Getting Humanism Right-Side Up A Reality-Based “Mattering Map” and Alternative Humanist Manifesto

WHAT IS HUMANISM? Some say it’s a godless worldview, a philosophy free of supernaturalism. But humanism is both more and less than that. More, because it is about affirming what we do believe, not just denying what we don’t. Less, because it is probably unwise to deny the designation “humanist” to those who share our core values but are unable, so far, to free themselves of god-belief. Guarding the gates to a grudging tribalism is no way to spread humanism; far better to welcome humanistic theists into our ranks, engage them in friendly dialogue, and allow honest inquiry to work its magic. They will overcome their religious attachments—or not—in their own time. Meanwhile, the community of people dedicated to honest inquiry will grow.

I am an atheist, but I choose to self-identify as humanist. Why would I define myself reactively, that is, in opposition to another’s viewpoint, when I can instead choose a proactive identity? Making atheism prerequisite for humanism just makes us appear exclusionary, reactive, and oppositional. It also feeds the myth, propagated by our cultural opponents, that nonbelief is a presupposition of our worldview—an initial doctrinal requirement rather than a contingent outcome of fair-minded inquiry. So let us be clear and also brand-savvy: our atheism, where it exists, is secondary; it grows out of prior—and deeper—convictions.

When we attempt to articulate our deeper convictions, though, a funny thing happens: they proliferate without end. We believe in human rights; we trust reason, science, and freedom of inquiry; we affirm the importance of justice, compassion, and tolerance; we actively promote education, creative expression, and democratic self-actualization. And so on. We gather these fine sentiments, and in an attempt to define what we’re about, bundle them into “manifestos.” These compilations—long lists of lofty principles and noble affirmations—are worthwhile. No doubt they add something important to our culture. But let’s be candid: these manifestos are also unwieldy, incomplete, and, to many a modern ear, banal. Each is a stew of concepts with positive associations, a grab bag of humanistic sentiments. Worse, these manifestos fail to differentiate our lifestance from other worldviews that claim these values. (After all, what outlook doesn’t claim truth and compassion as its own?) Those who seek an incisive understanding of humanism, then, may be forgiven for wondering: What is it that ties these humanist affirmations together? Is there a central thread or underlying commitment? Does the philosophy have a foundation, a touchstone of some sort? What anchors humanism?

It’s a fair question. It merits an answer, one that doesn’t brand us as reactive or oppositional. My proposal is this: at bottom, humanism is a commitment to developing a shared and responsible understanding of what really matters, and living accordingly.

I’d like to show that this formulation is both apt and advantageous. First, though, let’s explore its meaning. The phrase “really matters” implies that, when it comes to mattering, it’s easy to be misled by appearances. In other words, we often care about things that don’t genuinely matter, and fail to care about things that, as it turns out, really do. We discover such misdirected sentiments all the time. For example, a father can come to realize that his obsessive pursuit of career advancement was a mistake—he should have spent more time with his children. A politician can examine the evidence for climate change and reverse her opposition to renewable energy subsidies. A minister can grapple honestly with the problem of evil and lose his faith. The point is that critical reflection can, and often does, compel rational people to revise their affections; no one but a radical skeptic doubts that this happens, or denies that inquiry can straighten out our priorities.

A humanist, then, is someone who understands that it’s easy to be mistaken about what matters. We “get” that even our most cherished convictions can be wrong, and seek understanding with minds as resolutely open as we can manage. We strive to get behind the appearances, and then, in light of what we learn, to update our mental “maps” of what matters. Of course, this makes our worldview a shifting target: an ever evolving work-in-progress.

