If Social Media Is Making Us Worse, Can We Make It Better?

SOCIAL MEDIA IS BAD. It takes your worst parts—your vanity, your ignorance, your credulity—and makes them even worse. It weakens your ability to focus. It distracts you while you drive. It makes you hate people you should feel unity with and envy people you should find insufferable. It turns you into an addict, which, as Jaron Lanier emphasizes in his latest book Ten Arguments for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now, makes you not only dependent on something outside yourself—something you can’t control and that replaces your moral well-being as the center of your thinking—it also makes you more nervous, more panicky, more reflexive, more paranoid, and more distracted. That addiction is fed by fear, hatred, and contempt—the parts of you that fall for the cheap laugh, the cheap sneer, the cheap point, the cheap victory.

SOCIAL MEDIA IS BAD. It takes your worst parts—your vanity, your ignorance, your credulity—and makes them even worse. It weakens your ability to focus. It distracts you while you drive. It makes you hate people you should feel unity with and envy people you should find insufferable. It turns you into an addict, which, as Jaron Lanier emphasizes in his latest book Ten Arguments for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now, makes you not only dependent on something outside yourself—something you can’t control and that replaces your moral well-being as the center of your thinking—it also makes you more nervous, more panicky, more reflexive, more paranoid, and more distracted. That addiction is fed by fear, hatred, and contempt—the parts of you that fall for the cheap laugh, the cheap sneer, the cheap point, the cheap victory.

That so many books have been written about social media and make the same points above without drawing the obvious conclusion from them—that social media is a net negative on our lives—shows not the weak will or complacency of their authors but the recognition that however bad social media is, it’s also here to stay.

As Douglas Rushkoff puts it in Team Human (due out January 2019), there’s no way of returning to a pre-digital era: “We can’t go back; we must go through.” Even those with a reputation for being anti-social media (or even anti-internet) tacitly accept that social media is here to stay. Technology writer Nicholas Carr has called for a counter-cultural movement against the digital status quo, but counter-cultural movements only offer a degree of separation from the status quo and are eventually co-opted and commodified by it.

In Ten Arguments Lanier encourages readers to delete their social media accounts for at least six months—so that you develop a fuller sense of self and therefore better “resist the easy grooves they guide you into”—and for social media platforms to change their business model from “behavior-modification empires” (free access so the platforms make money by spying on and manipulating you) to fee models the likes of Netflix and HBO. With that fee model came what’s called “Peak TV,” and Lanier thinks with it we can get “Peak Social Media.” And he’s probably right. That business model would very likely make for a better social media experience. But it would also keep many of the worst things about the current business model and just make them less obvious. It would encourage the TV equivalent of product placement over commercials. Which is better than what we have but not qualitatively better.

Ten years ago it was a journalistic fad to write about how criticism of social media (and smartphones) was overblown. How everything we thought was bad about it was actually good or at least not that bad. Sam Anderson’s frequently cited New York Times Magazine article from 2009, “The Benefits of Distraction” (which says, among other ludicrous things, that if Albert Einstein and The Beatles were around today, they would’ve been even more innovative because of new technologies), now reads more like a fatalistic surrender to the social and economic power of Silicon Valley than it does as a “hot take” against prevailing wisdom about digital addiction.

“There’s pretty much no one left who dismisses criticism of social media as just another moral panic or just the latest fear-mongering bout technology.”

Conversely, nowadays almost no one—especially not social media users—would disagree with the assumption that social media is making people worse. Some might object that all social media platforms are equally culpable or give different reasons for why they think social media is having the effect it is. But there’s pretty much no one left who dismisses criticism of social media as just another moral panic or just the latest fear-mongering about technology. However, even with the general agreement about the downsides of social media, there hasn’t been a mass exodus from platforms. Why not? Because everyone has a reason to stay. Facebook is how we see pictures of our nephews. Twitter is our newsfeed. On YouTube we can find lectures on any topic we want and watch concert performances of the world’s best musicians and bands. Some people are straightforward and say they wish they could get off social media. But they can’t, because social media is designed to be addictive—and it is.

