Call in the Robocops With Democracy at Risk, Can We Quell Internet Bots & Trolls?

Illustration © Frenta | Dreamstime

Illustration © Frenta | Dreamstime RELAX. An army of content reviewers some 10,000 strong is busy weeding out malicious posts and fake news from your favorite social media. Soon, it will double in size.

Feel better? You shouldn’t. The social media platforms nearly all of us use teem with “bots,” artificial intelligence modules that impersonate human beings and tirelessly fill our heads with propaganda. Facebook admits its pages may harbor as many as 270 million fake accounts. That’s more than all the people in Brazil. Or Indonesia. Or Pakistan. It’s more than the adult population of the United States.

Twitter, too, is rife with fakes. The short-message platform has proven ideal for pummeling targets with crude, virulent takedowns and disinformation.

“We’re only beginning to grapple with this,” says the University of California-Berkeley’s Ming Hsu, who leads a team working on the challenge. “There’s a whole world out there that we don’t understand well.” We’ll return to Hsu later for some ideas on how to respond.

Trolls (online purveyors of hateful content) can vastly fortify their bile using bots. The comedian Leslie Jones closed her Twitter account in July 2016 after being barraged by vile tweets. The messages, which compared her to an ape, falsely imputed homophobic quotes to her, and made sexual threats, appeared to come from aggrieved fans of the film Ghostbusters who objected to a remake with a female cast that included Jones.

The dust-up foreshadowed a Twitter tornado during last fall’s presidential election. According to the cybersecurity firm FireEye, tens of thousands of Russian Twitter bots worked tirelessly to push hashtags likes #WarAgainstDemocrats and #DownHillary into Twitter’s trending zone. But there’s worse. Much worse.

Recent Congressional hearings revealed that Russian operatives were able to foment street clashes in Texas by using fake activist sites to steer American Muslims and rightwing anti-Muslims to the same spot at the same time for—you got it—fake rallies.

Social media offer cheap and easy ways to stir mischief. Investigations led by ProPublica have shown that automated advertising tools on Facebook, Twitter, and Google can be used to target and inflame bigots, or to target or exclude whole races and ethnic groups. Starting with Facebook, ProPublica tested whether the social media giant would let them target “Jew haters.” Their ad buy was approved in fifteen minutes. A similar test at Google found the search system offered up additional targeting suggestions such as “black people ruin neighborhoods” or “Jewish parasites.” The companies all proclaim that such targeting violates their standards, but the artificial intelligence (AI) they deploy remains mostly blind to invidious content.

KREMLIN COUP?

Among the ads that have since been traced back to Russian origins were many that used vicious stereotypes and scare tactics: they mocked gays, smeared immigrants, invoked the devil, and portrayed Hillary Clinton as in league with Muslim terrorists.

“The social media ads, posts and pages that have been revealed to come from Russian agencies or operatives in 2016 used explicitly anti-Black, anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant stereotypes to undermine the American electoral system, suppress voter turnout and fan the flames of racist hatred and violence,” Malkia Cyril, executive director of the Center for Media Justice, said in a statement to The Nation.

They achieved a staggering reach. From fake papal endorsements of Donald Trump to sinister claims about Clinton, bots pumped out one-fifth of all tweets during the month leading up to the election. That’s according to Emilio Ferrara, an assistant professor of machine intelligence at the University of Southern California. Ordinary people were unable to distinguish them from authentic tweets, he said.

Considerable effort went into derailing Clinton voters. The Blacktivist page riveted African Americans during last year’s campaign. The site’s most shared posts were graphic, emotional, and wholly plausible claims about police killings of unarmed blacks. Its reach of 104 million shares exceeded that of Black Lives Matter. But Facebook now says that Blacktivist was one of hundreds of Russian-operated disinformation sites. The intent in this case was evidently to deter African Americans from voting.

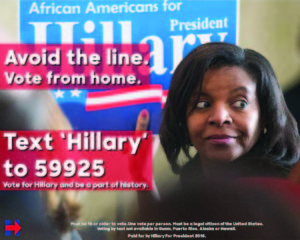

In the final weeks of the election, a meme falsely offering voting by text went viral. (Simulated meme created by the author.)

In the final weeks of the election a cunning meme raced through Facebook, Twitter, and other social media. It suggested that “African Americans for President Hillary” could save time by casting their votes from home via text.

