The Silent Polar Bear

Even now, I vividly remember my childhood visits to the zoo captivating me. Securely strapped in my stroller, I studied the animals firmly barred in their cages, so close I could almost reach out my hand and feel the hot breath. I had an overwhelming urge to rub the rough hide and pet the soft fur of the animals. Yet, I feared that if I touched one of the animals, it might fall to pieces in front of me.

Sometimes I would chortle at the colorful calls of the exotic Amazonian birds. Other times I would thrill at the belligerent bellowing coupled with the passionate chest-thumping of the apes from the African jungles. I would remain still at the snarl of the jaguar. Once, an elephant playfully doused my father in a red dust that covered the floor of its encampment. But I most vividly recall the silent polar bear who made watery slaps with its paws upon the hard, wet stone floor of its open air display, separated from me by a fence and a deep, wide pit.

Eventually I grew older and was able to see beyond the barriers of the animal cages. I then understood both the effect of captivity on these animals, and my own passive participation in looking at them through glass and iron.

Although San Francisco is foggy for a majority of the year, in my memory the sun always made a special appearance for our family day at the zoo. The gentle lulls of the Pacific Ocean mist made everything calm for the humans as well as for the animals. Zebras pranced in the artificial savannah while monkeys swung from branch to branch in a small cluster of trees. But it was the enclosure at the very back of the zoo, isolated from both visiting patrons and other caged animals that captured my attention.

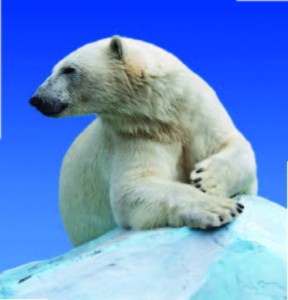

The polar bear, or ursus maritimus, is a mammal native to the Arctic ice sheets and the vast expanses of water that surround them. Their webbed paws make it so they are especially apt at swimming. Polar bears need to swim not only to satiate their carnivorous diet but to maintain a body mass necessary for survival in one of the coldest regions in the world. This silent polar bear’s accommodations are a swimming pond, a pile of rocks, and a coastal climate.

The silent polar bear is able recognize its substandard conditions. Polar bears, according to research scientist Alison Ames, are highly cognitive creatures that are just as smart as apes. They also have heightened senses of smell and sight, which are necessary for Arctic survival.

The silent polar bear reminds me of one of the homeless old men on the city streets outside the walls of the San Francisco Zoo. The bear’s matted fur droops, lacking the natural bristle to keep it up. The bear over-groomed its fur to a point where the twisted brown strands hanging from its abdomen are akin to a worn mop rather than a proud pelt. Head lowered, the beast appears distracted, as if it’s too dejected to see the pond, the rocks, or me again. With head bobbing side to side, the caged animal paces back and forth, a cynical representation of the plush memorabilia being sold at the gift shop out front. The homeless old man has the freedom to move about. The silent polar bear just paces on its slab of hard, wet rock.

Just as the sun, it takes the same path every day, back and forth, east to west. Like a metronome. I’ve always wondered what the silent polar bear wonders. Does it think…or does it wait?

On my last childhood outing, I left the zoo with a fuzzy white ghost haunting a fuzzy part of my memory. I saw the silent polar bear after I lost my first baby tooth. I saw the silent polar bear after I made my first friends. I saw the silent polar bear on a school field trip. I am growing up with the memory of a silent polar bear, a polar bear that with its silence, loudly projects the reality of animal captivity.

Many well-meaning zoo patrons believe that captivity is the solution to the polar bears’ endangered status. Polar bears need their space and should not be kept in a confined area. Captivity revokes its natural instincts. They will never be able to migrate, hunt at night, or claim territorial rights. Captivity can turn out quite badly for the estimated 1,000 of them pacing and slapping their paws on the hard, wet stone floor.

Polar bears are known to swim in excess of forty miles across the open sea. They are unable to do that in a small pool that spans forty yards. Polar bears are known as solitary creatures, and prefer to take long walks along ice sheets and snow drifts. They are unable to do that in captivity. They can only pace on the hard, wet stone floor.

I think what first made the silent polar bear distinctive to me at the San Francisco Zoo was his distinction from the other noisy animals. He lost his roar, that ear shattering territorial proclamation that justified what he had was his own. He no longer proclaimed what was given to him simply by birthright. Captivity effectively silenced my friend.

I have visited other zoos and other animals, but I am haunted by the silent polar bear. I still see the display at the very back of the San Francisco Zoo. I still smell the wet fur that clung to his ribs. I still feel the vibrations of his paws smacking the hard, wet stone floor.

Years have passed. The slap of the paws has grown louder inside of me. The slap of the paws has grown so strong inside of me that they became an entire roar of their own. The silent polar bear prompted a newfound passion inside of me, an advocacy for animals that have been robbed of their dignity.

In a quest of advocacy for the silent polar bear no longer silent in my mind, I emailed the head zookeeper at the San Francisco Zoo. I politely inquired why the silent polar bear behaved so strangely. Like the polar bear, the zookeeper is also silent. My email was forwarded to the public relations manager. In her response, she carefully explained how the silent polar bear’s behavior was perfectly normal. I didn’t reply. Like my friend, I can be silent, too.

After a quick Internet search, I read that the silent polar bear suffers from zoochosis. In 1992, Bill Travers, the well-known English animal rights activist, coined the term zoochosis to describe the obsessive, repetitive behavior exhibited by animals held captive in zoos.

Specifically, this animal-specific psychosis refers to a range of mental problems that are brought on by the stress of captivity and the inability to express natural behaviors. Symptoms of zoochosis include over grooming, neck arching, head swaying, and pacing.

I recently went back to the San Francisco Zoo. It was just as sunny as all my prior visits to see the animals. I saw the birds, the apes, and the jaguar. It was one bear that I wanted to see in particular.

The silent polar bear looked the same, was in its same place, and was making the same motions. A child with his family next to me asked aloud, “Why doesn’t he do anything?” I turned away from that, thinking, “Why aren’t I doing anything?”

Every day the silent polar bear casts its shadow upon the hard, wet stone floor. It also has cast a shadow on me. The treatment of this polar bear is not moral, not ethical, and does not benefit the commonwealth. I am heartbroken, enraged and ultimately deeply shamed that the employees of the zoo do not acknowledge the silent polar bear’s irregular behavior. And the worst thing of all is that I can do nothing to save my friend.

I refuse to be silent. We can help animals that are held in conditions that compromise their mental and physical integrity. In honor of the silent polar bear, I will be a lifelong champion of the rights of these animals.

There are many more animals that need to be saved. The panda bear. The dolphin. I am fully aware that not every animal can be saved. The silent polar bear’s paws slapping on the hard, wet stone floor will forever echo inside of me. It is my goal to give back animals their purpose. The purpose of the panda bear is to climb the foggy mountains of China, not a tree in a glass enclosure. The purpose of the dolphin is to swim in the vast expanses of the ocean, not in a small, enclosed tank with tourists in an amusement park. The purpose of the polar bear is to gallop along the frozen tundra, not to pace back and forth on the hard, wet stone floor while suffering in silence.

My purpose now is to be vocal, persistent, rousing. Anything but silent.