Honoring the Secular Spiritual Legacy of Groundlings Founder Gary Austin

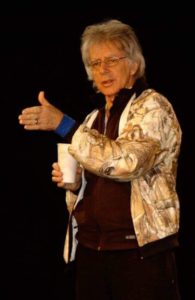

When I heard the news that improvisational theater director, writer, and director Gary Austin died on April Fool’s Day, I thought it was a cruel joke. While I knew Austin had cancer, when I studied with him in Seattle back in October, I assumed we’d continue our work on the two book projects we were improvising together. But this was no joke—the man I had studied with since 1996 was gone.

In the collective reminiscing of those in New York City, Los Angeles, Seattle and elsewhere who call the Gary Austin Workshops their community, his spirit remains present in us and in our work. For those of you who don’t think you’re familiar with his work, if you’ve watched Saturday Night Live over the years (Lorraine Newman and Phil Hartman were both his students), you have. If you remember Pee Wee Herman (a character born when Austin offered Paul Reubens a suit he used for interviews) or Helen Hunt’s As Good As it Gets Oscar acceptance speech in 1997 (she thanked him), you do. Austin’s influence is part of our comedic consciousness.

In a piece I penned for Killing the Buddha in 2013, I interviewed Austin about the connection between his improvisational practices—that move us out of our heads and into our bodies—and the beliefs of atheism, which many artists (including him) espouse. I spoke with him about religion, reason, and comedy, and his answers surprised me.

Becky Garrison: As the founder of The Groundlings, home to many internationally known comedians, why do you call what you do improvisation and not improv comedy?

Gary Austin: Most people who do improv do it for laughs, and it comes off in a very shallow way. I do theater, and most improv is not theater. For me it’s about the process of making discoveries. If I touch the audience, it’s theater, regardless if I make them laugh or not.

Garrison: One of your mantras is that you can make meaning without making sense.

Austin: If I try to make sense, then I will make boring, predictable sense. But if I make choices that don’t make sense to me, I will make sense that surprises me. I trust that the audience is smart, and they can make connections that justify the nonsense.

Garrison: You sound a bit like fellow Texan Bill Hicks when he said, “The voice of reason is in us all…and everyone can recognize it because it makes sense and everyone benefits from it equally.”

Austin: This comes out of living in the moment. I always had a problem as a stand-up comedian because I never tried to make them laugh. In my shows, I’d sing songs and tell true stories that would get tons of laughs. My favorite comedians are [those who] always told the truth. For example, Lenny Bruce saw a hypocritical society and he wanted to expose it. He created pieces that exposed this hypocrisy in the way that Jesus did, which is to tell parables. If you got it, you got it, if you didn’t, then you didn’t.

Garrison: Why is it important to force students out of their heads?

Austin: When you’re in your head, you’re making the sense that you already know about and that you already understand. When I’m in my body, my body is telling me what the sense is. Then I understand the sense. It’s as if God gave me the sense that I come up with. And this sense means something different to every person.

Garrison: You mentioned God. I thought you were an atheist.

Austin: I’m not talking about God as this vengeful father figure. It’s more, there’s something outside of me. I don’t know stuff and I’m OK with that. When I die, as the Bible says, now I see through a glass darkly. So it’s possible there will come a time after my demise when I’ll go, “Oh that’s what that is.” But I know it’s not going to happen while I’m still here.

Garrison: Is improvisation a playful way to seek out the truth in serious topics like religion and atheism?

Austin: I don’t have goals to explore topics when I do improvisation. The only one truth I understand when I improvise is the truth of the moment. Viola Spolin called it the eternal moment. It’s the most spiritual place I can be in.… I’m aware of everything in my skin and outside my skin. I’m aware of my breath, everyone around me, and my environment…. I don’t have a sense of the whole. The audience always sees the whole.

Garrison: How did your one-man show “Church” come about?

Austin: It was really simple. I needed to tell people this story. Things happened when I was a kid growing up in the Nazarene Church in Texas and California that I have to tell people about. It’s an obsession. Let’s say you saw a crime. You would need to tell people about that. The same thing happens with me when I teach. I tell stories that relate to what’s going on in the class. I have to tell these stories at the risk of some people becoming impatient because they think I’m telling stories and not teaching them. But if they stick around long enough, they’ll get the connection.

Garrison: You’ve been through serious health crises, including cancer and heart disease. How have these informed your work?

Austin: My status quo is being maintained and I’m taking medication. Being so close to death reminds me that I’m sick and tired of discovering that I don’t want to work with a particular person. My wife, Wendy, is a much better judge of people. When she says someone is poison, she’s almost always right. I want to work with people where I’m forming connections that pay off.

Garrison: So how do you form spiritual connections when doing your work as an improvisor?

Austin: It’s about empathy. I must have absolute empathy for my partner onstage, regardless of the character he’s playing, his behavior or his point of view. That doesn’t mean I have to condone who he the character is and what he says and does, but I must empathize. Just as important as having empathy for his character, I must have empathy for him the person and artist. That doesn’t mean I have to like him personally. I did a tender love scene with an actress for [the comedy group] The Committee. The scene was in the show for at least a year. We were like Julie and David Eisenhower and I was going off to war. It was our good-bye. I didn’t like this actor on a personal level, and I assume she couldn’t bear me. But the empathy for each other was there, even personally, while we were doing the scene.

As an animal-rights advocate, my empathy for animals who are unable to defend themselves against the barbarism of [human beings] feels much the same as my empathy onstage. Everything I say here regarding improvisation applies to my work as an actor (with written text), a teacher, a director, and a writer. As a concert performer, my empathy for the audience must be foremost in my awareness as I focus on the tasks at hand.

Those wanting to pay tribute to Gary Austin’s work can visit the You Caring page established in his honor.