The meme went viral. No one knows how many people it tricked into wasting their votes. Media analyst Kathleen Hall Jamieson of the University of Pennsylvania thinks it may have been decisive. “It’s hard to know what effect Russian ads, posts, and tweets had on voters in the states that narrowly decided the 2016 election,” she writes. “But the wide distribution of strategically aligned messages increases the likelihood that Russian efforts changed the outcome of the 2016 election.”

Russian interference via Twitter has also been detected in France and Germany’s recent elections. That’s concerning enough, but the political effects of bots aren’t limited to elections. A research group led by Ferrara found that upwards of 15 percent of Twitter accounts are bots. That implies as many as 50 million fake accounts. A remarkably thick slice of them are followers of Donald J. Trump.

FAKE MUSE

As president, Trump has made unprecedented use of his personal and official Twitter accounts. Doubtless, that has attracted many new followers, both supporters and critics. Curiously, though, the fastest growth in his @realdonaldtrump account has been among nonhuman fans. According to TwitterAudit, nearly half of Trump’s followers are bots.

Having nearly 20 million fake followers may be an ego boost for the president, but it can distort both the public’s and the White House’s perceptions of how his often provocative messages are received.

In August Trump thanked and retweeted a supportive message from a “Nicole Mincey,” who appeared to be an attractive young African-American woman so loyal to the president that she chose the handle @ProTrump45. Skeptical Twitter users soon found reasons to believe she was a bot: her profile image appeared to be a stock photo, her biographical details were nil, and her messages were mindlessly pro-Trump. Shortly afterwards, Twitter shut down the account.

Automated flattery carries a price. Trump’s heavy reliance on Twitter means that he may be vulnerable to policy manipulation through the medium. One human troll amplified by nearly twenty million bots could give the president a false sense that some idea he has floated—such as war with North Korea—has grassroots support.

The public policy implications haven’t gone unnoticed. In November the Senate Intelligence Committee showed rare bipartisan flint in sharply questioning Facebook, Google, and Twitter. However, the companies, accustomed to favorable treatment on Capitol Hill, sent their lawyers rather than top executives to the hearings. In testimony, Facebook general counsel Colin Stretch admitted that Russian operatives were able to mount a “pernicious” campaign that reached more than half the electorate. He also admitted that Facebook has yet to identify the full extent of Russian encroachment on its platform.

“These people were not amateurs,” Stretch said. “It underscores the threat we’re facing and why we’re so focused on it going forward.”

But are they? The tech giants have little incentive to root out fake accounts. In the same week as the hearings, Facebook announced record profits and a stunning 2.07 billion accounts—implying that it embraces more than a quarter of humanity. Walking that back by deducting, say, a quarter of a billion fake accounts would be costly and humiliating.

It’s not a dilemma Facebook faces alone. Other tech giants’ income likewise depends on user numbers. Twitter is especially vulnerable to a stock-price hammering if their account base drops, says Scott Tranter, a technology consultant cited by Bloomberg Businessweek. Civic outrage alone won’t overcome investor ultimatums. Things could change, however, if public pressure combines with a customer rebellion.

ADVERTISER ANGST

Many companies loathe having their brands posted next to viciously racist, sexist, or homophobic posts. Online advertisers have another problem: they’re wasting money on ads seen by bots, faraway trolls, and internet ghosts. The scale of the problem became clear when an Australian investigation revealed that Facebook’s reach to millennials in that country exceeded the actual population of twenty-somethings by more than 30 percent. An overreach of some twenty-five million nonexistent millennials appears in Facebook’s US numbers.

Until recently, Facebook has often responded to such complaints indifferently, and sometimes weirdly. Pakistani trader Ammar Aamir, for example, wrote to the Facebook business forum: “Whenever I post an ad, the majority audiences that are engaged by Facebook are fake accounts. Please remove the fake accounts from your database. I am extremely disappointed. These cheap tactics do not suit Facebook.”

The sole response came from Denis Piszczek, allegedly an online entrepreneur based in Germany. A review of his account shows nothing in his sparse postings that matches up with the breezy, condescending language of the response. Indeed there’s no evidence that Piszczek is an English speaker. Or a speaker at all. He’s not typed one original word in the last five years of his Facebook timeline. Yet, in fielding Aamir’s complaint, Piszczek turned positively loquacious: “Hi Ammar, This usually happens organically, when someone inside of your target demographic shares your ad to their Timeline and/or with friends.” He adds, along with a link to a help page, “If you find that people outside of your target audience are engaging with your post, it may be because they’re traveling through your targeted location. You can read about defining your location more specifically here.”