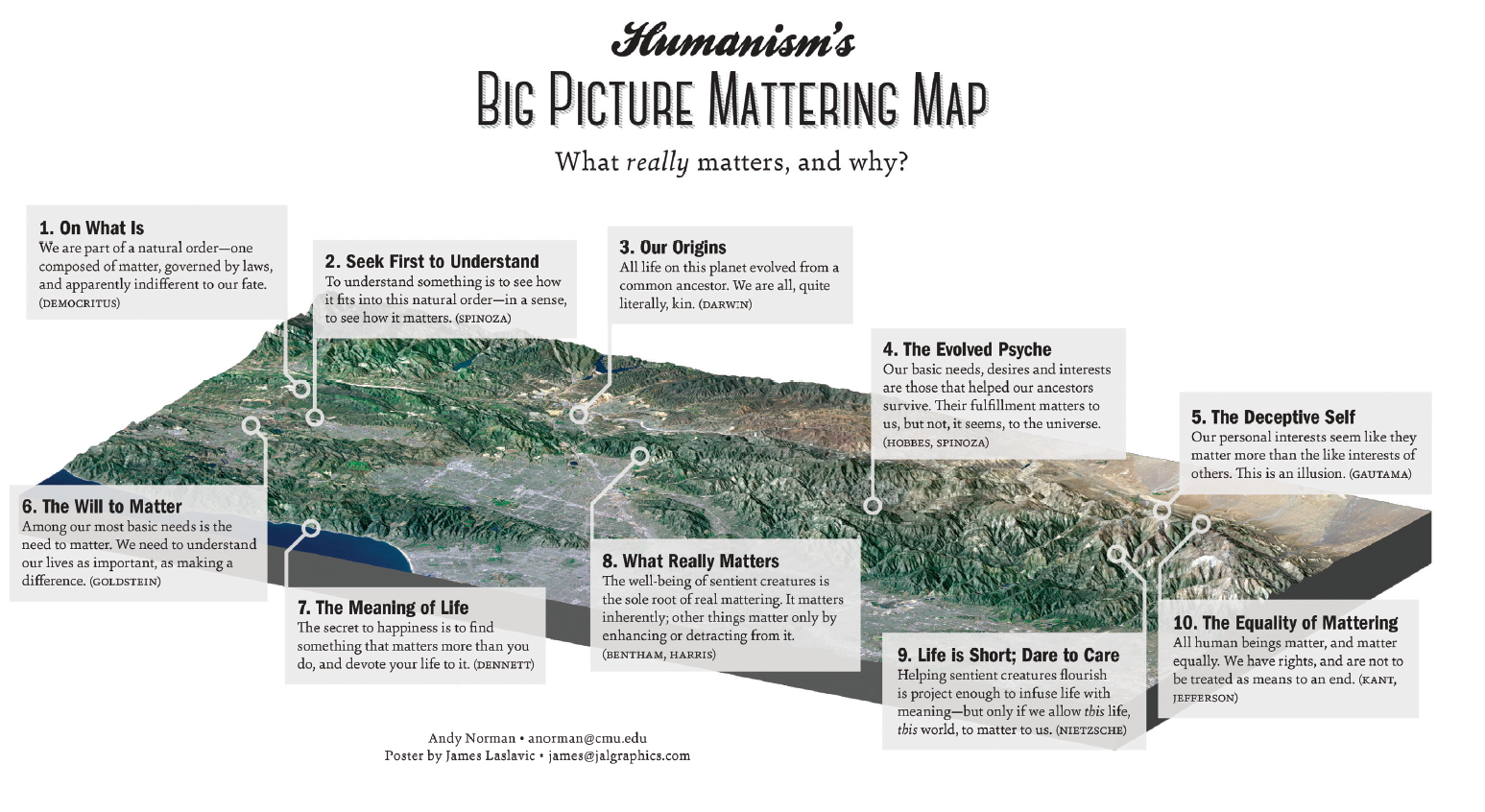

CLEARLY each of us harbors some understanding of what matters. Such understanding is invariably partial (in both senses: incomplete and biased). Imagine this understanding represented in a 3-D “topo” map, where the things that seem to matter a great deal occupy peaks and the things that seem to matter less occupy valleys. Such maps orient us in the world. We consult them, usually by attending to our practical/moral intuitions, and they provide immediate, valenced feedback: the kind of rapid assessment needed for real-time navigation. Of course, information about what matters to us is actually encoded across multiple platforms: our moral and practical intuitions, but also our genes and our brains, our dispositions and our sentiments, our habits and rituals, buildings and artifacts, stories and curricula, sacred texts and to-do lists. The distributed nature of the encoding, though, need not concern us here; because we act as if oriented by mattering maps, the metaphor is worth taking seriously. A mattering map, then, is just a virtual representation of what matters. (The concept originated with the philosopher Rebecca Goldstein; it has since become a useful tool for psychologists and behavioral economists.)

As a rule, humanists recognize that we have an obligation to continually refine and update our mattering maps. For this is the essence of moral growth. We understand that accurate mattering maps make more reliable guides to living well, and we take seriously the responsibilities of what we might call moral cartography. After all, what else besides an apt mattering map can guide us to a life that, on reflection, genuinely matters? Note though that the accuracy of a mattering map is not the only thing about it that counts: it matters also that it be shared and is relatively stable. Shared mattering maps have great power to resolve moral, political, and/or theological differences. They can orient us collectively and help us act in concert. Stable mattering maps offer the promise of sustainable meaning—a sense of purpose that is not “here today, gone tomorrow.” Few things are harder to face than the possibility that one has devoted a significant portion of one’s life to something that doesn’t really matter. Far easier to delude oneself, and cling tenaciously to the delusion.

