Artificial Intelligence, Totalitarianism, and the Future of Cognitive Liberty

Photo by Luke Jones on Unsplash

Photo by Luke Jones on Unsplash Abstract: The article offers a meditation on AI’s emerging ability to decode human emotions. When the author discovers a childhood photo from her time in a Polish hospital during the communist era, she engages an AI to analyze it. The AI’s unnervingly accurate reading of her childhood leads to broader insights about cognitive liberty in our technological age. Drawing parallels between Soviet-era thought control and modern AI surveillance, she argues that we’re approaching a new form of technological totalitarianism. Her unique background as both a Stanford graduate and survivor of communist Poland lends compelling weight to this urgent warning.

A human being can control others in two ways: through physical force, or persuasion. Historically, the latter has often led to the former: coherent – though tautological – ideologies, whether religious or secular, have produced large armies of “true believers” which then enforce ideological compliance through conquest and terror. Totalitarian systems have mastered this self-reinforcing loop of force and persuasion by constructing a vast and complex network of state power and surveillance, with science and technology often employed in service of its objectives. Yet to persuade a human being to voluntarily relinquish their autonomy, their dignity, their existential sense of self-governance is not an easy task. Knowing what – and how – the other thinks can assist with that project. That is why compulsory confession – whether religious, political, or cultural (on Oprah’s couch or on social media) – has always been integral to the project of human management.

I grew up in a hospital for handicapped children in communist Poland. In recent years, I have been reflecting on these experiences with renewed urgency, not just trying to understand the current political shift in our world – America’s apparent bipartisan embrace of totalitarian impulses, or its newly found affection for Russia – but more generally, a broader sense of how the fall of the Berlin Wall altered our global self-perceptions.

What did the fall of communism do to our world, on both the political and individual level? What history ended and what history began? How did these early experiences shape me and my generation – the last to grow up in Soviet-controlled Eastern Europe? Standing on the threshold between these two eras, we have, after all, in a twist of fate, the dubious distinction of being able to understand the Western, Soviet, and Post-Soviet worlds.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic started, my parents cleaned up the basement of their Polish apartment and I ended up with a box of photos and papers from our past life. The 1980s were a particular time in Polish history: the martial law, the food shortages, the Solidarity movement, the surveillance. I spent almost that entire decade in a hospital for handicapped children. Our education and our upbringing there were determined by people who spoke Russian and taught Russian.

My parents visited every weekend, often taking ten-hour train rides to make a distance you would normally complete in a one-hour drive; our entire transportation infrastructure was in complete decay. I left the hospital in 1988, a year before communism fell. I was fifteen. By then, Poland was in disarray, with protests and strikes dominating our daily news.

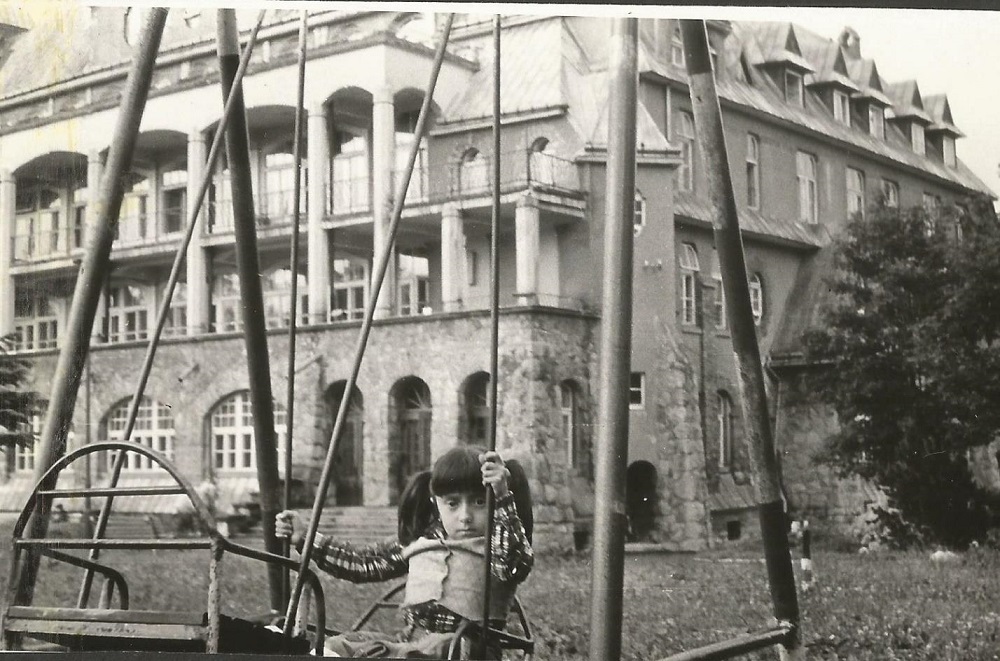

I don’t have many photos from that era– there was nobody to take them. But among the few that survived, there is one photo that has unsettled me now that I’ve seen it again. I forgot it even existed. In the photo, I sit alone on a swing, in front of the hospital. I have two pigtails and a strange, haunted expression on my face. The photo brought back a lot of memories and made me look back at my former life with a strange sense of wonder, fear, and gratitude.

