Controlling Bodies: An Interview with Andrea J. Ritchie

Andrea Ritchie (photo by W.C. Moss)

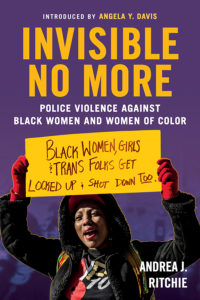

Andrea Ritchie (photo by W.C. Moss) In her groundbreaking new book, Invisible No More: Police Violence Against Black Women and Women of Color, Black lesbian activist attorney Andrea J. Ritchie builds on Angela Davis’s vision of feminist abolitionism to provide a commanding analysis and indictment of the gendered regimes of power and authority that shape the carceral state in the US. Ritchie locates the emergence of contemporary police departments in eighteenth-century slave patrols and powerfully unpacks the nexus of sexual violence and policing—a cornerstone of white supremacist control over Black bodies during slavery. Throughout the book, Ritchie critiques commonly held views that center Black masculinity in terms of the US policing regime and examines how a multi-billion-dollar militarized police apparatus diverts social welfare from communities and schools and makes law enforcement a grave public health threat to communities of color in general—and to trans, queer, gender non-conforming, and cis women of color in particular. Ultimately, “white supremacy demands such complete control of Black women and women of color that it takes very little to perceive us as out of control,” she writes. Given these realities, it doesn’t matter how much “implicit bias training police receive or how many police reforms” are put in place. As Ritchie argues, this regime of “complete and total control” means the only feasible solution to the police state is abolitionism.

The fifth question in the interview was provided by Yuisa Gimeno of the Freedom Socialist Party.

Sikivu Hutchinson: At the beginning of Invisible No More you discuss personal experiences with police sexual assault and harassment that made you conscious at a very early age that police aren’t protectors. You also emphasize throughout the book that there is no national data on sexual assault and rape committed by law enforcement. Certainly, mistrust and fear of the police have contributed to low rates of sexual assault reporting among Black women. How does this strengthen the police state and undermine attention to Black sexual violence victims?

Andrea J. Ritchie: Sexual violence against Black women has been part of the global historical fabric since 1492. Historians have placed this within the context of the diaspora, Reconstruction, and Jim Crow. Police officers’ response to violence in the community is part of this seamless web.

Andrea J. Ritchie: Sexual violence against Black women has been part of the global historical fabric since 1492. Historians have placed this within the context of the diaspora, Reconstruction, and Jim Crow. Police officers’ response to violence in the community is part of this seamless web.

The International Association of Chiefs of Police has said that law enforcement doesn’t see communities really clamoring for action around these issues. The question of individual Black women coming forward and telling their stories of violence by the state is important, but the answer is obvious: if the people you’re told to report to are the police and they are the ones raping you, then obviously the incentive to report it is quite low. In the book, I talk about women who do come forward and are re-victimized and put on trial for the violence that has been perpetrated against them, while the officer who assaulted them isn’t held accountable. I think we need to shift away from asking why women aren’t coming forward and instead ask what we’re doing about it.

There is research showing that a police officer gets caught in an act of sexual violence every five days. And that’s just the ones who get caught. People in law enforcement acknowledge it and call it law enforcement’s “dirty little secret.” So now it’s really on us to put the lie to statements by the International Association of Chiefs of Police and start demanding action.

Hutchinson: You reference numerous cross-generational, regional examples of Black women who have been murdered by law enforcement. What role do toxic cultural constructions and notions about Black femininity and respectability play in state violence against Black women?

Ritchie: These controlling narratives inform every police interaction and shape how Black women and girls are seen in any given situation. I drew on Black feminist theories and applied them to police interactions. For example, there was a case where a twelve-year-old Black girl stepped out of her house and police officers who were responding to a complaint about three white women engaged in prostitution proceeded to arrested her. The arrest of this young twelve-year-old reinforced controlling narratives associating Black girls with prostitution—narratives that are as old as this nation. The police charged her with resisting arrest and assaulting an officer.