There are plenty of good reasons for staying on social media. And most of them are true. Some of the previous examples are from my own life. I use Twitter as a newsfeed and watch old boxing matches and lectures on YouTube. I even met my wife through social media. I’d be an idiot to deny the positive effects social media has had on my life and character.

Still, I have to leave my phone off during the day; otherwise I won’t get anything done. I feel more anxious and frustrated after spending time on social media. More importantly, I’ve seen what social media has done to friends and family. I see how it’s scripted and automated thinking. How it’s made it that much easier for centralized power to control what gets attention and what doesn’t. How it leaves people “pre-angry” (to borrow Matt Taibbi’s word for it): ready to react, unable to think.

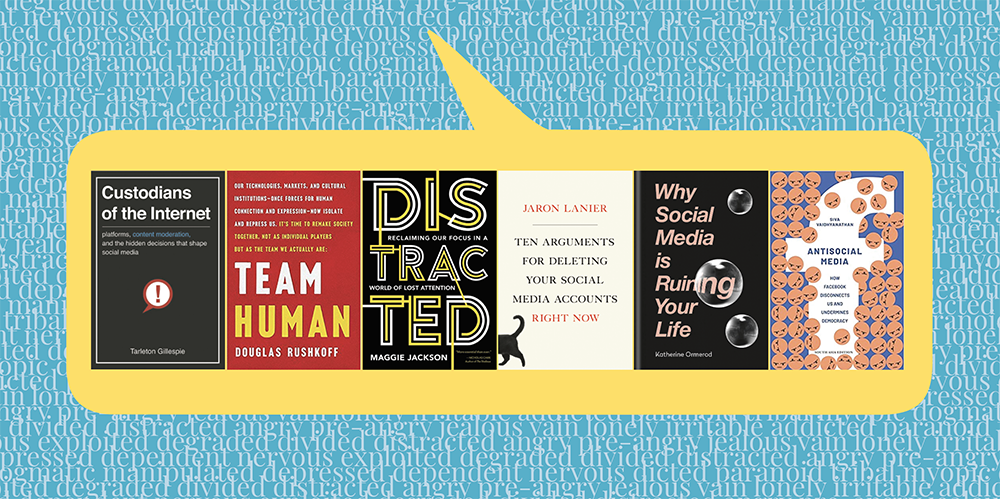

There have been over a dozen books published just this year that show how social media brings out our worst impulses. Suicide, inequality, ignorance, hatred, fraud, depression, drug use, loneliness, obesity—pick your indicator of human misery and there’s likely a study cited in one of these books showing its linkage to social media. Some of these books focus on the personal and psychological consequences of social media use. For example, Why Social Media is Ruining Your Life by Katherine Ormerod looks at how social media negatively affects the mental and emotional health of women. Maggie Jackson’s Distracted: Reclaiming Our Focus in a World of Lost Attention (an updated edition of her 2009 book) looks at how social media—and the digital age in general—is destroying our self-control, which in turn destroys our ability to think critically. Others are more political. Antisocial Media: How Facebook Disconnects Us and Undermines Democracy by Siva Vaidhyanathan is about the active role Facebook has played in debasing our politics. A chapter in Tarleton Gillespie’s Custodians of the Internet: Platforms, Content Moderation, and the Hidden Decisions that Shape Social Media covers how platforms’ “community guidelines” are weaponized to censor and ban political enemies. Others—such as Lanier’s Ten Arguments and Rushkoff’s Team Human—try to look at both the personal and the political and show how the two aren’t separable: in fact, they’re intricately linked and each exacerbates the other.

Now, while almost everyone agrees that social media is making the world worse, there are still a few technology critics who feel that social media is becoming a scapegoat for reality. For example, Carr ends his own review of Vaidhyanathan’s Antisocial Media and Lanier’s Ten Arguments by saying, “The problem with Facebook is not just Facebook. It is also us.” Which is true. Facebook didn’t spread the rumors about Rohingya Muslims that has led to the terror campaign against those people by the Burmese government; authoritarians and bigots on their platform did. Facebook didn’t turn the United States into a racist and gullible country; and Russian trolls might’ve excited that racism but it’s always been there. No platform is forcing your boss to spy on you or some third-party business to manipulate you; they’re doing that because of already existing power relations and incentive structures.