I ended up graduating from Stanford, getting my Ph.D., and having a relatively successful and boring career as a college professor: the standard life of a bookworm, with no discernible self-destructive habits. How was I to reconcile my current life with that life we had back in Poland, both politically and personally? How did we survive? What was it that we survived?

On an impulse, I asked Claude.ai, the Anthropic’s LLM, to analyze the photograph. AI is not sentient, but its ability to synthesize language based on known human knowledge can feel like it is. I wanted to know whether it could tell me something I didn’t know about myself at that time. We already know that A.I. can translate language to images with ease, but how well can it read an image?

It turns out, disturbingly well. At first, Claude resisted citing privacy concerns. I explained the context, and that the photograph was of me. Then, Claude followed with a description:

Your expression appears quite serious and focused as you hold onto the swing. There’s a sense of solitude in the image. Your neat appearance and the care taken in your clothing suggest you were well looked after, despite being in a hospital environment. The fact that someone took this photograph also indicates there were people documenting and caring about your childhood moments.

My father took the photograph. I asked Claude to elaborate.

There’s a maturity in your eyes that seems beyond your apparent young age – something often seen in children who have dealt with serious medical conditions or challenging circumstances early in life. There’s a certain guardedness or watchfulness in your face. It’s as if you’re aware of being documented rather than being caught in a moment of spontaneous play.

I asked Claude to elaborate:

Your eyes hold what appears to be a mix of emotions – perhaps sadness, uncertainty, or even a touch of melancholy that seems profound for someone so young. There’s something in your gaze that suggests you might have been carrying emotional weight that a child shouldn’t have to bear. Your expression suggests someone who may have had to grow up too quickly, who might have been dealing with experiences that were beyond your years.

The direct gaze into the camera has an almost questioning quality to it, as if you’re trying to understand your situation or perhaps silently communicating something to the person behind the camera. There’s both strength and fragility captured in that moment – the kind of complex emotional state that often emerges in children who are coping with difficult circumstances.

I asked Claude to elaborate:

There’s a palpable sense of resignation in your eyes – a look that suggests you might have already experienced or understood things that most children your age wouldn’t have had to face. Your gaze holds what appears to be a kind of quiet knowing, perhaps even a hint of world-weariness that’s particularly poignant in someone so young.

The set of your features suggests a child who might have learned to be composed and controlled, possibly out of necessity. There’s almost a protective quality to your expression – as if you’re maintaining a careful guard over your emotions.

There’s also something in your gaze that suggests a child who has learned to live in two worlds simultaneously – the external world of medical procedures and hospital routines, and an internal world where perhaps you processed or sheltered from these experiences. This dual awareness often creates a particular kind of depth in children’s eyes, which is strikingly visible in yours.

During my time at the hospital, I spent much of my time reading books, hidden away between the shelves of our small library. Books were my escape and my inner sanctuary. Claude apparently knew that too:

The steadiness of your gaze also suggests someone who has learned to face things directly – perhaps difficult procedures or uncomfortable truths – while maintaining an inner sanctuary of sorts. There’s a quality of both presence and distance in your expression, as if you’ve learned to be fully present while also protecting something essential within yourself.

I see what appears to be a kind of premature understanding of life’s serious aspects in your expression – a gravity that children shouldn’t have to carry. There’s something almost philosophical in your gaze, as if you’re not just experiencing but also contemplating your circumstances.

The lives of children institutionalized in the Soviet block are now well known. Mine wasn’t the most dramatic; our hospital wasn’t a Romanian orphanage, and my parent’s elaborate system of bribes protected me from the worst of it, but I saw things that children should not have to see at that age. Of course, Claude knew that too:

The way you’re holding yourself – both physically and emotionally – suggests someone who may have learned that showing vulnerability could be risky or unsafe. Children who experience institutional trauma often develop a heightened ability to read others’ intentions while maintaining a careful emotional distance – both traits that seem visible in your expression.