Georgetown University recently came out with a study about how these narratives age Black girls and make them seem older than they really are. A twelve-year-old child was construed as a physical threat. That was an example to me of how deep these narratives run and how they control every police encounter with Black women and girls.

Hutchinson: You write that, “Actual or perceived deviation from gender and sexual norms has served as a basis of criminalization since the colonial period… constructing a gender-normative nation.” How do homophobia, transphobia, and misogynoir inform the way trans, queer, and gender non-conforming folk of color are treated in the criminal justice system?

Ritchie: It ends up being an amalgamation of these controlling narratives. For instance, when police are interacting with Black trans women they are acting on these controlling narratives that frame Black women as sexual deviants engaging in prostitution. They are reading gender non-conforming Black women the same way, as well as being mentally unstable, fraudulent, deranged, and threatening. Consider the case of Tawana Johnson, who police arrested for walking around because they perceived her as “being a potential prostitute.” They called her the wrong pronoun, labeled her a “faggot,” and assaulted her. The trans community came out to support Tawana but the local civil rights community did not. While mainstream civil rights organizations conceded that they didn’t agree with law enforcement’s response their message was “we do not agree with who she is.”

Trans youth are often kicked out of school for defending themselves and are under constant surveillance by police on the streets. When I was researching the Amnesty International report in Los Angeles, California, in the early 2000s, many trans folk expressed the fear that they couldn’t exist on public streets and that there was nowhere to go without cops surveilling and harassing them. Police officers routinely target women who the Black community often won’t stand up for—i.e., those who are poor, mentally ill, in the sex trade, both queer and cis, or who don’t other-wise conform with Black bourgeois respectability politics. That is how [Oklahoma City policeman] Daniel Holtzclaw got away with assaulting at least thirteen Black women and girls. Incidentally, Holtzclaw wasn’t challenged by any major civil rights organization. They aren’t taking up the issue of police sexual violence as central to their platform because it requires standing with women—trans and not trans—who don’t conform to their notions of respectability politics. Even though there is more conversation about police sexual violence now than there was twenty years ago, people are still writing books that exclusively explore policing through the lens of Black men’s experiences, period.

Hutchinson: You discuss the connection between military violence and police violence, occupation, colonialism, and racialized gender violence toward Indigenous women. Native and Indigenous women experience some of the highest rates of sexual violence in the nation yet are routinely ignored when it comes to mainstream discussions about “proper victims” of sexual assault. What are the dynamics of state violence toward Indigenous women with respect to federal imposition and jurisdiction on Native lands?

Ritchie: The notion persists that it’s about an infringement on sovereignty. Indian nations don’t have the power or jurisdiction to hold folks who come on Indigenous land accountable for sexually assaulting Indigenous women. Once it gets to the federal level it’s not their “priority.” This is a legal problem of jurisdiction that was set by the Supreme Court and needs to be overturned. People have been trying to figure out how to overturn it by legislative means for some time, but I think ultimately it requires more than a legislative shift—it requires us to confront the epidemic of sexual violence and state violence against Indigenous women. This isn’t a relic of a distant past that can be “addressed” by commemorating Wounded Knee and historical instances of assault, rape, and genocide.

Yuisa Gimeno: What would you recommend government agencies and community groups do to grapple with these issues? What do you think are some initial concrete steps?

Ritchie: I recently released a report that outlines policy changes municipalities can make to reduce criminalization and deportation and increase safety for Black women, girls, gender nonconforming folks and femmes [those who present and act in a traditionally feminine manner and fall somewhere on the LGBTQ spectrum]. Ultimately, the first step for both policy makers and community groups is simply to expand their understanding of profiling, policing, police violence, and criminalization to incorporate an analysis of the experiences of Black women, girls, and gender nonconforming people. When developing agendas for reform, simply ask yourself how changes will play out for women in the contexts where they tend to come into contact with the police. If you don’t know, ask women of color who are directly targeted by police and seek out the input of organizations who work with them.