

“They were denied due process guaranteed by the Constitution and died horrible deaths,” says Angela Holder, a history professor at Houston Community College and great niece of Corporal Jesse Moore, one of the hung soldiers. “They were represented by one lawyer and didn’t even have a chance to appeal.”

Court martial of 64 members of the 24th Infantry. Trial started 1 November 1917 at Fort Sam Houston. (Photo in public domain)

Although a majority of the soldiers were raised in the South and familiar with segregation, when they were dispatched in the spring of 1917 to Houston, as army servicemen they expected fair treatment during their service there. It proved wishful thinking.

“They sent these soldiers into the most hostile environment imaginable,” says Charles Anderson, a relative of Sergeant William Nesbit, another of the hung soldiers. “There was Jim Crow law, racist cops, racist civilians, laws against them being treated fairly in the street cars, while the workers building the camp hated [the soldiers’] presence.”

Ira Raney, one of the policemen killed during the riot, and the great grandfather of Sandra Hajtman. (Photo courtesy Sandra Hajtman)

Tensions continued to grow during the troops’ time guarding Camp Logan until the Houston police arrested a black soldier for interfering with the arrest of a black woman. When one of the battalion’s military police went to inquire about the arrested solider, an argument ensued resulting in the military policeman fleeing the police station amid shots, before being arrested too.

Though later released, a rumor reached Camp Logan that the soldier had been killed, coupled with talk of a white mob approaching the camp (there was none). After weeks of discrimination and tension, strained nerves snapped, resulting in more than 100 soldiers grabbing rifles and heading into downtown Houston. During a two-hour rampage, seventeen white people were killed, including five policemen. Four of the black soldiers were killed or died of wounds later.

The next day martial law was declared in Houston, and the following day the unit was dispatched back to its base in New Mexico. The court martial soon followed, held in the chapel at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio.

“It was dark and there was a big rain storm during the riot,” Anderson says. “At the trial not one civilian could identify a soldier firing shots that killed people.”

Seven mutineers agreed to testify against the others in exchange for clemency. The night before his execution, Private Thomas C. Hawkins wrote to his mother telling her not to be upset about him taking his “seat in heaven” and of his innocence. All the soldiers pleaded not guilty.

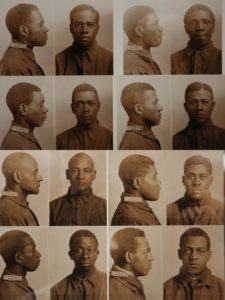

Soldiers who received life sentences. (Photo courtesy Angela Holder/ Buffalo Soldiers National Museum)

“The men did not have a fair trial,” says Sandra Hajtman, a great granddaughter of one of the policemen killed and whose career as a legal secretary also spurred her interest in the courts martial proceedings. “I have no doubt the men executed had nothing to do with the deaths.”

After the executions the US Army recognized that the lack of an appellate structure was unfair and changed their uniform code of military justice to prevent executions without a meaningful appeal.

“The soldiers were 100 percent wrong for rioting, but I don’t blame them,” says Jules James, the great nephew of Captain Bartlett James, one of the battalion’s white officers who managed to restrain a larger number of soldiers from leaving camp.” The unit had sixty years of excellent service, was full of experienced veterans but couldn’t endure seven weeks of Houston.”

Houston police and public officials viewed the presence of the black soldiers as a threat to racial harmony. The sight of black men wearing uniforms and carrying guns incensed white residents. Many Houstonians were concerned that if the black soldiers were shown the same respects as white soldiers, black residents might come to expect similar treatment. The soldiers themselves were angered by the “Whites Only” signs, being called the n-word by white Houstonians, and streetcar conductors demanding they sit in the rear.

“This was a problem created by community policing in a hostile environment,” says Paul Matthews, founder of Houston’s Buffalo Soldiers National Museum which examines African-American soldiers during US military history, including an exhibit on the courts martial. “It’s up to people now to decide whether there are lessons relevant to the present.”

In Houston knowledge about the riot varies—a rapidly growing city, most newcomers know nothing about an event that is rarely discussed.

“It’s not the sort of thing that builds tourism, after all,” says Mike Vance with the Heritage Society of Houston. “The city leaders might not trumpet it, but it remains part of the collective memory of the populace—I think that is true of things as recent as the race riots of the 1960s in places like Detroit and Philadelphia and even the Rodney King riots in LA.”

The centennial of the American entry into World War I has likely brought a heightened awareness of such events and emboldened people to address a sensitive subject, according to Lila Rakoczy, program coordinator of military sites and oral history programs at the Texas Historical Commission.

“What happened at Camp Logan is a complex narrative to navigate,” Rakoczy says. “There was no public acknowledgment of it for a long time, but now there is more willingness to talk about it.”

Jesse Moore (right), the great uncle of Angela Holder. (Photo courtesy Angela Holder)

Relatives of the executed soldiers have long known about the events, having grown up hearing them discussed by older family members, serving as an inspiration to some to look into the history more.

“I was six years old when my great aunt first told me about what had happened to Jesse Moore,” Holder recalls, “and how after his execution a package arrived at his mother’s house containing his coat, a dollar, and a letter that read: ‘By the time you get this letter, I will be in glory.’ Ever since I went to graduate school in 1987 I’ve been researching the history of the event and learning more.”

In addition to organizing the rededication of the Camp Logan historical marker, Holder helped lobby for gravestones from the Veterans Association for unmarked graves in a Houston cemetery of two soldiers killed during the riot. But the effort to obtain posthumous pardons for the hung soldiers has been unsuccessful thus far.

“We tried during the Obama presidency but missed out,” Holder says. “Perhaps we can approach a Texas politician or the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People [NAACP] to help.”

Earlier this year, the petitions for the pardons were sent to the Trump White House. The relatives are still awaiting a response on the 100th anniversary of the day of execution. Back in 1917 on a chilly December 11, the thirteen men condemned to death showed great bravery that moved all those watching, according to a written account by one of the soldiers overseeing the execution. None of the condemned men made any attempt to resist as they were taken from the trucks to the scaffold beside the Salado Creek of San Antonio.

“Not a word out of any of you men now!” proclaimed Sergeant Nesbit during the final moments.

Ceremony conducted this year at Houston’s College Memorial Park Cemetery to place two headstones at the graves of two soldiers killed during the riot. (Photo courtesy Angela Holder)

For decades no name appeared above the grave of Corporal Moore, only the number seven—corresponding to noose number seven, Holders says. Moore and those executed with him only received headstones in 1937 after authorities became concerned that flood waters from the creek might unearth the bodies, after which they were reinterred in San Antonio’s Fort Sam Houston cemetery.

“There are a plethora of events like this one throughout the history of our country,” Anderson says. “How do you stifle racism in America? I wish I could answer that question. What I do believe is that racism is a learned experience, it is taught; you don’t automatically grow up as a child hating people because of their color. If we could stop the teaching of racism in this country, and for that matter in the world, we could go a long way towards peaceful nations.”

While the relatives continue trying to made amends for the soldiers, some are also left wondering what might have been if the soldiers had been allowed to do their proper jobs in Europe with the other 350,000-plus African Americans who served in WW1.

“Instead of a noose around my ancestor’s neck they may have been hanging a medal,” Anderson says.