Colobus Conundrum

No matter how deep I am in the forest, the sounds of humanity seep through, reminding me that the Abuko Nature Reserve in The Gambia is at once a mosaic of habitats, a home for the endangered red colobus monkeys and various other species, and simply a tiny forest—smaller than Central Park in New York or Hyde Park or Hampstead Heath in London.

Dogs bark, cocks crow, donkeys bray, grain is pounded, axes are wielded: the sounds of the bordering villages come wafting across the savannah and deep into the riverine forest. On Sunday mornings I hear church bells ring and choirs sing. On Fridays at two o’clock in the afternoon I hear Muslim prayers recited over a loudspeaker. And on most holidays and weekend afternoons I hear music from radios and cassettes, and drums, whistles, and cheering when football or wrestling matches are held.

This is merely a forest blip in a small, finger-shaped country on the coast of West Africa. It’s also where I straddle two worlds—one foot in the human world, one foot in the monkey world. To be honest, most of the time these two worlds collide and confuse me.

People here, especially women, rarely enter the forest. I was, and still am, considered slightly mad for spending so much time in the “not safe bush” on my own. “Don’t you get scared in Abuko?” I’m frequently asked. “Shouldn’t someone come with you?” “Do you have special powers to protect you from the snakes?” They also tell me the forest is full of djinns, invisible spirits mentioned in the Koran that are said to inhabit the earth and appear as humans or animals to intercede in human affairs. “Do you have special jujus to protect you from the djinns?” a local woodcarver asks me.

According to one of the forest rangers, toubabs (whites) and African people are different: “Our skin and our blood is stronger,” he says. “And we are better at smelling and hearing and feeling, and that is why we know there are djinns and you don’t know. Does the hair on your head sometimes stand up and does your heart go thump because you meet something different than you?” he asks. When I tell him that the only time my hair stands up or my heart thumps is when I’m surprised by a snake, the ranger puts his fingers on my eyelids and says, “I don’t know how you can say you know Abuko and the monkeys and the pythons if you don’t know how to use these. It is not what you look at; it is what you see that is important. You do not understand that what you think you see is sometimes not what’s there.”

But in spite of all the warnings I feel safe in the forest. It’s my haven, my shelter. For me there is nothing to fear here, no large predators (they were killed off decades ago). The only possible animal danger comes from snakes, which I’m cautious of; sometimes I even stomp and hum out loud to warn any pythons, cobras, mambas, or puff adders of my approach. Yet, I actually relish my snake sightings. In fact, I never feel as though I’ve had a completely satisfying day unless it includes a slightly scary serpentine encounter. Potentially, the most frightening thing to me in the forest is that nothing will happen. I have an almost pathological terror of being bored. So far that hasn’t happened.

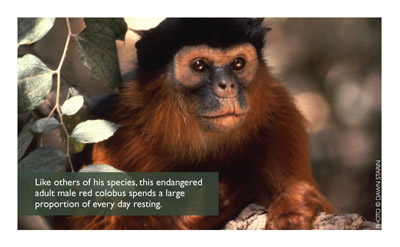

Sitting under a tallo tree swatting away the mosquitoes and the tsetse flies and squashing ticks between my thumbnails, a red colobus soap opera unfolds in 3-D Technicolor above my head. This is sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll colobus style.

The members of two opposing troops—mostly the males—chase each other back and forth through the branches and down to the ground. While the subadults and adults call, threaten, and chase each other, squealing infant males follow closely behind, forming a cheerleading squad. The infant males follow so closely behind that the older males often trip over them during the chase. A young oestrus (sexually receptive) female is attempting to switch troops, and both sides are vying for her uterus, the future home of the next generation. If a high percentage of females transfer on the same day, things can get a bit chaotic, but in the long run transfers have little effect on troop size and composition, since females who leave are gradually replaced by females from other troops. However, this does mean that the genetic composition of the troop changes continually.

The members of two opposing troops—mostly the males—chase each other back and forth through the branches and down to the ground. While the subadults and adults call, threaten, and chase each other, squealing infant males follow closely behind, forming a cheerleading squad. The infant males follow so closely behind that the older males often trip over them during the chase. A young oestrus (sexually receptive) female is attempting to switch troops, and both sides are vying for her uterus, the future home of the next generation. If a high percentage of females transfer on the same day, things can get a bit chaotic, but in the long run transfers have little effect on troop size and composition, since females who leave are gradually replaced by females from other troops. However, this does mean that the genetic composition of the troop changes continually.

When different red colobus troops engage in hostilities, the winning troop doesn’t permanently take over the loser’s territory: the winners simply move in for a while—maybe only an hour, maybe a day—use some of the resources, then leap off. The winners don’t capture mates. Young females aren’t kidnapped or dragged off kicking and screaming. Neither are they evicted from their birth troop. They simply move between troops at will.

