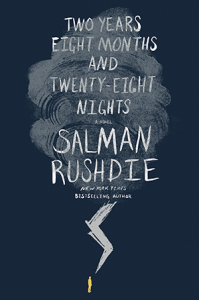

Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights

BOOK BY SALMAN RUSHDIE

RANDOM HOUSE, 2015

304 PP.;$28.00 (HARDCOVER), $13.99 (KINDLE)

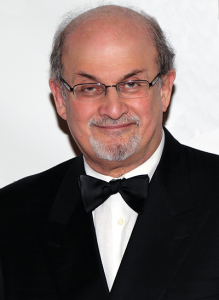

This past September the celebrated and controversial author Salman Rushdie published Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights—his first adult novel since Enchantress of Florence in 2008. Rushdie’s commented that he wondered what it would be like to write a fairy tale similar in style to his two children’s books but for adults. In fact, the novel reads very much like Haroun and the Sea of Stories and Luka and the Fire of Life, both written for his two sons when they turned ten. Although Rushdie claimed that it “might be the funniest” of his novels, it is actually his most overtly political fiction.

The story begins in the year 1195 with the exile of Ibn Rushd, based on the historical figure known to the West as Averroes—the philosopher credited with bringing the work of Aristotle to Europe and popularizing secular philosophy in the West. He is expelled from the Almohad court in Arab Spain because of his “liberal ideas” about nature and God. Unbeknownst to Ibn Rushd, a great princess of the jinn chooses him to explore the human experience of love. The jinnia bears him more than thirty children in a matter of years with the spectacular fecundity unique to the jinn, and the descendants of their union spread out across the world linked only by their curious lack of earlobes and their hidden jinn potential.

Eight hundred years later, the “slits” between the jinn world and the human world open up, enabling a dark sorcerer-jinn to wreak havoc on humanity in the service of Ibn Rushd’s enemy, Al-Ghazali (based on the historical theologian known for his views on God’s supremacy over the laws of nature). The jinnia urges Ibn Rushd to claim his descendants in order to fight the evil forces of the dark jinn and Al-Ghazali. With his approval, she proceeds to unlock the hidden jinn powers in their descendants who come to her aid in fighting the lower- and higher-order dark jinn throughout the world. Al-Ghazali seeks to frighten humanity because “only fear will move sinful man toward God.” Eventually the princess jinnia, along with a group of her most gifted descendants, defeats the dark jinn and saves humanity.

The story, which itself contains many stories within stories, is told by a future group of humans living one thousand years after the conflict. This futuristic human society is not only atheist, but also above superficial divisions like race and free of the disturbing violence that has plagued humankind for the majority of its history.

It is clear from the outset that Rushdie identifies with Ibn Rushd not only because he is his namesake, but also because they both share “the ideas that had led [their] books to be burned.” Indeed, one of the major unifying thematic devices in the story are the references to Scheherazade in the 1,001 Arabian Nights. Rushdie’s title is a nod to the text as is his layered story structure. Ibn Rushd, and by extension Rushdie, sees himself as a “sort of anti-Scheherazade […] her stories saved life, while his put his life in danger.”

Additionally, Rushdie sees Ibn Rushd as both free-spoken, like himself, and eerily prophetic about what is to come: “To be thin-skinned, far-sighted, and loose-tongued,” Rushdie writes, “is to feel too sharply, see too clearly, speak to freely. It is to be vulnerable to the world when the world believes itself invulnerable, to understand its mutability when it thinks itself immutable, to sense what’s coming before others senses it, to know that the barbarian future is tearing down the gates of the present while others cling to the decadent, hollow past.” In his memoir Joseph Anton, Rushdie suggests that he had similar powers of perception when he viewed his experience with the fatwa as the “first black bird” in a series of assaults on Western secular philosophy that would culminate in the terrorism of 9/11 and 7/7. Rushdie writes regretfully and thankfully that Ibn Rushd, who was ultimately asked to return to court shortly before his death, would never live to see both the impact his work had on Western secularism and the triumph of Al-Ghazali’s theology over his philosophy within the Arab world.

This is perhaps Rushdie’s most overtly pro-atheist work. His narrators are part of a futuristic human society and describe faith in religion as an illusion, a fantasy that is responsible for “repression, horror, tyranny, and even barbarism.” He constructs an absolute dichotomy between science, reason, and logic on one side and religion, unreason, and faith on the other.

This is perhaps Rushdie’s most overtly pro-atheist work. His narrators are part of a futuristic human society and describe faith in religion as an illusion, a fantasy that is responsible for “repression, horror, tyranny, and even barbarism.” He constructs an absolute dichotomy between science, reason, and logic on one side and religion, unreason, and faith on the other.

Religion is consistently aligned with violence throughout the story (“A crowd of the faithful, for whom hostility seemed to be the necessary sidekick of fidelity”); characterized as superstition (“The battle between reason and superstition may be seen as mankind’s long adolescence, and the triumph of reason will be its coming of age”); and completely irreconcilable to Western, liberal philosophy, which is based on “ideas that have no need for belief” (emphasis mine). Science, reason, and logic, however, are aligned with knowledge, civility, and restraint. Although he ostensibly critiques all religions, including references to extreme Hinduism and American evangelistic Christianity, his whole narrative war is with a particular “Arab” version of Islam. The base of operations for the dark jinn is a thinly disguised allusion to Afghanistan.

Because Rushdie is telling the story from the point of view of future humans, he has a number of reflections on the complexity of historiography and its relationship to truth and untruth. His narrators acknowledge that the story, having taken place so far in the past, might be more myth than truth, and they unapologetically tell the story anyway: “if made-up stories have been introduced into the record, it’s too late to do anything about it.” At the same time, he writes at length about the consequences of equivocation or relativity when it comes to truth, and “that [it] is too important an idea to give up to the relativity merchants. Truth exists.” This is one of the many ambiguities that riddle the novel and its conclusions about reason, truth, and humanity.

As the story draws to a conclusion, the narrators note that after the slits between the worlds closed for good (and an age of reason replaced humanity’s fascination with religion), humans stop dreaming: “This is the price we pay for peace, prosperity, understanding, wisdom, goodness, and truth: that the wildness in us, which sleep unleashed, has been tamed, and the darkness in us, which drove the theatre of the night, is soothed,” and yet they conclude their story by expressing a “perverse” desire for nightmares.

Ultimately Rushdie concludes that humans are “storytelling animals” in whose nature the desire for imagination and fantasy is embedded. In this way he ends as he begins, concluding with a quote from George Szirtes that draws a distinction between fairy tales and religion and suggests that while humanity needs one, it does not need the other: “One is not a ‘believer’ in fairy tales. There is no theology, no body of dogma, no ritual, no institution, no expectation for a form of behavior. They are about the unexpectedness and mutability of the world.”