The Monster Hijacking Human Minds

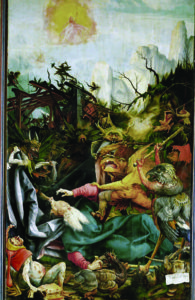

The Temptation of Saint Anthony by Matthias Grünewald, ca.1512-15

The Temptation of Saint Anthony by Matthias Grünewald, ca.1512-15 DEEP IN THE SWELTERING jungles of the Amazon, embedded within bird droppings, are eggs belonging to a nematode worm known as Myrmeconema neotropicum. Soon, ants from the species Cephalotes atratus will come along and take the droppings to their nest.

The ants feed the excrement to their larvae, causing them to inadvertently swallow the eggs. Inside each larva’s abdomen, the eggs hatch, and as the larva develops into a young ant, its occupants also begin to develop.

The nematodes change the ant. It begins to act like an outcast, regularly leaving the nest, wandering through the jungle on seemingly nonsensical routes. Its abdomen swells and becomes bright red like a berry. When the ant is ripe, it will even begin to act like a berry, sticking its abdomen in the air and falling still. A frugivorous bird will then flutter to the ant, and, thinking it has chanced upon a sweet morsel of fruit, devour it. When the bird next defecates, the cycle will continue.

I will now argue that this nematode worm’s life cycle is central to understanding every terrorist attack in history, and acquaint you with an invisible monster that hijacks minds and turns people into zombies. Somewhere within this argument, there may be a final cure for extremism.

For over a year I’ve been chasing jihadis in the town of Luton, England—often voted the UK’s worst place to live.

Among those I’ve investigated are the Westminster attacker Khalid Masood, the Stockholm bomber Taimour al-Abdaly, the leader of the toy car bomb-plotters Zahir Iqbal, the jihadi-turned-CIA-mole Morten “Danish” Storm, and the Buckingham Palace swordsman Mohiussunath Choudhury.

I visited their old streets and spoke to their neighbors. They generally said the same thing: “He was a nice man, quiet, polite, I just don’t understand how he could’ve done something like that…”

Sayful Islam talks to the press on his visit to Amsterdam, Holland. (Photo by Jan Kranendonk)

I approached Farasat Latif, a senior imam at the Luton Islamic Center, which counts among its former worshippers Storm, Masood, Iqbal, and al-Abdaly. I had a series of long conversations with Latif during Ramadan in June, and he told me much about Masood in particular, whom Latif got to know well at the center and also at a college funded by the mosque.

Latif told me he thought Masood had felt like an outcast, and that he was particularly touchy about race, feeling that being black separated him from his mostly Asian co-religionists. On one occasion, Latif and Masood visited Green Lane mosque in Birmingham to attend a talk. Masood was edgy throughout, glancing around, and when Latif asked him what was wrong, Masood whispered, “everyone here is Asian.”

Another time, Masood was in the local gym when he heard someone refer to him as “kala” (a non-derogatory way to describe a black person in Urdu). Masood apparently flew into a rage and attacked the man.

Digging deeper into Masood’s past, I discovered he had a long history of violence, much of it race-related. In August 1998 Masood (then known as Adrian Elms) was rejected by a woman and said that she didn’t like him because he was black. She stated it was his attitude and not his ethnicity. They argued, and Masood spat at her and punched her in the face. Two years later, Masood and a café owner got into an argument that apparently had racial overtones. Masood ended the argument by slashing the café owner’s face with a knife. His early life was filled with stories like this, in which he would lash out with paranoia at those around him, as though his pride were perpetually cornered.

Far-right demonstration in London, UK. (Photo by Elena Rostunova)

Masood is believed to have converted to Islam in prison. When he later moved to Luton in 2009 with his favorite daughter Aisha, who was recovering from a horrific car crash, he told Latif he had come to redeem himself from his troubled past and dedicate himself to Allah, whom he regarded as having mercifully spared his daughter’s life. This may be why it was in Luton that he fully abandoned his former name and assumed the Islamic Khalid Masood. Luton was apparently his intended chrysalis, from which he would emerge as a pure and devout Salafi Muslim. But he came to Luton at the wrong time, just as it was riven by tensions between the nascent far-right protest movement called the English Defence League and the terrorist group al-Muhajiroun, both of which were trying to incite a war between the town’s Muslims and non-Muslims.

The leader of Luton’s al-Muhajiroun cell was Mohammed Istiak Alamgir (aka Saif al-Islam: “The Sword of Islam”), a tempestuous street-demagogue with a beard forked like a serpent’s tongue. He would set up stalls outside Masood’s workplace and gym on Leagrave Road, and with his booming voice he’d tell passing Muslims that all non-Muslims were racists out to get them. He likened British Muslims to al-Ghurabaa (“the Strangers”)—noble outcasts presaged in Islamic prophecy to be oppressed and humiliated by infidels ahead of the “Hour” (the Islamic Day of Judgment).