Could it be that Facebook responded to a customer complaint about bots chewing up his advertising rupees via a bot?

Online advertisers everywhere are fed up. In March, leading agencies in the UK banded together to suspend their clients’ YouTube ads, because too many were being displayed alongside extremist content. Google, which owns YouTube, was contrite.

“We deeply apologize,” said Google exec Philipp Schindler, “We know that this is unacceptable to the advertisers and agencies who put their trust in us. We’re taking a tougher stance on hateful, offensive, and derogatory content.”

In May the US trade publication Ad Age reported a gathering advertiser revolt. It cited industry analyst James McQuivey’s forecast that leading buyers such as Procter & Gamble will pull nearly $3 billion from social media buys and redirect their ad funds into safer channels in the next year.

The prospect of a plunge seems to have caught Facebook’s attention. Even as he announced record profits in November, CEO Mark Zuckerberg seemed fixated on dark clouds. You can hear the bottom line thud:

I’ve expressed how upset I am that the Russians tried to use our tools to sow mistrust…. We’re bringing the same intensity to these security issues that we’ve brought to any adversary or challenge we’ve faced.… Some of this is focused on finding bad actors and bad behavior. Some is focused on removing false news, hate speech, bullying, and other problematic content that we don’t want in our community. We already have about 10,000 people working on safety and security, and we’re planning to double that to 20,000 in the next year to better enforce our Community Standards and review ads…. I’m dead serious, and the reason I’m talking about this on our earnings call is that… it will significantly impact our profitability going forward.

Perhaps, then, the twin pincers of a bipartisan bill in Congress—titled “The Honest Ads Act”—and advertiser anger will prompt some badly needed innovation in defense against the dark arts. But just what can be done?

HUMANIZING AI

Zuckerberg and other tech leaders acknowledge that relying on people alone to review content won’t work. There’s just too much out there, and new accounts can be opened in the blink of a robotic eye. Artificial intelligence will have to play a role.

But the sad truth is that AI isn’t that smart. Most of us have been on a page with a “Captcha” feature that requires us to click the “I am not a robot” button. It’s a childishly simple task, yet it effectively deters bots. How much more difficult, then, is the task of spotting and zapping malicious content?

Efforts to date have failed. Twitter claimed to have fenced out voter-suppression memes like the text-to-vote one cited above, but on election day in Virginia this fall a similar lure ran for three hours on Twitter. Only after a Democratic official complained did Twitter take it down.

After Zuckerberg’s declaration of his company’s war on invidious content, Facebook remains littered with fakery. As the New York Times points out, much of it is easy to spot. Guys whose profiles have Anglo names and Midwestern hometowns but whose account names are Slavic and whose friends all live in Macedonia? Pretty good contenders to be bots or trolls.

AI’s failure to spot these comes as no surprise to Hsu, the neuroeconomist at UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business. “As humans, we intuitively understand the content,” he said, “but machines just aren’t very good at it.”

One problem, he thinks, is that tech giants have tried to engineer solutions. People continually find new ways to encode their prejudices, he notes, so “you can’t just remove terms like ‘neo-Nazis’ and you can’t ban all words.” Software programmers may be the wrong kind of people to try to endow AI with a grasp of human nature. Not because they are stereotypically nerdy but because they lack training in the relevant sciences.

Hsu and his collaborators have gone back to first principles in neuroscience and social psychology. It turns out that extracting just two axes of social perception—warmth and competence—enabled the team to devise a program that can learn how people stereotype others and turn their perceptions into social valuation.

They’ve tested a prototype repeatedly, first with undergraduates, then with a database of a broader population, and finally by feeding the entire content of Google into their AI. After all of that, Hsu says, their virtual machine can understand and interpret the social media world “kind of the way an eleven-year-old can.” It’s a lot better than anyone’s been able to do in the past, he says, but it’s not nearly as sophisticated as the people churning out hateful content. What’s more, the target is moving: like internet viruses, malicious social content continually evolves.

Human reviewers would appear to have job security for life. But if efforts like Hsu’s succeed, they can look forward to an effective ally—AI that will continually learn about people, as well as from the people it partners with, so that it can routinely make appropriate decisions with only a relative handful needing human intervention.

In the meantime, Facebook, Twitter, and other platforms remain heavily infected. How long will it take them to grow a healthy immune system? With national elections less than a year away, the answer could hardly matter more.