Morality, Religion and Bullsh*t: An Interview with Penn Jillette

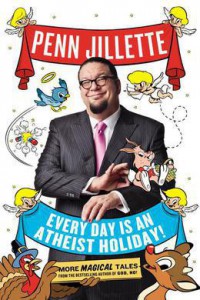

Penn Jillette is the vocal half of the magic duo Penn & Teller, and in recent years the two have won praise by using magic and humor to promote rationalism. Besides his career with Teller, Penn is a popular speaker and writer in the skeptic movement. His new book, Every Day is an Atheist Holiday, explores his love of family and life without religion in often humorous and sometimes tragic stories. In this interview, Penn explains his views on religion, death, libertarianism, retirement, and how an atheist can hold things sacred. Additionally, Penn discusses his work on a forthcoming biography about his mentor James Randi and why he is unlikely to become the voice for any organization.

Ryan Shaffer: You grew up in a family that went to church, even personally mowing the church’s lawn. How did you switch from Christian to atheist?

Penn: By reading the Bible. I was sixteen and part of the youth group with a pastor who was smart, well-educated and wonderful. I was really interested, as one should be, about religion and read the Bible cover to cover from “In the beginning” right up through the craziness of Revelations. While reading I was appalled by the contradictions. I was appalled by the anti-humanness of it and bothered by the stuff like God telling Abraham to kill his son. That kind of test from a God just seemed to be insane and wrong. I’m not sure I was aware of all this at age sixteen, but it continues in the New Testament with Jesus saying leave your family behind and follow me. There’s a whole anti-family thing, a pro-slavery thing, a pro-rape and a pro-killing aspect.

I finished reading the Bible and told my pastor I was an atheist. The pastor was hip enough to keep me in the youth group for about a year until he finally told my parents, “Your son is doing a better job at turning the children atheist than I am at turning them Christian so you can stop coming to church.” I got that reprieve and began referring to myself as an atheist at about sixteen years old, and now it’s been forty years that I’ve been an out of the closet atheist.

Shaffer: Were there any family or social pressures to still conform to religion even though you didn’t believe?

Penn: Not too much. I’m from New England. My parents were older, and had a live and let live philosophy. My mom finally admitted she was an atheist when she was over eighty years old. My sister and nephews became atheists. My father spent his whole life as a Christian and died as a Christian. Although we discussed it and disagreed on it, he never pressured me outside of just talking about it. But that’s not the type of pressure you mean.

As for pressure in society, anyone who is an atheist or humanist knows that the President of the United States says “God bless the USA” and “God bless America,” which can be a little annoying and seen as pressure. But a lot of times, I’m given credit that I don’t deserve. People talk about how brave I am at being an out of the closet atheist and I always tell them that as I get more open about my beliefs, I’ve been more successful. While correlation is not causation, I certainly haven’t been punished for being an atheist. I’ve been very fortunate that way and I know other people have been punished, but I haven’t so there is no real bravery for me.

Shaffer: You’ve said previously that some of your family members became atheists later in life with your influence. How did you get your family to change their minds about religion?

Penn: I don’t know if I did, but I just got them to be more open. I don’t really take credit for that. One of the things that is kind of a contradiction about me is that I’m really in favor of proselytizing. I’m in favor of people who believe anything talking about it with the market place of ideas. At the same time, I don’t believe the motive for talking should be changing minds.

There’s always this thing in the skeptic and atheist movements where some dipshit gets on stage and says: “here’s how to talk to religious people,” “here’s how to make your point,” or “here’s how to change minds.” It’s always said by someone who couldn’t get laid in a women’s prison with a fist full of pardons, and who isn’t good at convincing anyone of anything. It’s always said by a dipshit who is incredibly condescending to both sides by telling atheists there is a way to talk to people other than with their hearts. It is also incredibly condescending to the religious by saying there is some magic button or chess move that you automatically win and they are brought over to the atheist side. I find that disgusting.

Any statement like “how to pick up girls” or “how not to pick up girls” is very insulting to humanity. I believe you should state what you believe in your own style. If you are an aggressive asshole then be an aggressive asshole or if you are mild and gentle when you speak then be mild and gentle. One of the great things about the gay movement with gays coming out of the closet was you had flamboyant queens dancing in G-strings, and also had lawyers and doctors who were much more in the norm.

