Damned Good Company: Twenty Rebels Who Bucked the God Experts

I came to the humanist movement in the 1970s, not as a refugee or rebel against the abusive teachings of organized religion but as one already born into an atheistic humanist family who was longing for what Luis Granados calls “damned good company.” And I found it. I was attracted by the American Humanist Association’s humanist manifestos, by its open atheistic stance, and most of all by its activism for things I believed in like the separation of church and state and the dignity of every person.

But as time went on I felt that the movement was not fully satisfying me. Something important was missing. It was a feeling for humanism’s connection to our human nature as informed by science and history. To fill this gap I started to read a series of books about what science and history teach us about our human nature. This background enabled me to write The Bible Through the Eyes of Its Authors (iUniverse, 2006) and to design a course, “The Many Faces of Humanism,” which I’ve taught since 2009 and have shared on the AHA’s website.

However I still felt that we lacked a high quality book about humanism’s role in world history that offered the public an engaging perspective in the vein of Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States. Granados evidently had this objective in mind when he wrote Damned Good Company: Twenty Rebels Who Bucked the God Experts, which to my delight turns out to be a damned good book.

Granados researched stories of humanist heroes and heroines from the history of civilization, spanning from fifth-century BCE Confucius and Buddha to twentieth-century Steven Biko and today’s Ayaan Hirsi Ali. You may not recognize all their names but you won’t likely forget them after you read this book. Granados writes with the confidence of an investigative reporter who’s travelled by time machine into each era and locale to interview people and to personally witness the political intrigues, the betrayals of the people’s trust, and the rages of the mobs.

Each of the twenty chapters constructs a character portrait of a lone humanist who struggled against the dark forces of theocracy, superstition, and just plain human nastiness. By evoking an emotional response, Granados educates the reader to the power and vulnerability of humanism in our historical heritage. In fact, his book could easily have been less creatively titled “A Short History of Humanism in the Global Civilization.” While Granados comes down hard on the abuse of religion he does not bash god-belief per se. In the Introduction he writes:

I have no problem with God. I have no problem with the idea that there might be a force our intellect does not understand—and perhaps cannot understand, that was involved with the creation of the universe. The debate about God has raged for a long time. There is nothing new to say about it. So I won’t.

The book’s prime target is the exploitation of people’s superstitious nature by priestly figures, whom Granados labels “God experts.” He reports on mortal combats between humanist heroes and heroines and a nasty series of absolutist God experts who create travesty trials to condemn nonbelievers, heretics, critics, skeptics, so-called witches, and other “rebels,” and who also exhort credulous mobs to violence against them. And yet many of the humanists he depicts also believe in God as the creator and as the grounds for their humanistic ethics within those same religious traditions that the God experts smother. It’s those religious humanists who demanded decency from their society.

What I found frightening is that this dynamic isn’t simply a relic of history but remains an active force in the twenty-first century with few signs of abating. Hence each story from the remote past feels as if it were taking place somewhere in our own world. Perhaps this is because of Granados’ uncanny ability to capture the character of each hero or heroine and contrast with the ugly mood of the God experts; their political powers, trial courts, wealth, and mobs.

Today’s AHA recognizes that many humanists in the world’s religious traditions share a set of core values with our movement, and are often allies in our battles for the separation of church and state. Like us, they seek reason in public discourse for a humane and compassionate civilization. Every humanist portrayed in Damned Good Company, religious or secular (Granados’ selections include men and women from Jewish, Christian, and Islamic civilizations), is abundantly endowed with these values.

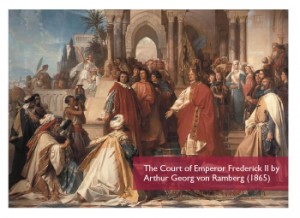

Here’s a sample of how Granados delivers the goods. In a story of a rare humanist ruler in the feudal dark ages, he narrates the amazing career of Frederick II (1194-1250), who was crowned King of Sicily in 1197 at the age of three. In his career he also became King of Germany and Jerusalem, as well as Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. What was amazing was this king’s commitment to humanist values in the face of popes who were offended by his reforms. Frederick’s maternal grandfather, Henry I, who had also been a Holy Roman Emperor and King of Sicily, had previously instituted humanist reforms. Granados reports that Henry I established a tolerant multicultural society where Christians, Jews, and Muslims could enjoy security and protection in the practice of their religious customs.

Here’s a sample of how Granados delivers the goods. In a story of a rare humanist ruler in the feudal dark ages, he narrates the amazing career of Frederick II (1194-1250), who was crowned King of Sicily in 1197 at the age of three. In his career he also became King of Germany and Jerusalem, as well as Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. What was amazing was this king’s commitment to humanist values in the face of popes who were offended by his reforms. Frederick’s maternal grandfather, Henry I, who had also been a Holy Roman Emperor and King of Sicily, had previously instituted humanist reforms. Granados reports that Henry I established a tolerant multicultural society where Christians, Jews, and Muslims could enjoy security and protection in the practice of their religious customs.

When Frederick grew up and assumed the reins of empire, he secured and extended his father’s reforms by abolishing serfdom, stripping clergy of judicial authority in criminal cases, increasing penalties for crimes against women and granting them inheritance rights. He also banned trial by ordeal, by which if a prisoner died in the torture process, it was proof of guilt. He adds that Frederick’s court “enjoyed a golden age that Europe had not witnessed in a thousand years.” In the end a cruel and powerful papal opposition not only extinguished these accomplishments, it also murdered all of Frederick’s sons and other descendants. As Granados wryly comments, “pre-Enlightenment humanist heroes didn’t fare too well.”

While all twenty stories are historically important, Chapter Eleven, “Paine and Talleyrand,” illuminates the role that the French Revolution played in the formative years of our own American republic. Thomas Paine authored The Age of Reason that Granados believes “may be the most profound statement on religion that the world has yet seen.” Yet Paine was no mere writer of books. He was a political activist who took enormous risks. In Paris, Paine had met Benjamin Franklin, who helped him find employment in America in 1776 as a magazine editor. That year Paine anonymously published Common Sense, a pamphlet that supported the American Revolution with great success. In 1787 he returned to England where he published The Rights of Man, attacking the monarchy. But to avoid arrest he fled to France, which was in social disarray. Granados narrates how he somehow joined the anti-Church leadership of the French Revolution and was instrumental in drafting its Declaration of the Rights of Man, before it degenerated into the infamous “reign of terror” of which Paine himself became a target, and wound up in prison until the then Ambassador James Monroe rescued him in 1794. Paine remained in France until 1802, when Thomas Jefferson invited him back to the United States. In the end American religious politics rejected his secular ideals, and Napoleon co-opted both the Church and the French Revolution to recreate an imperial temple-state that Paine had so bitterly opposed.

As a bonus, Granados poses a leading ethical-moral question at the end of each chapter, and invites the reader to access a website for posting responses. Any compassionate person who reads this book is likely to identify with its heroes and heroines and to somehow feel better about being a humanist—as well as having learned that humanism indeed has a compelling and inspirational history of its own, from ancient times to the present. Thanks to Granados we can all take pride in this extraordinary humanist heritage.