What effect such a narrative had on Masood is unknown, but it’s not hard to imagine that he, an unstable, paranoid outcast, would’ve found appeal in a story of underdog misfits banding together and overthrowing the world that had tyrannized them.

Masood left Luton in 2013 and appears to have felt like an outsider to the end of his days (his final roommate in Birmingham mentioned how Masood never had visitors or left his flat). It’s likely that Masood’s perceptions of endemic racism and his inferiority complex, social awkwardness, berserk temper, and stifling isolation made him vulnerable to the delusions that in March 2017 compelled him to declare war on the West, killing four people and injuring fifty as he drove a car into pedestrians on the Westminster Bridge and near the Palace of Westminster in London.

A week before the attack, Masood is said to have told a family member (likely Aisha), “You will soon hear of my death, but don’t worry, be happy, because I will be in a better place, I will be in paradise.”

After the attack, Masood’s neighbors told me he was shy and polite. The tabloids, meanwhile, dubbed him “evil,” “a monster,” and “a beast.”

Using charged words to describe men like Masood is common because it’s easy. It requires no self-reflection and panders to one’s basest impulses, offering a license to reject nuance and indulge in the wild abandon of pure rage.

The problem is, when we make monsters out of people who commit monstrous acts, we dehumanize them and dramatize reality, goading the public into backlashes that are rarely restricted to the “monster” in question.

In Luton some of these backlashes have been violent, from beatings to arson. (Latif’s center was firebombed in 2009 by what are believed to have been far-right sympathizers.)

Mostly the backlashes have taken the form of acts of intimidation. In January 2016 the pro-Christianity, anti-Islam group Britain First (which gained recent notoriety when US President Donald Trump retweeted their propaganda videos) protested in my neighborhood, brandishing stake-sized crucifixes at local Muslims as though convinced they were vampires. The march had intended to scare Muslims away from Islam, but locals told me it only made them more sympathetic to Islamism. It’s not hard to see why; Islamism is built on the idea that non-Muslims are oppressing Muslims (just as Britain First is built on the idea that Muslims are oppressing non-Muslims). In short, Islamist hate begets far-right hate, which begets Islamist hate.

So how do we stop the hate?

The kind of hate we’re talking about is a reaction to perceived evil. The idea that some people are evil is rooted in a dualistic worldview that suggests we are spiritual beings, and that some people have good spirits and some bad.

In the periphery of Islamic folklore is the character Rocail, a son of Adam and Eve who, fearing that death would erase him, sought to preserve his legacy by crafting pearl statues that acted so convincingly like people that they were mistaken for having souls.

In fact, the idea of the soul itself may have been crafted to assuage the fear of death. In 2004 geneticist Dean Hamer identified a gene—VMAT2 (the “God gene”)—that appears to play a crucial role in religious thinking by controlling the levels of mood-regulating neurochemicals called monoamines, which are associated with belief. The God gene, and religion itself, may have developed as an evolutionary adaptation, providing humans not just with a blinker against death, but also a purpose to life. In our early history, a religious tribe would have been more organized, disciplined, and aggressive than a non-religious one in securing and allocating resources, allowing it to better ensure its survival and pass on its genes.

In the age of Netflix and chill, however, religion has lost its evolutionary benefits; it endures only as a relic of a former age, a psychological appendix. Further, its most common philosophical foundation (Cartesian dualism, which posits that souls exist and are separate from matter) has not effectively weathered advances in human thought, falling out of favor among most academics who now prefer the more empirically sound monist theory of physicalism (the idea that everything, including, people, are complex machines whose countless moving parts are the sole cause of their operation). Everything we know from science points to a determinist, physicalist universe (the supposed stochastic process at the quantum level has often been portrayed by spiritualists as disproving determinism, but in reality it does no such thing).

Determinism is such a powerful doctrine that it is even found in Islamic mythology. In the legend of Harut and Marut, Allah’s angels watched the folly of humans throughout history and dismissed them as losers. So Allah challenged the angels to live as humans on earth and see if they could fare any better. Two of them, Harut and Marut, accepted the challenge and reawakened on earth in human bodies, suddenly able to feel what humans feel. They soon lost the war against their senses, and fell into an abyss of hard drinking and hysterical sex. The moral of the story seems to be that we can only be what we are made to be.

The natural corollary of people being machines is that they are the sum total of their causes. Therefore, since their thoughts, impulses, and drives come from unthinking moving parts and electrochemical actions, they cannot have free will, if by free will we mean the ability to transcend determinism (i.e. to be more than your parts have intended for you).

