Moving from a War Economy to a Peace Economy

Behind every question about how to get the United States back on track and improve the lives of average Americans (the so-called 99 percent) lies the necessity for economic conversion—that is, planning, designing, and implementing a transformation from a war economy to a peace economy. Historically, this is an effort that would include a changeover from military to civilian work in industrial facilities, in laboratories, and at U.S. military bases.

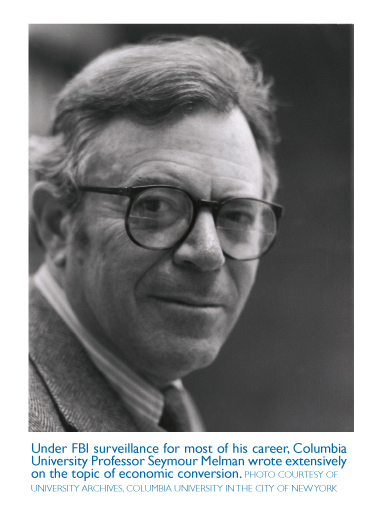

To that end, I am compelled to share what I’ve learned from reading Seymour Melman, the most prolific writer on the topic.

Melman was a professor emeritus of industrial engineering at Columbia University. He joined the Columbia faculty in 1949 and, by all reports, was a popular instructor for over five decades until he retired from teaching in 2003. (He died a year later.)

Melman was a professor emeritus of industrial engineering at Columbia University. He joined the Columbia faculty in 1949 and, by all reports, was a popular instructor for over five decades until he retired from teaching in 2003. (He died a year later.)

Melman was also an active member of the peace movement. He was the co-chair of the Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy (SANE), and the creator and chair of the National Commission for Economic Conversion and Disarmament. It is reported that Melman was under surveillance by the FBI for much of his career because of his work criticizing the military-industrial complex—a sure sign that there must be something worth hearing in his work. What did he say that the power structure feared?

The economic conversion movement in past decades played a valuable role in bringing together the peace movement and union leadership to do the heady work of imaging how this country could sustain industrial jobs when, as it was envisioned, the United States would cease production of the weapons of the Cold War. It is a history that should not be forgotten.

Melman noted that U.S. industry had historically followed an established set of market rules: industry created products consumers needed or wanted, sold those products, made a profit, and then used those profits to improve production by upgrading the tools for more efficient production.

Military production for World War II began to change these rules of industry, which were later institutionalized in the 1960s when Robert McNamara was secretary of defense. McNamara, who came to the Pentagon after his tenure as an executive at Ford Motor Company, implemented some critical changes.

Within the Pentagon, civilian and uniformed officials were in conflict about the procedures for how to determine the costs of weapons to be contracted for manufacturing. On the one side, led by an industrial engineer, the idea was to base costs on the formulation of alternative designs and production methods—a competitive approach that promoted economic growth. The other side proposed generating costs based on what was previously spent. For the Pentagon, this meant following the “cost-plus” system used during World War II, also known as cost maximizing. As Melman put it in his 2001 book, After Capitalism, “contractors could take the previous cost of making a product for the Pentagon and simply add on an agreed-upon profit margin.”

McNamara opted for the second option. The result was that by 1980, the cost of producing major weapons systems had grown at an annual rate of 20 percent. Melman observed that by 1996, the cost of the B-2 bomber exceeded the value of its weight in gold.

McNamara went on to model the Pentagon after a corporate central office, defining policy, appointing chiefs of subordinate units, and maintaining accounting and management functions with huge discretion. Each military service participated in the process of acquiring material and weapons. This process resulted in tens of thousands of employees becoming hundreds of thousands, paid with U.S. tax dollars, to maximize the profits of weapons producers.

Melman minced no words in articulating the consequences in the opening of his book, Pentagon Capitalism (1970) and later in The Demilitarized Society (1989):

The operation of a permanent military economy makes the president the chief executive officer of the state management controlling the largest single block of capital resources…this combination of [economic, political, and military] powers in the same hands has been a feature of statist societies—communist, fascist, and others—where individual rights cannot constrain central rule.

…Nowhere in the constitution is top economic power conferred.