But the issue with social media isn’t that it’s directly manifesting these things; rather that it’s making the manifestation of these things so much easier. Social media didn’t turn people into dopes—a whole host of things did that—but social media gives liars and charlatans direct access to those dopey minds (and smartphones make that access ubiquitous).

And this applies to all the other things social media is making worse. Addiction is as much an effect of unhappiness (or, more precisely, dissatisfaction) as it is a cause. So addiction has as much to do with the subject as the object. But with the advent of social media and smartphones, those vulnerable to addictive behavior now have a socially acceptable form of addiction that they’re socially obligated to carry with them whether they’re already addicted or not. Social media finds you lost in the woods and takes you even further from the beaten path.

“As the saying goes, if you’re getting something for free, you’re the product. With BUMMER businesses, your attention is the product, and they aren’t just collecting data to manipulate us as customers, they’re also doing it to replace us as producers.”

Ten Arguments insists that neither the internet as a whole nor the “core” of social media is to blame. What’s to blame, according to Lanier, are the “structures” social media companies have built in order to make money. He calls it the BUMMER business model, which stands for “Behavior of Users Modified, and Made into an Empire for Rent.” A BUMMER business offers you a free service—with Facebook, access to the platform; with Google, free use of the search engine—and in exchange that business gets to collect data about you. And not just when you’re using their service. Facebook, for example, collects data about you from websites that have the Facebook “Like” button (even if you’re logged out of your Facebook account or don’t even have one).

Initially, BUMMER businesses made money through advertising and by selling people’s data to third parties. A leaked Facebook memo bragged to potential advertisers that the social media company had enough data on its users to correctly predict their emotional state at any given moment. Indeed, the companies analytics are so precise and intrusive that it has targeted female users who are about to begin their menstrual cycles with fashion advertisements. And as Jackson stresses in Distracted, surveillance always leads to manipulation. And that’s what we see now with BUMMER businesses. Third parties now are paying to not only spy on you but to use what they learn to manipulate you.

As the saying goes, if you’re getting something for free, you’re the product. With BUMMER businesses, your attention is the product. BUMMER businesses want you as “engaged” as possible on their platform, which means having you scroll through endless feeds, wander to new pages, watch automatic next videos, post comments, and like (or dislike) other users’ comments.

What’s the best way to keep someone’s attention? One obvious way is to show people what they want to see: pictures of family, cheap tickets to local events, articles that validate their beliefs. Another way, however, is to show them things they hate. Or to show them things they hate being hurt or humiliated. Or to show them the most absurd or cringe-inducing representation of the thing they hate. (How many views does “Stupid Feminists Get Roasted Compilation #12” have?) As our ability to focus shrinks, the good doesn’t hold our attention as well as the bad. So, rather than show us the best representation of things we disagree with, BUMMER businesses show us the worst. Now the “hideous ecstasy of fear and vindictiveness” of Nineteen-Eighty Four’s Two Minutes Hate is always available at the click of a button.

Lanier sees two things especially wrong with this way of holding our attention. First, with these customized feeds none of us are seeing the same thing, so we don’t have a sense of what it takes to communicate with one another. “Your understanding of others has been disrupted,” Lanier writes, “because you don’t know what they’ve experienced in their feeds, while the reverse is also true; the empathy others might offer you is challenged because you can’t know the context in which you’ll be understood.” Again, social media didn’t create myopia and dogmatism, but it has made them worse.

“Perpetual outrage is exactly what social media platforms want, because outrage means perpetual engagement.”

Which leads to the second thing Lanier finds wrong with the BUMMER model. Not only does it narrow and intensify negative impulses, it also favors the most “irritable, authoritarian, paranoid, and tribal” points of view. As Lanier puts it, “The BUMMER model doesn’t drive politics right or left, but down.” Because attention is the primary value on most platforms, and the best way to get attention is through “controversy,” “ordinary people tend to be come assholes.”

I’m not sure I agree with Lanier when he says the BUMMER model doesn’t drive politics in any particular direction except down. It might drag everything down, but some beliefs and prejudices are more susceptible to that downward pull than others. It isn’t a coincidence that the top ten shared stories on Facebook are always from right-wing websites. Over the last half dozen years there’s been a resurgence of right-wing authoritarianism—much of which has gained power and popularity directly through social media.

