Beyond the Box

The day after Hurricane Sandy flooded the lowlands of New York City, a flurry of media inquiries flooded the Occupy Wall Street PR team’s inbox. Days before any aid organizations arrived, hundreds of Occupy Wall Street (OWS) activists had started coordinating teams of thousands of volunteers, climbing the stairs in dark housing projects, and checking in on needs for water, food, and medical care. OWS, also known simply as Occupy, was on the ground everywhere, simultaneously leaping into action from Red Hook, Brooklyn, to far-flung reaches of the Rockaways in Queens.

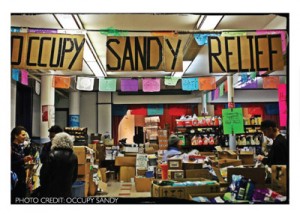

While immense institutions like the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) checked box after box, thousands of volunteers coordinated by “Occupy Sandy” lifted box after box into vans for shipment to the hardest hit neighborhoods in the region. Hour by hour, drivers stuffed their cars from floor to ceiling with flashlights, coats, and slippery tins of hot food, and headed to dozens of relief sites in the remotest parts of the Rockaways, Coney Island, and Staten Island. Across New York City, cooks crafted 20,000 meals daily, and Occupy Sandy and its NGO (non-governmental organization) partners made sure the food and supplies got to those who needed them most.

While immense institutions like the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) checked box after box, thousands of volunteers coordinated by “Occupy Sandy” lifted box after box into vans for shipment to the hardest hit neighborhoods in the region. Hour by hour, drivers stuffed their cars from floor to ceiling with flashlights, coats, and slippery tins of hot food, and headed to dozens of relief sites in the remotest parts of the Rockaways, Coney Island, and Staten Island. Across New York City, cooks crafted 20,000 meals daily, and Occupy Sandy and its NGO (non-governmental organization) partners made sure the food and supplies got to those who needed them most.

Our phones rang off the hook day and night. This time, rather than asking, “What are your demands? Who are your leaders? How are you organized?” now the press wanted to know, “Has Occupy re-branded itself as a relief organization?”

No, Occupy Wall Street has definitely not transformed itself into a relief organization, but it may be that it’s coming into its own as a kind of metaphorical relief movement. Zuccotti Park in lower Manhattan, site of the original OWS protests in 2011, was a disaster zone, an expressive space of refuge from the economic meltdown. There, OWS identified the root problem: economic injustice due to Wall Street greed, leading to a host of other grievances. The solution-oriented half of its message got lost. Occupy called for a sense of collective responsibility located somewhere on the spectrum between self-interest and self-sacrifice, otherwise known as mutual aid. It argued that our public bodies were so shattered, they could no longer be relied upon to respond to the needs of the hardest hit. Rather than waiting for reform, it was on every one of us to defend the common good. Daily mutual aid experiments at Liberty Square, as Zuccotti Park came to be known during the 2011 protests, prepped OWS well for disaster relief.

Working Together?

We all know that in the first seventy-two cold, dark, and dripping hours of a severe weather crisis, the most vulnerable—the elderly, the ill, those struggling with their mental health—can die. Yet it was only on day three that FEMA jackets started to appear. Red Cross trucks were hardly seen in most neighborhoods a week later. And while a few politicians walked around calmly promoting themselves, the New York City Housing Authority had no answers for the residents of its unheated and unlit projects, and refused to talk to the media.

What exactly does it mean that in all of these places, for days and days, Occupy Sandy together with its NGO partners constituted the only citywide relief effort on the scene? Only federal institutions like FEMA can offer homeowners financial support as they rebuild their homes. Only mega-NGOs like the Red Cross can truck in mini-hospitals to serve large numbers of injured people. Only the mayor’s office, housing authority, and utility companies can turn the lights back on.

What exactly does it mean that in all of these places, for days and days, Occupy Sandy together with its NGO partners constituted the only citywide relief effort on the scene? Only federal institutions like FEMA can offer homeowners financial support as they rebuild their homes. Only mega-NGOs like the Red Cross can truck in mini-hospitals to serve large numbers of injured people. Only the mayor’s office, housing authority, and utility companies can turn the lights back on.

But maybe getting things done in the first days of a collective crisis isn’t about expertise. More than anything, it’s about claiming agency, connecting with front-line communities without a moment’s hesitation, and thinking to ask them what they need—rather than imposing the cookie-cutter, assembly-line approach that often dehumanizes disaster victims. Informal, self-organized networks like that of Occupy leave space for compassionate engagement with traumatized communities—and individual attention can make a difference in life-and-death situations.

Moreover, as an unaffiliated, porous, distributed leadership network, Occupy Sandy is able to engage in mutual aid across communities. Repeatedly, NGO partners on the ground must reiterate their duty to the community they serve, and their inability to direct their energies towards other communities. Occupy Wall Street isn’t bound by these constraints, and can redistribute resources from one place to another according to shifting needs.