I think that’s very important for atheists that we just be ourselves and speak from our heart. You always have to know when you’re in a conversation with a Christian that they may convince you and you might change. I was very much changed in my politics by people who argued with me. I try to change my mind on a lot of things and I just don’t think there is a magic bullet or even want a magic bullet to convince people.

So what I did was I lived my life honestly and openly, and loved my family tremendously. Then over time my mom and my sister agreed with me, and my dad didn’t. That has nothing to do with any magical things that I said or anything to do with loving my father. I certainly loved my father completely and unconditionally, and he loved me completely and unconditionally. We just simply disagreed and that’s okay.

Shaffer: The first chapter of Every Day is an Atheist Holiday seeks to address a misconception about atheists, specifically, that atheists don’t keep things “holy” like the religious do. Why do you think religious people are surprised to find atheists do hold things sacred?

Penn: Somehow the religious have grabbed the moral high ground on so many issues that they do not deserve. Every atheist I know has a huge loyalty, and love for family and friends. The religious often think the way they are loving people is by loving God because there has to be a middle man. When Jesus says over and over again drop your family and follow me, and I bring that up to the religious, they often say “It is through loving God that I love my family.”

There are many religious people who are surprised that one of my beefs with religion is how anti-family and anti-family values it is. I also think a lot of religious people are surprised that morality and love are more important to atheists than they are to the religious.

Shaffer: You described the religious view of death as scary and the atheist view as not. Why would immortal life in heaven be scary?

Penn: I find it scary because of our lack of understanding. They brag that what they’re talking about is nonsense and that we can’t quite understand it because it is so far beyond us. The idea that there is an omniscient, omnipresent and omnipotent power that chose to make my mother suffer and die, and chose to fill me with grief is really scary and unpleasant.

The idea that there is an afterlife and this is sort of a torturous, unpleasant test on Earth is scary to me. Whereas the atheist view that “every day is an atheist holiday” and that there is a wonderful celestial lottery that we all won, the comparison that Richard Dawkins makes, that being here is so devastatingly improbable and we can celebrate that along with all the beauty, love and art that is here for us to enjoy. The scary thing is not that we’ll miss an afterlife, but we’ll miss parts of life.

Shaffer: You were diagnosed with cholesteatoma, which potentially could have killed you. During this period did you ever reconsider your beliefs or hope for an afterlife?

Penn: No. It’s really funny, a lot of religious people I know when my mom and dad were alive would say, “You’re an atheist now, but wait until your mom and dad die, wait until you really suffer.” It’s this weird belief that when there’s enough fear you’ll be like us, which is a very weak argument.

The times I’ve been close to death, had guns pulled on me or been really sick in operating rooms, I haven’t felt what Paul Kurtz called the transcendental seduction. I haven’t felt that at all. I have felt a type of bargaining where I talk to myself about getting through something and I’ll be different. But I’ve always perceived that as a thought process and not a prayer. That’s the difficult thing about the definition of prayer. If you used to be, like it is to some Muslims now, a time, specific place and way to talk to God. The modern Christians have made that such a liberal definition that talking to oneself becomes, in their mind, a form of prayer. I do talk to myself thinking things out and I bet that would feel to some people like praying and desperation, but it doesn’t seem like that to me.

There are some people who argue that the real secret to religion, which I think Steven Pinker made, is consciousness. Once you have a sense of self, you have a sense of floating above the world as a type of third-person memory. It is possible that way with a feeling, but it is not a crying out to God. Rather, it is just a talking to myself.

Shaffer: You write that a few of your opinions made on Bullshit have changed since the show. Which ones?

Penn: Some information has changed. When we did the secondhand smoke episode our point was that it wasn’t the government’s business to legislate and by the way the secondhand smoke studies weren’t really there. The secondhand smoke studies are there for people living in households, but they are much looser on someone smoking in a workplace down the hall affecting everyone. However, it’s still stronger science than it was when we said it. The information changed and with the information changing I would like to change myself.