The only logical argument for any kind of free will that we have is Daniel Dennett’s “Evitability” theory (from his book, Freedom Evolves), but this doesn’t actually refute determinism. In fact, it assumes it, and simply seeks to reconcile a physicalist worldview with a basis for personal responsibility.

So, the brain is not the seat of the soul, it’s just an extremely complex computer. And like all computers, it can be hacked. We see it at a micro-level with Myrmeconema neotropicum puppeteering ants. We even see it in mammals; Toxoplasma gondii makes mice flirt with cats in order to be consumed so it can complete its life cycle. This parasite appears to cause similar neurological changes in humans, making men more introverted and women more extraverted. It isn’t the only parasite that can affect human behavior; the rabies virus, for example, has long been known to make people aggressive.

So, if parasites can hack humans, why can’t ideas? Richard Dawkins’s meme theory posits that ideas can be considered psychological genes in that they are bound by the strictures of natural selection. If we take this concept further, we can theorize that popular ideas spread like psychological viruses, using minds instead of cells to spread copies of themselves; hence the term “going viral” to describe a meme that blows up on the internet.

Slender Man (LuxAmber | Wikimedia Commons)

But, we could go even further. We could posit that certain ideas can be considered, for all intents and purposes, actual, literal parasites of the mind.

Let’s take one particularly chilling case. Slender Man is a creature of folklore with a featureless face and gangly limbs. It first appeared in June 2009 in an online Photoshop contest, where users had to edit mundane pictures to make them appear supernatural. One user added a spectral figure to pictures of children, and added captions like this:

We didn’t want to go, we didn’t want to kill them, but its persistent silence and outstretched arms horrified and comforted us at the same time…

—1983, photographer unknown, presumed dead.

The pictures and subtitles quickly captured the imaginations of the other forum users, who added their own details to the mysterious Slender Man and made it go viral.

Within weeks, a substantial mythology around Slender Man was sprawled across the internet in the form of short stories, gifs, drawings, YouTube videos, mobile games, and “creepypastas.” Portrayals varied, but Slender Man was generally described as an otherworldly being that targeted children, making them commit horrific acts of violence in its name. As the legend grew, it took on the form of urban myth, with many wondering how such a specific concept had developed such ubiquity if it wasn’t rooted in reality.

By 2014, Slender Man had escaped the world of meme and contaminated mainstream culture, spawning characters on TV shows and video games. That summer, Slender Man entered the real world, invited in by two twelve-year-old Wisconsin girls who made it an offering. The offering was their friend, whom they lured into the woods and stabbed nineteen times. They said they couldn’t escape Slender Man.

The following month, a woman in Ohio was allegedly attacked by her daughter, who wore a mask and hood, and wielded a knife. She had apparently been writing stories about Slender Man. A few months later, a Florida girl set her house on fire while her mother and brother were inside. She had been reading online about the sinister figure. In 2015, Slender Man was even implicated in a string of suicides on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota.

In essence, Slender Man became so influential that it became real. The mythology of Slender Man acted like Slender Man, exhorting young children to commit incomprehensible violence. And as its influence seeped into the real world, its legend grew even stronger. It was as though it were literally feeding off our nightmares to coalesce and reify.

In other words, the idea of Slender Man effectively behaved like a psychological parasite, invading host minds and irrevocably changing them for its own “end.” The idea itself lacked physical form, but when adopted by a mind it mutated the brain’s material structure, distorting its vista of reality.

The precise mechanism by which thoughts rewire the structure of the brain is only beginning to be understood. It’s not something that happens quickly but in gradations, through a process known as Hebb’s rule, whereby neural connections grow stronger the more they’re used. Or, as Hebb put it, “neurons that fire together, wire together.” Thus, a belief becomes more believable the more it’s believed—delusion becomes self-reinforcing—because ideas affect thoughts, which affect neural pathways, which affect openness to ideas.

But even if an idea can change the physical structure of a brain, surely it cannot be a parasite for the simple reason that it’s not an organism. In fact, parasites don’t have to be alive: a virus is little more than a strand of genetic material inside a protein shell. But when the virus enters a host and hijacks a cell, it ceases to be dormant. It begins to act as the cell’s own genetic material, effectively becoming the cell and gaining life through it.

Similarly, an idea like Slender Man is unconscious outside a host but gains sentience when it hijacks a human mind and twists it into a killer’s, becoming conscious through it in an effort to continue the cycle of fear and spread the myth to other minds.

Just as Slender Man nourishes itself on fear, extremist ideologies such as Islamism and ultranationalism nourish themselves on hate. However, the myth by which they elicit emotions and parasitize minds is much more intricate, much more convincing, and therefore much more virulent.

