Celebrating Black Humanists: Ernie Chambers

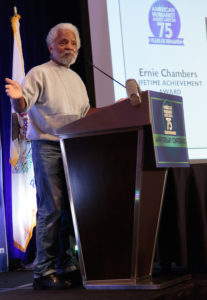

Chambers accepts the Lifetime Achievement Award at the AHA's 75th Anniversary Conference in Chicago on May 28, 2016.

Chambers accepts the Lifetime Achievement Award at the AHA's 75th Anniversary Conference in Chicago on May 28, 2016. In honor of Black History Month, we’ll be profiling an important contemporary Black humanist (or humanist ally) in a different field each week during the month of February. This week, we profile humanist state legislator Ernie Chambers.

Ernest William Chambers left the Nebraska legislature in January 2021 as a result of term limits holding the distinction of being the state’s longest-serving legislator, representing his North Omaha district for 46 years. He was Nebraska’s first Black state senator, the first state senator to be term-limited out of office in 2008, and the first state senator to be term-limited out twice, after he returned to the senate in 2012.

The Omaha World-Herald has called Chambers, “The most famous Black man in Nebraska and one of the state’s most influential figures.”

Born in Omaha in 1937, Chambers was one of seven children. He graduated from Omaha Tech High School in 1955 and obtained a BA in history, with minors in philosophy and Spanish, from Creighton University in 1959. He earned a law degree from Creighton University School of Law in 1975.

An earlier profile of Chambers, written by former Humanist editor-in-chief Jennifer Bardi, said,

After finishing his undergraduate degree, Chambers worked at the Omaha Post Office, where he became frustrated by managers who referred to the African-American staff as “boys.” He complained and later said he was fired for it. Soon after, he landed a job at Goodwin’s Spencer Street Barber Shop. There, Chambers and the owner, Dan Goodwin, held court, dealing with heated issues that affected the black community and created a vital space for activists to learn, vent, and organize. The two appeared in the Oscar-nominated 1966 documentary, A Time for Burning, in which they discussed race relations in Omaha. Tensions arose in the summer of 1966 when black teenagers clashed with police. Chambers emerged as a leader for the community, meeting with the mayor and helping to end the subsequent rioting.

He first ran for the state legislature in 1970 and was elected to represent North Omaha’s 11th District in the Nebraska State Legislature. He championed many causes including abolishing the death penalty, ending corporal punishment in schools, reforming criminal justice and police accountability, affording equal state pensions to women, barring job discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity, and changing to district-based voting to give nonwhite citizens a fair shot at election to public office.

In 1980 he sued to challenge the practice of opening legislative sessions with a prayer led by a state-sponsored chaplain. In 1983 the case went to the US Supreme Court, which unfortunately ruled the practice constitutional. Attempting to bring attention to frivolous lawsuits, Chambers in 2007 sued God for “certain harmful activities and the making of terroristic threats… of grave harm to innumerable persons.”

Brought up going to church, Chambers later moved away from his religious background. He was known for his well-tuned sense of justice, once saying, “I know I am the most feared and most hated man in this state. I know that and it doesn’t mean anything to me because my life is not based on whether people approve of what I do or agree with what I do.’

When he retired, the Omaha World-Herald wrote, “He has stood up for the ‘least, the last and the lost’…. He has been a thorn in the side of opponents and has demanded high standards from public officials. And he continues to inspire generations of Nebraskans to pursue racial justice and equity.”

On May 28, 2016, Chambers was honored with the American Humanist Association’s Lifetime Achievement Award at the AHA’s 75th Annual Conference in Chicago. During that speech, he said

Children try to believe what those they respect say they believe. So, when I was thinking and behaving as a child, I tried to be a Christian, but it was so preposterous to me that I never could be one. But I don’t need religion. I don’t need a heaven to be promised to go to and I don’t need hell to be afraid of to do what I think is right. I do what I believe is right and I don’t care what anybody else says.

An adaptation of his speech was published in the November/December 2016 issue of the Humanist.