The other issue is global warming, which we never addressed contrary to public opinion. Everyone seems to think we did a global warming episode on Bullshit where we were skeptical of global warming. Well, that never happened. There were asides during other topics, like the ecology or Earth Day parts. Although I used to be more skeptical it seems like the information, and by that I do not mean Hurricane Sandy, but the preponderance of information seems to be there is climate change and it is anthropogenic. Although I still don’t know that the best solution is just a stronger government.

What’s so odd is that when we have tragedies like 9/11 many people use that tragedy to say, “We need a stronger government and more draconian laws.” For climate change, there is the idea that there is a horrible emergency so we need a stronger government and more draconian laws. I wish we would at least consider, when given a tragedy or emergency, the idea of trying to solve it with more freedom instead of less.

Shaffer: In God, No, you close the book by writing “atheism is the only real hope against terrorism.” There are many motivating factors behind terrorism, including socio-economic conditions and political reasons. The Red Brigades, for example, went on a terror spree in Italy even killing the former Prime Minister in 1978 to bring about a communist revolution. Is there any difference between faith in a political ideology like Marxism and faith in religion?

Penn: Yes, there are certainly differences. I don’t want to fall into the trap of doing mental gymnastics to make my position make sense. The very word “faith” as it is used by the religious is the idea of believing something without evidence. If you have evidence there is no faith required.

On communism, or as you called it “political faith,” I’d have to see the specific situation to know if the person thought that following those rules of politics did not have to be supported by evidence. What I mean specifically by faith is that it is not supported by evidence. I was not saying, or I should not have said if it read that way, all bad things are caused by religion or all terrorism is caused by religion. But certainly, embracing the idea that you should believe things without evidence destroys all chance of talking sense to someone who is planning something dangerous.

If you write in a Facebook discussion that you believe in an overwhelming spirit in the world, not from any evidence, but just from what you feel in your heart then the second you type that you have automatically condoned Charlie Manson. If you can believe in your heart something that you have no evidence for then why can’t Charlie Manson believe in his heart that he’s Jesus Christ and Sharon Tate should be slaughtered by people in his “family”? Once you’ve condoned believing things without evidence you have opened the door to insanity. You have said to anybody that if there’s a strong feeling in their heart they can’t back off.

When I feel faith, I try to fight against it. When I think that I believe something because I want to believe it because it feels right I try to be skeptical of that. Now as soon as I say that, I will also say I’m unsuccessful. There are many beliefs I have that are not supported, but I’m trying to fix that. I like to think that’s a tiny step towards doing the right thing.

Shaffer: As you’ve pointed out, you are neither on the collective left nor the right. Some liberal atheists disagree with your politics and some conservative libertarians disagree with your social views. Is there any connection between your atheism and libertarianism, or are they completely separate?

Penn: To me, they are part of my personality and both of them come from my optimism as well as a kind of happiness, confidence and support from people I know and love. Being libertarian, emotionally, requires a kind of sunny outlook that people will take care of each other. It stems from really strong community ties.

Atheism, I sometimes worry, that like the religious gaining the moral high ground they also take the love high ground. It seems backwards. I have so much love in my life. So many people who love me and I love back makes the idea I need more from a God insane. I look at my children and I’m overwhelmed with this pure love that is not filtered through any sort of God. I think that kind of support and love in my life has led me both towards libertarianism and atheism. However, it would be insistent of me to think those are linked for everyone.

I know some people believe in a libertarianism that’s pretty harsh. Those people are not thinking it is coming from how much we love each other and can help each other through freedom, but comes from a view that people who don’t work hard enough should in some way be punished. I never consider that, but it is certainly part of libertarianism. I also know there are atheists who are bitter and became atheists not because there is so much love in the world, but with the idea that there is so much pain and suffering how can there possibly be a God.

You can feel the love of life and not need a God in the beauty of a sunset, but you can also see an absence of God looking at Auschwitz. Everything I have on these things tends to be very Pollyanna. I love every day, have a great time and great friends. It doesn’t feel correct for me to say that everybody would connect those two things. I know many atheists that are not libertarian and I know many libertarians that aren’t atheists. So to say they are connected would be contrary to fact, but in my heart they are linked.

Shaffer: That’s one of the things I am curious about your libertarianism. You’ve written that you don’t want the government involved in education or funding research to cure cancer. Do you believe society should have law enforcement, fire departments, national defense or a court system paid for with taxes?