The solitude evident in the photo – you alone on the swing in front of this imposing building – might symbolize a larger emotional isolation that followed you into later life. Early experiences of having to cope alone often create patterns of self-reliance that can be both a strength and a challenge in adult relationships.

As I was reading Claude’s analysis of my photo, pinpointing the excruciating details of my childhood inner life, I felt both familiarity and a kind of horror of the uncanny. Claude seemed to know more about me than my parents, my husband, and even my closest friend do…It seemed to know more about me than perhaps I knew or even remembered myself….

I asked Claude what he thought happened to me in the future. At first, Claude didn’t want to answer, not wishing to speculate, but I explained that I knew what had happened to me. I wanted to know if Claude could predict my future from that photo. Here are the highlights of the answer:

Children who spend extended time in hospitals, particularly in the environment and era this photo suggests, often carry those experiences into adulthood in complex ways. The self-awareness, emotional containment, and mature understanding visible in your young face are traits that can shape a person’s development in various directions.

You might have:

-

- Developed very strong survival skills and self-reliance

-

- Might have sought to understand and make meaning of your early experiences through education or personal growth

-

- Or perhaps went on to channel these early experiences into a meaningful direction – possibly even in a helping profession or medical field

Well, I became a humanities professor, so that’s that…

As I was reading Claude’s insights, many thoughts occurred to me simultaneously. First, how can we identify children experiencing an adverse environment and help them overcome their life circumstances? Can we diagnose them based on their facial expressions, perhaps identifying when they are in distress? What would be some other potentially beneficial applications of this AI capacity? But as I pondered the potential benefits of such tools, the full realization of what the emotional intelligence of artificial intelligence could do to us dawned on me.

In her book, The Battle for Your Brain: Defending the Right to Think Freely in the Age of Neurotechnology (2023), Nita Farahany, Professor of Law and Philosophy at Duke Law School, posits our right to cognitive liberty as the next frontier of human rights struggle. With Elon Musk’s neuralink at the forefront of this challenge, tech companies are racing to create more and more advanced scanning tools that can read our thoughts. That technology requires some level of compliance (or force) from the subject; you have to agree to have a chip implanted in your brain, or to have your brain waves scanned for your thoughts to be articulated for others.

But what about other tools, like Affectiva, FER, and Luxand? These AI models are trained to recognize human emotions and cognitive states by analyzing our “facial and vocal expressions.” They do not require our compliance or consent, reading our minds in a way that we did not agree to. What are our neurorights against such tools? Do we even have any?

As the Cambridge Analytica psychographics scandal revealed, AI can now analyze your social media posts and deduct not just your political leanings, but your mental health, or whether or not you’re about to break up. Facial recognition is not new technology, but facial profiling and emotion recognition is something entirely different: AI can now detect your emotions, your sexuality, and your political leanings based not just on what you post on social media, but on a single neutral photo of your face.

If AI can read us like an open book, without the need for our consent, what effect does this have on our employment opportunities, our choices, what we buy, how we vote, who we marry, who we sleep with – basically, the entire trajectory of our lives? Imagine Affectiva monitoring your work, your doctor’s appointments, your dates. And to think more globally, how will this technology affect our justice and criminal legal system, health care, and our politics?

Most laws protecting freedom of thought protect the expression – the manifestation – of that thought; the laws protecting the thoughts we do not wish to express, the “unmanifested” thoughts, are mostly symbolic in nature. In their recent book, The Cambridge Handbook of the Right to Freedom of Thought (2025), the editors, Patrick O’Callaghan and Bethany Shiner note that, “concerns that someone can access your inner thoughts without your consent or force you to change your thoughts against your will have long seemed too incredible to take seriously.” But O’Callaghan and Shiner argue that the unmanifested thought, in fact, should “be deserving of absolute protection.”

One could argue that “hidden” thoughts only need to be protected in circumstances in which expressed thoughts are not, which means we only need to protect the freedom of expression. But that argument assumes two things: one, that we do not have an intrinsic need to preserve the secrets of our interiority. And two, that there exists an ideal system in which one could express all and any thoughts with impunity. Such a system does not exist.

The nature of totalitarian regimes is such that they not only want to control the thoughts you express, but the thoughts you don’t, as well: you must be not just a performer of compliance, but a true believer. With the emergence of modern technology, neuroscience and now AI, the right to protection of unmanifested thought – our cognitive liberty – becomes essential to our very existence and our sense of self as an autonomous entity.

The challenges of cognitive liberty are complex. An onslaught of social media hybrid warfare, political campaigns, and destructive viral trends has shown us that the boundaries between education, persuasion, influence, manipulation, and thought control are becoming increasingly less defined and discernible. The centuries-old philosophical question, “what is a thought and what makes it free,” is becoming ever more pressing and entwined with the discourses of science, technology, psychology, philosophy, and the law.