Among the many critical consequences of the state-controlled industry described by Melman in After Capitalism:

- Firms were no longer efficiency-oriented—rather, industry produced increasingly complicated goods.

- Production had nothing to do with meeting the needs of ordinary consumers. Melman pointed out that even though a nuclear-powered submarine is a technological masterpiece, consumers can’t eat it; can’t wear it; can’t ride in it; can’t live in it; and can’t make anything with it.

- Labor lost control of any decision-making it had over production. With the influx of capital came an influx of white-collar middle managers, and the alienation—or disempowering—of workers.

- Where the U.S. was once a top producer and exporter of tools needed for production of consumer goods, the complexity of military production focused industry on specialized machinery and tools that have no utility in meeting consumer needs.

- The Pentagon consumed the talents of U.S. scientists and engineers whose skills were needed in other sectors of society.

In one of Melman’s last articles, published in the political newsletter Counterpunch in March of 2003, his frustration was palpable. He noted that New York City put out a request for a proposal to spend between $3 and $4 billion to replace subway cars. Not a single U.S. company bid on the proposal—in part because the nation no longer had the tools it needed to build its subway trains. In the article, titled “In the Grip of a Permanent War Economy,” Melman calculated that if this manufacturing work were done in the United States, it would have generated, directly and indirectly, about 32,000 jobs. “The production facilities and labor force that could deliver six new subway cars each week could produce 300 cars per year, and thereby provide new replacement cars for the New York subway system in a twenty-year cycle,” Melman wrote, noting that such an endeavor would depend on well-trained engineers but that “it is almost twenty-five years since the last book was published in the United States on [urban public transportation].”

Percolating within the economic conversion movement that began some four decades ago was a vision to reduce the economic decision-making power of the wartime institutions. The plan was to set up a highly decentralized process, based on “alternative-use committees,” to implement the changeover from military to civilian work in factories, laboratories, and military bases. Half of each alternative-use committee would be named by management; the other half by the working people. There would be support of incomes during a changeover.

Percolating within the economic conversion movement that began some four decades ago was a vision to reduce the economic decision-making power of the wartime institutions. The plan was to set up a highly decentralized process, based on “alternative-use committees,” to implement the changeover from military to civilian work in factories, laboratories, and military bases. Half of each alternative-use committee would be named by management; the other half by the working people. There would be support of incomes during a changeover.

Nationally, a commission chaired by the secretary of commerce would publish a manual on local alternative-use planning. It would also encourage federal, state, and local governments to make capital investment plans, creating new markets for the capital goods required for infrastructure repair.

Three principal functions would be served by economic conversion: First, the planning stage would offer assurance to the working people of the war economy that they could have an economic future in a society where war-making was a diminished institution. Second, reversing the process of economic decay in the U.S. economy, particularly in manufacturing, the national commission would be empowered to facilitate planning for capital investments in all aspects of infrastructure by governments of cities, counties, states, and the federal government, which would comprise a massive program of new jobs and new markets. (Melman frequently referred to the annual “report card” published by the American Society of Civil Engineers to highlight the declining U.S. infrastructure—deteriorating roads, bridges, schools, and so on—a situation that continues to worsen.) And third, the national network of alternative-use committees would constitute a gain in decision-making power by all the working people involved.

Melman worked with students, union leaders, the peace movement, and with Congress to create momentum around these ideas. There were some key events along the way.

In 1971, George McGovern included the idea of economic conversion when he announced his candidacy for the Democratic presidential nomination. His statement included this position:

Basing our defense budget on actual needs rather than imaginary fears would lead to savings. Needless war and military waste contribute to the economic crisis not only through inflation, but by the dissipation of labor and resources and in non-productive enterprise…

For too long the taxes of our citizens and revenues desperately needed by our cities and states have been drawn into Washington and wasted on senseless war and unnecessary military gadgets… A major test of the 1970s is the conversion of our economy from the excesses of war to the works of peace. I urgently call for conversion planning to utilize the talent and resources surplus to our military… for modernizing our industrial plants and meeting other peacetime needs.

