Humanist EDge: New Children’s Book Celebrates Thirtieth Anniversary of the ADA

Jennifer Keelan-Chaffins, diagnosed with cerebral palsy two years after she was born, was the youngest participant of the Capitol Crawl, a public demonstration held in Washington, DC, on March 12, 1990, to convince lawmakers to pass the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

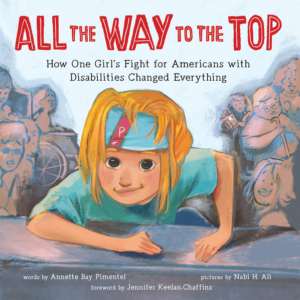

Although the ADA was passed and signed into law on July 26, 1990, Keelan-Chaffins and other people with disabilities continue to fight for their rights and have their voices heard. Her story is spreading with a new children’s book, All the Way to the Top, written by Annette Bay Pimentel and illustrated by Nabi H. Ali, and a statue of her called All the Way to Freedom by Denver sculptor Gina Klawitter.

I talked with Bay Pimentel, Keelan-Chaffins, and her mother Cynthia Keelan this week ahead of the thirtieth anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Emily Newman: How did you learn about and connect with the disability rights movement?

Jennifer Keelan-Chaffins: I joined the disability rights movement at the age of six in 1987 when ADAPT National came to Phoenix, Arizona, to protest the lack of wheelchair-accessible city buses. A family member, who was a disability rights photographer, stayed with us when we lived in Phoenix and invited us to join the protest to get lifts on buses. Let’s just say that by the end of the weekend I was leading a march through downtown Phoenix.

The Capitol Crawl in 1987

Newman: The timeline at the end of the book notes that the year after your first protest in Phoenix, you got arrested during a Montreal protest at age seven, and then at age eight you participated in the Capitol Crawl (the climax of the book).

Keelan-Chaffins: Yes, by the time I did the Capitol Crawl I was a seasoned activist. We pretty much did a protest every four to six months. When I joined the movement, this was the first time that I had seen adults with all kinds of disabilities; there were people in wheelchairs and deaf and blind people. I was empowered watching all these adults fight for their rights. I watched them closely and learned from them. I realized I didn’t have to go to the segregated school, I could go to the neighborhood school with all of my other able-bodied peers.

Annette Bay Pimentel: One thing that struck me as I was learning about Jennifer’s story is that she was put into a specific preschool and other school options exclusively with kids with disabilities, but those were always run by people who did not have disabilities. It was really remarkable at this moment to see people with disabilities be the leaders and take charge in making the decisions.

Newman: That must’ve been especially encouraging after having dealt with medical professionals not giving you much needed support and optimism about your abilities.

Keelan-Chaffins: In the 1980s my family was actually told that I should be put in a children’s home because that would be the best place for me. I grew up with a very supportive family, and my grandfather and my mom basically told the medical professionals “we know what’s best for Jennifer and we’re going to do everything we can to give her as normal a life as possible.” They would adapt my environment instead of making me fit the environment, so that would mean adapting my tricycle so I could ride a bike and putting me on a horse for horseback riding therapy.

Newman: As portrayed in the book, I was saddened at how disrespectful some of your schools were. They not only limited your access to everyday activities, but they also allowed students to bully you.

Jennifer Keelan-Chaffins

Keelan-Chaffins: I will be honest, school was tough. I did face a lot of discrimination but I also had points of support and empowerment. At one school system I had support from the school and my teachers and I was able to completely integrate. They actually changed the classroom from the second floor to the first floor, and I had assistive technology in the classroom as well as a stair climber because the building didn’t have an elevator. When I was ten years old, Governor [Roy] Romer [of Colorado] had introduced a school-of-choice bill. But he excluded kids with disabilities, so I confronted him along with fifty of my disabled friends and basically told him: “You either need to include kids with disabilities in the bill or you need to veto it because it’s an act of discrimination.” By this time the ADA had already been in place for a year, so the bill was a violation of the ADA, and that’s why I confronted him about it. As a result, he did not sign the bill. I was pretty proud of that, and I got to go to my neighborhood school with my sister.

Newman: Are you working with schools to get this book into classrooms?

Keelan-Chaffins: Yes, as a matter of fact, I’ve been working with the Fairfax County school system in Virginia and they’re in the process of using it in their social studies and civil rights curriculum, in the section about disability rights. Right now the book is being used in all twenty-nine middle schools in the county.

Bay Pimentel: Our book was chosen by the Junior Library Guild and was selected by the National Council of Teachers of English to present at their conference. A teacher I met at a social studies conference also made an educators’ guidebook for free.