Newspaper headlines the day after the terrorist attack in Westminster, London, in which Khalid Masood killed at least three people. (Photo by Lenscap Photography)

To illustrate how extremist ideologies behave like parasites, let’s look at the parallels between the cycle of hate in my neighborhood and the life cycle of the nematode I mentioned at the start of this article, Myrmeconema neotropicum:

When an ant is infected with the nematode, it begins to act in ways that make it look like a berry; when a person is infected with hate, he begins to act in ways that make him look like a monster.

The bird confuses the ant for a berry; the media confuse the extremist for a monster.

The bird defecates nematode eggs; the media defecate spook stories.

Ants feed on the bird’s shit to become filled with nematodes; people feed on the media’s shit to become filled with hate.

The nematodes will soon infect another ant, propagating the life cycle; the hate will soon infect another person, propagating the strife cycle.

As you can see, the analogy works. We can coherently view violent extremists not as monsters but as mere hosts of the true monsters: parasitic ideologies that invade damaged individuals and work through them to create more damaged individuals, and more copies of themselves.

As I said before, if you come to Luton and ask, as I have, about the many locals here who became terrorists, you’ll always get the same answer: “He was a nice man, quiet, polite, I just don’t understand how he could’ve done something like that.”

The probable reason they don’t understand is that they regard humans as split between good souls and bad. If they instead regarded terrorists as mammals infected with a parasite, then suddenly they’d understand, because when you view the true enemy as the parasitic ideology and not the individual, suddenly everything about jihadism makes sense: the fact that ISIS can effortlessly shift forms between solid (caliphate), liquid (insurgency) and gas (idea); the fact that a rise in far-right nationalism correlates with a rise in Western Islamism; the fact that killing terrorists often creates more terrorism.

All of this is easily explained within the context that jihadism is an ideological parasite. It spreads by convincing people that there must be a war between Muslims and non-Muslims. Whenever someone’s mind becomes infected, the parasitic ideology causes them to commit acts which increase enmity between Muslims and non-Muslims, thereby making the ideology more convincing and better able to infect other minds—a positive feedback loop, a Hebb’s rule of hate.

The far-right parasite works much the same way, but mostly targets young white males and operates through ultranationalist groups like Britain First. This parasite is not at war with the Islamism parasite—it is in symbiosis with it, for they both conspire to sow enmity between Muslims and non-Muslims.

Therefore, if we are going to defeat extremism, conventional strategies won’t work. We have to see it for what it is—an epidemic of parasitic infections that feeds on our revulsion and hate.

Some will argue that regarding extremists as biological vectors rather than malicious individuals confiscates their agency and deflects their responsibility, allowing them to weaponize victimhood.

In reality, regarding terrorists as victims of a parasitic ideology doesn’t absolve them of responsibility—it merely seeks to explain why they failed to uphold it. Personal responsibility is something that must be imposed on individuals irrespective of the truth, because holding people responsible deterministically makes them act more responsibly. But if they fail in their duty to safeguard their sanity for whatever reason, they should be treated as victims because that is what they are. If a jihadi terrorist were perfectly rational, he wouldn’t choose to subject himself to a jihadi ideology. He is therefore a victim of the vulnerabilities of his own mind, and undeserving of hate.

On the other hand, if we continue to see extremists as monsters, then we really will be absolving them of responsibility, because using good or evil as an explanation is the very epitome of essentialism. If someone is evil, they are doomed to commit evil acts; if they later became good, they wouldn’t be truly evil.

The mistake of seeing evil as something inherent to certain individuals is shared by all extremists, left, right, and Islamist. In fact, it could be argued that much of the world’s violence comes from seeing others as inherently evil and therefore irredeemable and unworthy of life. By allowing ourselves to become vessels of hate, we allow the parasite to work through us, furthering the divisions between Muslims and non-Muslims, and thereby making the West-versus-Islam narrative more convincing so that it can better spread to other minds.

So how do we stop it? The usual way to kill off a parasite is to break its life cycle. Myrmeconema neotropicum would soon go extinct if birds learned to tell the difference between berries and bloated ants. Likewise, extremist ideologies would eventually die out if people learned to tell the difference between monsters and madmen. Firebombed mosques and vehicular rampages wouldn’t yield enough rage to sustain hateful ideologies if everyone knew they were acts of spontaneous insanity rather than organized evil.

The solution to extremism, then, is to spread the ideas in this article as virally as possible—to teach everyone that concepts can hijack minds and make people ill. But first we’ll have to address a stubborn fact; that the people we most need to convince—sympathizers of groups like al-Muhajiroun and Britain First—share the same, simplistic view of reality, in which Adam and Eve gained knowledge of good and evil not by rigorous debate or profound reflection, but by eating a piece of fruit.