Then another day dawns and another encounter ensues. Winners become losers and vice-versa. This small-scale hostility appears to work well. Resources are occasionally shared and potential breeding females are swapped. There is definitely competition, but the combatants don’t wage war. There is no pillage, no hoarding of resources. There is no rape. Instead, alliances are created and dissolved, friends are made and lost, altruism is promoted, selfishness is encouraged, wealth is redistributed, rivals are vanquished, self-esteem is lost and self-esteem is gained: a typical inter-troop encounter is similar to many human encounters. Think, for example, of a not-very-friendly, not-very-bloody football game between two rivals, whose fans wave flags, chant obscenities, and hope to win the cup—or, in this case, the resources. All of our so-called virtues and our so-called evils, our strengths and weaknesses, our warts and foibles and joys and sorrows—many of the very key factors behind humankind’s evolutionary success—are also part of what makes a colobus a colobus.

People sometimes wonder what it must be like to be someone else. I spend much of my time wondering what it must be like to be a monkey, to think like a monkey. And much of this wondering leads to total frustration.

People sometimes wonder what it must be like to be someone else. I spend much of my time wondering what it must be like to be a monkey, to think like a monkey. And much of this wondering leads to total frustration.

Sometimes when I watch the colobus I’m swamped with intellectual dread and confusion. I know that we share a very distant family history, and I know that what makes us human is not uniquely human. Murder, compassion, and morality stem from our common past. But the colobus’ behavior, not to mention their raison d’etre, is often beyond me. I have no idea what they think or feel. I’ve spent years associating with these thumbless, pot-bellied, clumsy acrobats, yet the simplest questions often panic me. Why do they sometimes walk right up to me—even bump into me, and other times I can’t get within 150 feet of them? Why don’t they have opposable thumbs? All other monkeys do. Why do the young ones close their eyes whenever they play on the ground? Isn’t that dangerous? Why is it that one old female always lies in the same position on the same branch in a certain mampato tree, and none of the others seem to have favorite branches? Why do the males engage in tug-of-war stick fights, and the females don’t?

These questions may seem insignificant, but they haunt my days and sometimes even my dreams, because I believe the full picture of who these animals are can only be understood by comprehending the trivia and minutia of their daily lives. I think it is the layering, the addition and subtraction of the commonplace, the so-called unimportant and inconsequential details, the behavioral flotsam and jetsam that constitute the big picture and can provide answers. Quite simply, it seems to me that what is usually unconsidered is deeply considerable.

There is still so much I don’t understand. As my friend the forest ranger says, I have to learn to see. Yet I wonder, if I found the answers, would I be satisfied? Would I know what to do with the knowledge? Would I know where to place such “silly little facts” in the grand scheme of things?

Entering Abuko one morning I find a five-inch-wide trail that resembles a bald tire tread winding along a sandy path. It can only be a python imprint. Why can’t the colobus and the green monkeys recognize that this is obviously a clean, fresh python track, and that there could be a problem if they don’t move away? They pay no attention to it. They don’t seem to have made the connection that this track was made by a python. Yet I have watched them watching pythons make tracks. To me it’s so obvious: I see the track, I know a python might be nearby. I am alert. Laughing with eyes shut, the young colobus roll around on the ground next to and over the track, and the adults sit on it, eating fallen fruit. The greens chase each other back and forth over the track.

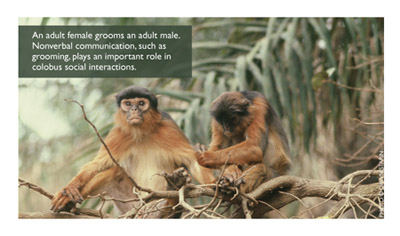

Whenever I observe a situation like this, I’m totally mystified. It’s hard to accept that I’ll never know for certain what goes on—or doesn’t go on—in the mind of a monkey. It’s hard to accept that there’s such a huge gulf between us, and that I could never truly develop an ability to enter into the thoughts and feelings of another species. As a human being, I can easily take a visual cue (a fresh python track), add it to an assumption (the python is probably nearby), and react accordingly (I should be careful). Humans look for patterns, causes, and relationships all the time. Do these monkeys? I don’t think they do in an obvious, regular way that I can comprehend. And so I come to the conclusion that they are so very different from us: just a bunch of monkeys. Then I see two colobus hugging and kissing, reassuring each other, using gestures humans use every day, displaying emotions we display everyday, and I decide that we do in fact share a lot with our very, very distant cousins.

What I experience is the simultaneously problematic and joyful reality of studying primates. It’s a non-stop to-ing and fro-ing, full of “are-they/aren’t-they like us?” dilemmas and “will I/won’t I ever understand them?” quandaries that occur on a daily basis. I am constantly looking for similarities, and when I’m hit head-on with so many extreme differences, it can turn my sense of self and others upside down.