Before the shutdown started, we did a week of visits to elementary schools in the Denver, Colorado, area and we had really sweet reactions from kids with and without disabilities. Many children would raise their hands not to ask a question but to share with Jennifer their experience with a friend or a family member who had a disability. There’s a part in the story when the girls in the class say “you’ll never be one of us,” and there’s always a really strong reaction in the student body. At one school, a little girl came up to Jennifer afterward and told her that if she were there she would have said “you can be my friend.” I’m glad that kids are embracing this, whether they have disabilities or not. I think the point of the book is that this is an us story, not a them story. This is a story about the disability rights movement but also a story about the power of children.

Keelan-Chaffins: And the power of children’s voices. All it takes is one voice to create change. You don’t have to be a grown up to do that, anyone at any age can create change.

Newman: Over your years as an activist, how have you seen the culture shift for the disability rights movement?

Keelan-Chaffins: Discussing these things today, it’s more open and it’s more out there but I do think that just because the ADA exists doesn’t necessarily mean that discriminatory practices haven’t continued. Finding affordable, accessible housing for people with disabilities has been a big issue over the years, and I’ve noticed new construction where ADA features aren’t always being put into place. While the ADA has advanced physical access, I think one of the things that we still need to work on are those attitudinal barriers that people with disabilities still face today.

Annette Bay Pimentel

Bay Pimentel: From K-12, I didn’t go to school with kids with disabilities, but my children all did. In college I was doing a performance with a woman in a wheelchair and it was like I had never seen our campus before. I would start to go one way and she would say “we can’t go that way because of the stairs or the curb.” I thought about that a lot in later years as I watched the news coverage about the passage of the ADA and I think that personal connection was what kept me interested and noticing what was happening in my neighborhood.

Keelan-Chaffins: First and foremost, the ADA is a civil rights law for people with disabilities and what makes it important is that it’s a law that recognizes us, people with disabilities, as a protected class and recognizes that we have civil rights and the right to be treated like everybody else. That means the right to have access to public spaces, the right to employment, the right to education, the right to vote. One of the things I always grew up with and what I was taught was that this was our Emancipation Proclamation. It’s important to be able to teach the next generation the importance of the ADA, the disability rights movement, and the Capitol Crawl and what it took to get us there, which is why I think the book is so important.

Newman: COVID-19 is exposing ongoing injustices in our society and causing new challenges related to how we vote and how we educate our children safely. How has COVID-19 impacted people with disabilities?

Keelan-Chaffins: This is something that the disability rights community is watching very closely because we’ve seen rights being taken away and we’ve seen COVID being used as a mechanism to take those rights away. It’s against the ADA to deny someone treatment because they have a disability, but we’ve noticed that the medical community is actually using COVID as a way to deny treatment for people with disabilities.

Cynthia Keelan (Jennifer’s mother): Here in Colorado, they were saying that the safest place for people with disabilities were assisted living and nursing centers, yet those places saw the highest reported cases and deaths from COVID. If Jennifer has an asthma attack or something related to her implant, we’ve already had the discussion with the doctors to make sure they take her to the proper place. You have to make sure that they understand that you have a medical directive and a medical power of attorney that says “save my life.” A lot of medical people will just assume people with disabilities have a DNR [Do Not Resuscitate].

Keelan-Chaffins: This is one of the reasons it’s imperative, especially during this COVID crisis, that people with disabilities not be afraid to make sure their needs are heard and are met. And if they’re not being met to say, “I want this particular plan of care and you’re going to give it to me because this is my right, and if you deny me this care it’s a violation of the ADA and I’m not afraid to sue you.” This is why it’s extremely important for advocacy to continue, because if we’re forced to go to the assisted living centers, have respirators taken away, and are denied care, things can get really, really scary.

Newman: COVID-19 and the issues it causes makes the thirtieth anniversary of the ADA this coming Sunday (July 26) so much more important, and the need for it to be understood, practiced and enforced.

Keelan: Disability is a normal part of the human process. When children learn that at an early age, then they’re not afraid and they see the purpose in having the ramp or the Braille panel. At the school where Jennifer had a good experience, there was always somebody there to assist and she was always treated as an equal. Her needs were just accepted as part of the environment instead of being viewed as some weird medical thing. That comes through in All the Way to the Top, and the children we visited before COVID shut things down seemed to pick up on that. We look forward to visiting more schools after COVID and we’re getting good at Zoom now.

Bay Pimentel: I’d like to suggest to families that reading books about people from marginalized groups is a great way to build empathy and to understand, or maybe to find, an issue that you care about and build empathy with people you think are different from you but you may have a lot in common with.

Keelan-Chaffins: For me, the really cool thing about the Capitol Crawl was that all these disability rights groups came together and we had a unified voice and a unified goal to create change. I think that we need to go back to that because there is more work that needs to be done. As a young child who got to be so closely involved in this movement, I realized that I had a responsibility to not just represent myself and my generation but future generations of children with disabilities. I wanted to make sure that their voices were heard just as loud as mine.