This is not about ideological purity. This is about different approaches to making change. For decades, strict hierarchical organizing models have failed to achieve systemic change on the scale we need. Yet we know that this movement alone will not make change either. It’s not an either-or proposition; especially when disaster strikes, there’s a clear need for “all of the above.”

At Liberty to Lead

So how exactly did Occupy’s mutual aid efforts in one park evolve into the distribution of 20,000 meals a day in the wake of a hurricane? How did Occupy Wall Street, after being pronounced dead a thousand times over, produce Occupy Sandy? From a host of medical and legal professionals with deep ties to citywide and national networks to seasoned kitchen crews accustomed to serving thousands daily to rock-solid web platforms built by devoted developers, a range of Occupy-created tools were in place and ready for application. But where did all these tools come from?

If Occupy Wall Street is anything, it’s a call for people to act on their own behalf. There is something profoundly liberating about doing what you want to do, about that which you care most; a spirit catches hold that instantly motivates you to turn on a dime. This distinguishes movement energy from that of the NGO, which must usually steer its constituency to get behind a particular long-term campaign for which it fundraises, and upon which its survival and identity relies. And whereas NGOs often find that volunteers take up more energy than they give, Occupy sparks volunteer-driven action. In the space of Liberty Square, the recommendation to “follow your passion” was no cliché, it was a guarantee that new experiments would unfold, and new leaders incubate.

Case in Point: Some of the New Leaders of Occupy Sandy

Four days after Hurricane Sandy slammed New York City, a distressed woman from the Red Hook neighborhood of Brooklyn slouched into an ad hoc Occupy Sandy “doctor’s office,” spine hunched, eyes downcast. One of two doctors on site sat on the edge of a table and asked what she needed.

“I just need to talk to somebody.” Tears splashed off her chin and soaked into the front of her shirt. “It’s so dark… and I’m afraid to go down all those stairs in the dark.” Nodding compassionately, the doctor asked a few gentle questions until he got down to the bottom of the matter. The patient was out of her medication, had spiraled during her isolation, and lost her ability to refill her prescription. She hadn’t “seemed” mentally ill; everyone in Red Hook was feeling the way she was. But because this doctor took time to listen, it’s possible he saved her life.

This doctor had arrived just two days earlier ready to sort baby diapers and match winter gloves like any other volunteer, when the too-obvious dawned on him: his skills as a doctor were in need. If he had approached the Red Cross offering to help, he wouldn’t have been able to get to work on day one. He had no prior involvement with the Occupy movement, and it’s likely he won’t identify with OWS in the weeks to come. But because of Occupy’s participatory leadership principles and practices, he was able to self-organize fifteen medics, all of whom accomplished amazing things.

In another case a week after the hurricane, a volunteer stopped at a new distribution center run very differently from an Occupy Sandy site down the street. With rumors of hoarding about, the lines at this new center were strictly controlled to assure equitable distribution of resources. The volunteer needed to coordinate with those running the show inside, so she jumped to the front of the line. While she was allowed in without hesitation, two women next to her—one of them visually impaired, the other having difficulty standing—were chided for jumping the line. This approach was clearly due to the enforced line between service provider and recipient. But this is exactly the line Occupy Sandy seeks to do away with. Turned away at the ultra-efficient site, the two women with special needs headed down to the looser Occupy Sandy site, where they got what they needed. One even ended up volunteering the rest of the week.

Most people involved with OWS retain a powerful conviction that cooperative instincts are as powerful as tendencies to hoard or compete for resources. So what’s the best way to assure equitable distribution: Tight policing of underresourced people? Or fostering access through a commitment to inclusivity, especially when there’s enough to go around? And yet in one of the richest yet most stratified cities in the world, so many are excluded from access to resources.

Disaster Collectivism: Building Resilient Communities

Still, Occupy Wall Street isn’t about band-aid thinking; even mutual aid experiments liberated from the service-recipient mindset don’t cut it. Next steps include taking on the threat of “disaster capitalism” looming in the wake of demolitions along valuable beachfronts and confronting the forces behind rising sea levels. The movement’s target: Wall Street’s direct role in bankrolling climate chaos and its role in defunding and corrupting the very public institutions we will all need most as climate change-related disasters escalate. Occupy Wall Street has finally started to get the mutual aid message across, but must continue to project a systemic critique.

At Liberty Square, OWS met the deep need to howl the most repressed and silenced parts of ourselves, as individuals and as a country. Today, Occupy Sandy is meeting a visceral need to build strategic and tangible relationships with front-line communities based on mutual interest, which is a step towards mobilizing the kind of mass movement that can make change. Even if mutual aid can’t stop the source of climate change, it can definitely nurture resilient communities as they fight the results of rising sea levels. And ideally, Occupy Sandy can transform its new “relief web” into a network capable of reclaiming common resources and public goods—before disaster strikes again.