Is it this very desire to know what others—familiar and foreign—think and feel, and to then relate this to our own feelings that partially makes us human? Is it the lack of this desire that partially makes monkeys just monkeys? And, is the very desire to know what others think and feel the very basis for human ethics, toward each other and toward our animal cousins?

I’m pretty sure biologists who work with worms and slugs and fruit flies don’t suffer this constant onslaught of schizophrenic confusion. I imagine their fieldwork is probably much less personal, more subdued, probably much more sane.

A green monkey with no left hand runs across the leaf litter. A colobus with a missing right hand sits in a mango tree. Elsewhere, two females and a male pin an alien male colobus down to the ground and kill him. They bite his legs, rip off his left testicle, leaving the right hanging by a thread, expose bones in his thighs, and rip major tendons and muscles. Their anger and fury appears infinite. An adult female colobus mother, clutching her dead infant with one arm, leaps from one palm tree to another. Three young colobus play on the ground, laughing and tugging and pulling at each other and rolling fist-sized pieces of termite mound along the forest floor.

Are these animals oblivious to the speckled light and the fallen logs in the shape of crocodiles and the lianas climbing up, falling down, lying sideways? They live in the middle of an oasis, a veritable feast for all the senses—a world even Henri Rousseau could not have imagined. Do they see the amazing beauty that surrounds them? What type of consciousness do they possess? Do they have “good” thoughts? Do they have “bad” thoughts? Are their usual thoughts linear or are they more often random? Do they revel in the world? Do they enjoy themselves in this very brief time they have in this extraordinary forest? Do they even have a concept of joy or reveling? Like humans, do they sit back and think of missed opportunities, paths not taken, alternative versions of their lives and themselves? Do they ever silently congratulate themselves? Do they have delusions and irrational beliefs?

These are the questions that really bother me, the questions I think about when I sit on the forest floor. What do the colobus and greens think about when they sit on their forest perches? Oh sure, I know their individual personalities and what they eat and who they like and who they want to chase away, and I am positive that they can feel fear and rage and lust, and probably even colobus-style love: but I have no idea what they think, or how they truly feel. Does a monkey resent the fact that it’s lost a limb? Does it replay the incident over and over again in its head? Do monkeys experience the pain, pressure, and itching of phantom limb syndrome?

What were the colobus killers thinking in their murderous frenzy? Were they even “thinking” during this whirlwind of extreme passion?

Does the colobus mother know that her dead infant will soon be so laden down with maggots that she will no longer be able to carry it around with her? Does she despise her infant’s killer? Does she want revenge? Is she in mourning?

I believe the mothers do feel a loss when their infant dies, but I don’t know whether they feel this loss until the end of their days. I’ve witnessed their screams when they come across a dead colobus in the forest. However, this doesn’t mean they understand death; these screams could simply signify “something isn’t right here.” Humans understand death, of course, albeit with variations on what happens afterward. I know I didn’t exist at one stage. I know I exist now, and I know that someday I will no longer exist. The idea of being nothing, then something, then nothing is probably—no almost certainly—beyond the colobus monkeys. Is this one of the major differences between them and me?

Conversely, when the young ones are playing and laughing, do they feel good? If so, what do the older ones do to feel like this once they’ve outgrown the play and laughter period? In humans, laughter releases endorphins—the natural feel-happy drug. And shared laughter creates bonds among people— it floods the brain with endorphins and makes us feel positively disposed towards the other person or group. Laughter can be contagious and uncontrollable. It helps dispel boredom. It brings on a rush of energy and joy. Is this true for the colobus?

There are always more questions than answers. Although this is frustrating, it’s probably the way it should be for all of us. I imagine that inquiries are the peaks of mental mountains, and that observing the world around us, asking questions, and seeking solutions is what drove our evolution.

As an anthropologist doing fieldwork, I’m alert to the dangers of the over-interpretation of the unobservable thoughts swarming around in monkey minds. I’ve often been warned about the pitfalls of anthropomorphism. However, as a field-working anthropologist, I have no problem accepting the possibility that there are a vast number of intricate mental gymnastics taking place inside the brains of these clumsy acrobats feasting and fighting and fooling around above my head. As an anthropologist and an evolutionist, I see us all intricately bound together, links in a chain, chapters in an ongoing story. I want to know who we humans are, where we came from, and where we might be going. I want to know what other species can tell us about our behavior. More importantly, as a fieldworker and a conservationist, I want to know what can be done to save these endangered animals and their forest from disappearing in this part of the world.

My questions persist, even when the lights are out at night and I’m falling asleep and trying to understand what it all means: sprawled out along thick mampato branches or curled around each other high up in the forest—are the colobus monkeys dreaming?