In 1976, SANE held a conference in New York City titled “The Arms Race and the Economic Crisis.” Melman was a featured speaker. This conference was instrumental in winning an economic conversion plank in the Democratic Party platform that year. A decade later, in 1988 and ’89, Melman had several meetings with then Speaker of the House, Rep. Jim Wright (D-TX). Wright convened a meeting of certain members of Congress who were committed to supporting the economic conversion bill proposed by Rep. Ted Weiss (D-NY). Speaker Wright told Melman that, in his opinion, the arms race had taken on dangerous but also economically damaging characteristics and that military spending “sapped the strength of the whole society.”

On the first day of the opening of the 101st Congress, Speaker Wright convened a meeting of members who had proposed economic conversion legislation, along with their aids. The purpose was to ensure that all proposals be joined into one, and that this legislation be given priority. To dramatize the importance of this bill, it would be given number H.R. 101.

Melman and SANE were elated. And then reality hit. As Melman reported: “Supporters of such an initiative did not reckon with the enormous power of those opposed to any such move toward economic conversion. In the weeks that followed, these vested interests waged a concerted and aggressive campaign in Congress and the national media to bring down Jim Wright over allegations of financial misconduct.”

The allegations had little substance, but Newt Gingrich, representing a headquarters district of Lockheed Martin, led the Republican attack. Sadly, they won. According to Melman, “Their media campaign drowned out any further discussion of economic conversion… A historic opportunity had been destroyed.”

Even so, economic conversion plans were being developed in California and beyond. A 1990 Los Angeles Times article reported that

Irvine, California Mayor Larry Agran planned to make his home town a national model for economic conversion by using what all presumed would be “under-worked” defense companies to build a major monorail project. He envisioned a major local mass-transportation industry. His proposed Irvine Institute for Entrepreneurial Development would also look for ways to push local rocket scientists toward environmental cleanup, healthcare, and other such enterprises.

In Los Angeles, Councilwoman Ruth Galanter, with the support of the International Assn. of Machinists, convened a committee to study prospects for converting aerospace jobs to establishing an electric car-manufacturing industry. They argued that there were linkages in technologies and skills across industries.

On the state level, California Assemblyman Sam Farr promoted a package of bills that required the governor to 1) convene an “economic summit” on conversion, 2) appoint a council to study the issue, and 3) come up with a means of facilitating the transfer of military technology to the civilian sector.

At the federal level, Senator Weiss continued to push economic conversion legislation until his death in 1992. (To my knowledge, no other member of Congress has taken on this issue.) But George H.W. Bush’s attack on Iraq in the 1990 Persian Gulf War was a critical nail in the coffin of the national economic conversion movement.

That’s not to say there haven’t been some in the peace movement who have continued to keep the embers of economic conversion alive. In Groton, Connecticut, for example, the local peace community organized a “listening project” to engage the community about what economic conversion might look like for General Dynamics’ Electric Boat Company, builder of submarines for the U.S. Navy. For more than thirty years, the Peace Economy Project in St. Louis has been advocating for conversion from a military to a more stable peace-based local economy. The Woodstock, New York, peace community held a conference in 2009 focused on the conversion of Ametek/Rotron, a local manufacturer that makes parts used in F-16 fighter planes, Apache attack helicopters, tanks, and missile delivery systems. Certainly there are others out there engaging their home communities in envisioning alternatives to continued production for endless war.

My partner, Bruce Gagnon, is the coordinator of the Global Network Against Weapons and Nuclear Power in Space and has been organizing around conversion since the 1980s. His typical question to any audience is: “What is the United States’ number one industrial export?” Audiences across the country shout out “weapons.” He then asks them to consider that if weapons are the number one industrial export, what is the global marketing strategy? “Endless war” becomes the refrain.

My partner, Bruce Gagnon, is the coordinator of the Global Network Against Weapons and Nuclear Power in Space and has been organizing around conversion since the 1980s. His typical question to any audience is: “What is the United States’ number one industrial export?” Audiences across the country shout out “weapons.” He then asks them to consider that if weapons are the number one industrial export, what is the global marketing strategy? “Endless war” becomes the refrain.