Religious ideologies are best understood as crude, fanciful mattering maps—well intentioned but clumsy attempts to afford a stable sense of meaning and shared sense of purpose. People need to feel that they matter, and religions cater to this need. They do this by providing fellowship, belonging, and community—arguably elements of real mattering—but also by assuring their followers that they matter to God. (The central message of Rick Warren’s mega-successful book, The Purpose-Driven Life, is “You matter to God.”) Monotheisms have long peddled ideas that function in similar ways: God cares; we are God’s chosen people; you were made in God’s image; God sacrificed his only begotten son for you; you too can become an instrument of divine providence; you can matter by saving souls; and so forth.

The concept of mattering maps sheds a penetrating light on some of the most striking features of monotheistic religions. Consider the fact that religions induce modern, educated human beings to pretend to know things they can’t possibly know—that Jesus was born of a virgin, that he rose from the dead, that God created the universe in six days, that he rewards believers with everlasting life, and so on. How does Christianity get otherwise sophisticated and intellectually responsible people to engage in such pretense? Surely it is because the pretenses afford a shared sense of mattering—and with it, presumably, relief from existential anxiety.

But this only works for those capable of suspending disbelief. Thus, pretense-based mattering maps must take unusual steps to protect themselves against reality-based degradation. Religions, of course, are not the only ideologies with defense mechanisms—in fact, all ideologies have them—but religious ideation offers a stunning case in point. Consider the astonishing range of map-stabilization strategies that religions employ: they brainwash the young (“Raise children in the faith”); celebrate irrational obstinacy (“Faith is a virtue”); seduce believers with promises of salvation (“Live forever!”); and threaten doubters with eternal torment (a psychologically abusive and sometimes traumatizing form of mind-control). They discourage believers from engaging nonbelievers (“Beware of wolves in sheep’s clothing,” “Don’t listen to atheist devilry”); employ evasion and distraction (“God works in mysterious ways”); and even enjoin violence and intimidation (“Kill infidels!”, “Stone apostates!”). The felt need to protect religious mattering maps has spawned oppressive theocracies, bloody jihads, sadistic inquisitions, witch burnings, suicide bombings, fatwas, pogroms, and genocides. History teaches that people will do almost anything to protect their sense of mattering—especially if it is based on a fragile ideology. Consequently, ideologies develop playbooks full of scurrilous defense mechanisms.

On the interpretation I am offering, humanists have, for millennia, been quietly assembling and promoting a responsible, evidence-based mattering map—an alternative outlook that can serve all of us in our struggle to live meaningful lives. Humanism, in other words, proposes to provide a mattering map capable of aligning our intentions, not just with those of our fellow humans, but also with the facts. Humanity needs a shared and reality-based mattering map, otherwise our life projects will forever be at cross-purposes—with each other, with reality, or both. Trying to live a good life guided by a pretense-based mattering map is like trying to navigate New York City with a map of Tolkien’s Middle-earth.

To fully realize its promise, though, humanism must afford not just a guide to mattering, but the mattering itself. The humanist worldview is a great start, but our projects and communities must also afford real purpose. What makes humanism unique, of course, is that it proposes to do this without the delusions, moral disorientation, or skewed priorities that so frequently attend pretense-based mattering maps.

The accompanying “Big Picture Mattering Map” is my attempt to capture, in brief, what centuries of patient inquiry have taught us about genuine mattering. Each element represents a hard-won truth, one that sheds important light on what does and doesn’t matter. Like guardrails on the road to a life of real mattering, each principle blocks one or more seductive, pretense-based detours. (See if you can identify the most seductive detour blocked by each element: it’s both fun and instructive!)

At its best, humanism inoculates us against ideology, conferring a kind of immunity to the most seductive strains of pretend mattering. I am suggesting that it can also provide a relatively clear view of the mattering landscape—one that can actually orient us morally. It can help us live lives that truly matter.

I invite you to dwell at length on the map. Notice that the concept of mattering is like a thread that ties together humanism’s disparate elements. Consider the possibility that honest mattering is in fact our core commitment. See if this way of viewing things lends clarity and coherence to your outlook. And consider the value of being able to foreground what we’re for: being against religion is curmudgeonly, but being for honest mattering is noble and inspiring. Isn’t it time we supplemented our longstanding “No!” with a resounding “Yes!”? Let’s turn humanism right-side up.

The reframing should empower us to come out of our respective closets: to own our humanism with pride and purpose. It also repositions us culturally: Why languish in the niche market for rational philosophies (where no one is buying anyhow), when we can compete in the bustling mattering market (where demand is robust)? The recasting should open hearts and minds to our message, and make humanism a contender for real mindshare. Best of all, if we successfully reframe the culture war as a choice between honest and dishonest mattering, we can’t help but win in the end.

Take pride in your humanism. Share it with confidence. We stand for nothing less than a world in which pretend mattering has been rendered obsolete, not just by evidence and logic, but by forms of life that afford well-being, creative fulfillment, and honest-to-goodness mattering for all.