Penn: Absolutely. I believe there are legitimate purposes of the government like defense, courts and police. I don’t think you can privatize police, jails or courts. That’s where legitimate force comes in. My question is: What would I personally use a gun to accomplish? I would use a gun to stop a rape. I would use a gun to stop a terrorist attack. I would not use a gun to build a library. My morality is such that if I’m not willing to use violence myself, I’d never use violence because I’m a coward, but theoretically if I’m not willing to use violence myself then I can’t condone the government using violence.

You end up having to draw a line somewhere. I just draw the line towards more freedom. It’s a difference between medicine that’s covered by insurance and lasiks. Lasiks become cheaper and quicker because people are paying for it. We’re seeing with education what’s happening with online college courses. It’s so funny to see Mitt Romney and Barack Obama arguing about how to educate people while the technological solution is happening all around them. They are trying to figure out how to get people in colleges that are hundreds of years old when we have the colleges, in many cases, for free. I know there is an access point where you have to have a computer and Internet, and those access points are non-trivial. Please don’t misunderstand me. Not everyone has a computer and access. Most of the world doesn’t have enough food. But that being said, for the people Romney and Obama are talking about getting the education that solution is there.

My children do go to school, fancy-ass private schools, but I still think most of their education is happening online. So I do think there are private solutions to problems we previously thought were strictly public. I think the solution to education a hundred years ago may have been public schools. The solution a hundred years from now certainly won’t be.

Shaffer: You wrote about religion, in particular Christianity, playing a large role in American politics and rise of non-believers. Do you think the U.S. will have a president in the future who will criticize religion and/or be an atheist?

Penn: Yes I think so, but that is unimportant. If you asked people in 1980 if they would vote for a divorced movie actor as president, none of them would have said yes. They didn’t vote for a divorced movie actor, they voted for Ronald Reagan. If there’s an atheist candidate the public will not be voting for an atheist candidate, but will be voting for the person they consider the best one for the job. That’s often forgotten. I guess if you ask people if they’ll vote for an African American for president they might have an opinion, but we did not elect an African American as president, we elected Barack Obama. That’s such a strong part of my view of individuals that you must judge them as individuals and not as a group they belong to.

Shaffer: You were previously working on a biography about James Randi. Whatever happened to that?

Penn: I’m calling Randi about that tomorrow or today if I get to it. All the research was done. I put in a lot of money and hired many people to do hundreds of hours of interviews about Randi, and lay out the chronology to get everything right. It is now a question of who will actually write it and how it is written. A few people have taken a pass at it and I’m going to talk to Randi about how best it should be done.

The real issue that Randi and I will be talking about is how much we want it to be folksy and pop, and how much we want it to be scholarly. Another way to put it is, how much we want it to be Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman and how much we want it to be Genius. Both are wonderful books about Richard Feynman, but from very different points of view. One is very light and fluffy, and other is really hard-hitting and scholarly with warts and all. I don’t really know which way we’re going to go. Obviously, like Feynman we should do both, but the issue is which one I’m going to be involved in.

Shaffer: Do you have any plans to become more active in the skeptic movement after you retire, like James Randi did?

Penn: I intend to die in office. There won’t be retirement from Penn & Teller. I’m about as involved in the skeptic movement as I can be. I’m a loose cannon and want to be a loose cannon. Every time I speak for anybody, well anybody other than Teller, when I speak for a group I always feel I might fuck up. I don’t want to be the one who says something that’s misunderstood on behalf of skeptics, the JREF (James Randi Educational Foundation) or humanist organizations. I call myself an atheist, but I don’t speak for the American Atheists. That sums it up.

I call myself a skeptic, but I don’t speak for the JREF mostly because I want responsibility for myself and not for a group. There are some people suited to speaking for a group and some people who should speak for themselves. One of the arguments I always had with the JREF was that I thought Randi should always be speaking for himself instead of for an organization. He ended up speaking for an organization and that makes him very happy. I like going off half-cocked and being wrong. But with an organization you can’t really turn around that quickly. I’m very willing to say on live television that “oops, I was wrong” and with an organization I think you should vote on that.

Next Week in HNN: Ryan Shaffer reviews Penn Jillette’s book, Every Day is an Atheist Holiday.