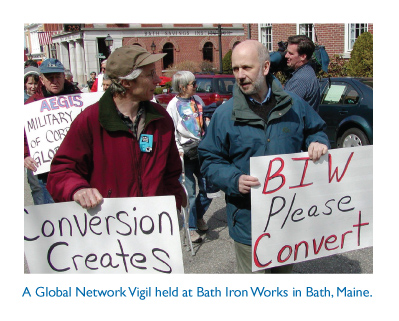

In 2003 Bruce and I moved to Maine, in part to be near Bath Iron Works (BIW), the General Dynamics-owned production facility for naval destroyers that are deployed with Aegis weapons systems. These Aegis destroyers are part of the “Star Wars” or missile defense vision; they rely on space satellites when launched toward their targets. Bruce and I joined the vigils organized by peace groups in Bath, and Bruce organized some vigils for the Global Network. We would hold signs critical of the purpose of the Aegis destroyer (after all, it’s not about defense but destruction) and would offer an alternative vision for the factory (build wind turbines, not destroyers). Initially, people laughed, scoffed, scorned, and some spewed hateful things at us.

In 2007 we bought a big house in Bath with a friend, tore down a wall to create a community room, and began hosting conversations about the idea of economic conversion. We interviewed people who had lived in the community for some time. We interviewed workers at BIW, including Peter Woodruff, who joined our conversion study group early on. Broken-hearted by the role of the Aegis destroyers in the shock and awe campaign on Iraq, he has been a brave and creative organizer inside the shipyard.

As BIW copes with episodic layoffs and a diminishing need for U.S. warships, fewer people scoff at our signs and message. Envisioning a future for BIW in a peace economy is an essential asset to the community.

Meanwhile, there is momentum in Maine to generate wind power options. A professor at the University of Maine is experimenting with composite materials to create a prototype for an offshore wind turbine, and a former governor has created a private company to position wind turbines throughout the state.

As a friend who was an employee at BIW many years ago points out, BIW did convert years ago—from making commercial ships to naval destroyers. Can it experience another conversion now, making wind turbines and other renewable energy products? What if BIW converted to making hospital ships?

The idea of transforming the U.S. military to a humanitarian relief organization is not unheard of; Maine author Kate Braestrup spoke at the state’s Veterans for Peace PTSD conference this year and told the story of her Marine son who has experienced a number of deployments focused on disaster relief. She asked him how he could do humanitarian relief using former instruments of war. He told her it took some creativity, but they were able to transform their equipment to rebuild infrastructure. Braestrup then asked this question: given that devastating extreme weather events will continue to occur, why don’t we build hospital ships at BIW to meet the need for disaster relief—and if we need to adapt the material to fight wars, then certainly we can figure out how to do that, right?

It behooves the peace movement to create a vision that the populace can get excited about—a vision that will capture people’s imagination. A vision that sees the skills and talents of our engineers and scientists creating the renewable energy infrastructure critical to surviving the twenty-first century; a vision that engages peace activists, environmentalists, labor, students, artists, and food security folks in creating plans for how we will warm, feed, and transport people in the year 2040. This is the true security need for the United States, and the world.

Economic conversion is an idea whose time has come. As evidence, I submit that we have an ally in none other than Deepak Chopra, the preeminent leader in the field of mind-body medicine. Few people know that, after the 2008 election, Dr. Chopra sent a public letter to Barack Obama that he called “Nine Steps to Peace for Obama in the New Year.” Asserting that it was an anti-war constituency that elected Obama, Dr. Chopra invoked the spirit of Dwight D. Eisenhower in insisting Obama move from an economy dependent on war-making to a peace-based economy. Dr. Chopra’s recommendations included writing into every defense contract a requirement for a peacetime project; subsidizing conversion of military companies to peaceful uses with tax incentives and direct funding; converting military bases to housing for the poor; phasing out all foreign military bases; and calling a moratorium on future weapons technologies.

The vision is clear, it is obvious, it is mainstream. An important next step for us is to determine what we can do in our home communities to empower local unions and workers, environmentalists, healthcare workers, social workers, secular and spiritual leaders alike, and the neighbors next door to engage—to look around, determine the needs, create the collaborations, and wrestle the funds away to start building a survivable future.