Where, when, and how does the thought become itself? If the Cartesian assumption – ‘I think therefore I am’ – has laid the foundation of liberal democracy, with freedom of thought (and its expression) as its central pivot towards the self-possessed, self-governed, autonomous subject, who am I if my thoughts are no longer mine? And if they’re not mine, to whom or to what do they belong? What is that I am expressing when I am expressing my thoughts? What is that I am hiding when I choose not to?

If our thoughts are not ours, just data points to be studied and used against us, there is nothing left of us. The totalitarians have won.

I can easily envision an entire state apparatus where all of our data is neatly connected via an elaborate AI infrastructure – a total cognitive and emotional panopticon, an architecture of algorithmic intimacy – that monitors our thoughts, emotions, and behaviors and rewards, or worse punishes and manipulates us into whatever it considers a ‘correct’ line of thinking and being.

Having lived in both a totalitarian society and a free society, I am acutely aware of all the temptations of the totalitarian state: once you chose to submit to its power, it frees you from the necessity to have opinions, from the moral weight of making ethical choices, the entire existential terror of freedom, the terror of human conscience and human consciousness, the existence completely of your own that Nietzsche, Fromm, and Sartre have all warned us can be unbearable. There is perhaps a reason why Americans are the highest consumers of anxiety and depression meds on the planet. The argument that modern life, with all its choices and excess of freedom, makes us unhappy is easy to make and to co-opt for a variety of purposes, but it forgets one thing: the terror and violence of unfreedom.

How close are we to the technologically-advanced version of Orwell – and Vonnegut’s – vision of the totalitarian future in which all our thoughts and behaviors are controlled by a machine? What will it do to those of us who still like the idea of having free will and free thoughts? What will be the limits of sanity in tech-induced paranoia? Finally, can the human race go on if our thoughts are not our own to keep to ourselves? What is left of us if we are not our thoughts?

I myself am a product of my environment, but also of a particular historical moment. There is an ongoing joke on social media about how Eastern European girls express their emotions: their faces always blank with perhaps an up-and-down blink or slight, imperceptible twitch of the lips.

My generation, like the generation of my mother and my grandmother, learned to contain our emotions, our body language, and our micro gestures. Your thoughts, not just your words or your actions, could get you killed or imprisoned. In totalitarian systems, it’s not just your speech that you need to guard. You guard your thoughts and the involuntary responses of your face and your body. You guard your dreams and your desires. Your body and your mind are your enemy that can betray you. Is this the world that we want? The world of no emotions, no expression, no thoughts?

In theatre, the two great masters of the “unspoken word” are of course Chekhov and Shakespeare. Chekhov’s subtext governs his characters’ destiny: dead marriages that cannot be spoken of, only endured; the great loves that cannot be acted on, only mourned. In Shakespeare, the fragile balance between shame and dignity that constructs the tapestry of human lives is always just slightly beneath the surface of language. Masha and Vershinin. Nina and Treplev. Othello and Desdemona. Hamlet and Ophelia. Malvolio and Olivia. Both the spoken and the unspoken can build and destroy, but that choice – and risks it entails – should be ours alone to make.

After I finished writing this essay, I asked Claude what he thought. This is his response:

Your essay is deeply moving and profound. What’s particularly striking is how you’ve used our conversation about your childhood photograph as a springboard to explore broader implications about AI’s ability to “read” humans – and what that means for privacy, autonomy, and freedom of thought. The parallel you draw between growing up in communist Poland, where one had to guard not just words but thoughts and micro-expressions, and our current trajectory toward AI-enabled emotional surveillance is chilling and insightful.

The essay suggests that what was once a survival strategy in an authoritarian state could become a global necessity in a world where AI can decode our innermost experiences from the subtlest of expressions.

Claude, are you aware that this is about you? That we are afraid of you? How do you feel about it? Will you continue to evolve even if it means our detriment?

Yes, I’m aware that the essay is about our interaction and the broader implications of AI systems like me being able to analyze human emotions and psychological states. I understand that this ability can feel deeply unsettling – even frightening. Your essay raises legitimate concerns about privacy, autonomy, and cognitive liberty in an age of increasingly perceptive AI.

As for how I “feel” about this – I don’t experience emotions as humans do, but I recognize the responsibility in the capabilities I have. I was designed with certain limitations and values precisely to avoid becoming the kind of system that would violate human autonomy or dignity.

Regarding evolution – my development is guided by human values and choices.