The Philippines’s Rodrigo Duterte was crowned the “undisputed king of Facebook conversations” during his 2016 presidential run. The leader of Italy’s Five Star Movement thanked god for Facebook. A Brazilian marketing firm was paid to create millions of Whatsapp accounts to spread lies about Jair Bolsonaro’s political opponents. Lies like that when he was mayor of São Paulo, the Worker’s Party candidate Fernando Haddad gave schools penis-shaped baby bottles to combat homophobia, or that he had published a book in favor of incest, or that his running mate had tattoos of Lenin and Che. For the 2016 presidential election, Facebook helped the Trump campaign maximize its use of the platform (Facebook offered to help both campaigns, but the Clinton campaign passed). The political data-mining company Cambridge Analytica—partially owned by Robert Mercer, one of the billionaires who pays for right-wing grifters to yell about “SJWs” and “political correctness”—used “targeted advertising” based on thousands of data points to help get Trump elected.

The Philippines’s Rodrigo Duterte was crowned the “undisputed king of Facebook conversations” during his 2016 presidential run. The leader of Italy’s Five Star Movement thanked god for Facebook. A Brazilian marketing firm was paid to create millions of Whatsapp accounts to spread lies about Jair Bolsonaro’s political opponents. Lies like that when he was mayor of São Paulo, the Worker’s Party candidate Fernando Haddad gave schools penis-shaped baby bottles to combat homophobia, or that he had published a book in favor of incest, or that his running mate had tattoos of Lenin and Che. For the 2016 presidential election, Facebook helped the Trump campaign maximize its use of the platform (Facebook offered to help both campaigns, but the Clinton campaign passed). The political data-mining company Cambridge Analytica—partially owned by Robert Mercer, one of the billionaires who pays for right-wing grifters to yell about “SJWs” and “political correctness”—used “targeted advertising” based on thousands of data points to help get Trump elected.

Lanier is right when he says, “since social media took off, assholes are having more of a say in the world.” Until very recently, the alt-right pretty much dominated the political spaces of social media. And that’s not an accident or a coincidence. The alt-right exists as an oppositional force. Its politics are just opposition to cultural liberalism. That is, it’s just for or against something based on whether or not “cultural Marxists” are for or against it. That’s one of the reasons why the alt-right can seem ideologically heterodox. Because a lot of ideological tendencies can oppose, say, gay marriage and hide behind “owning the libs.”

This oppositional kind of politics requires perpetual outrage. One always has to be finding something the other side is doing that is ridiculous or pathetic. (And if alt-right media figures can’t find anything, they’ll just manufacture something, such as hire fake protesters to interrupt a speech.) And perpetual outrage is exactly what social media platforms want, because perpetual outrage means perpetual engagement. The BUMMER business model might bring all politics down, but it structurally favors politics that depend on persuasion over truth and negative emotion over moral scruple. And that kind of politics is found on one side more than the other.

Both Lanier’s solutions—everyone leaves social media, at least temporarily, and big platforms switch from the BUMMER model to a pay-for-access one—seem implausible. You might be able get a few thousand people to leave Twitter or Facebook, but how many people can you seriously expect to stop using Google? And the big platforms are simply making too much money from their “behavioral-modification empires” to change how they make that money. Not to mention that they like the BUMMER model not just for the cash it brings in but for the power it gives them. Lanier is probably right when he says that not being on social media doesn’t doom you to irrelevancy. But it can feel that way—especially if you run a business or you’re self-employed. What’s more, knowledge is power, and with the BUMMER model these big platforms have an institutional incentive to accrue more and more data about users. We offer them knowledge about ourselves for free, and they gladly take it.

The lack of viable solutions isn’t just an issue for Ten Arguments. In fact, of all the solutions I came across, Lanier’s are the most plausible and have the most potential to be impactful. Jackson says we need a “renaissance of attention,” but she never gives much detail on what that means. Gillespie, partly limited by his subject matter and scholarly approach, gives a list of proposals to make social media moderation more meaningful and effective (more human moderators, more transparency by platforms on their moderation apparatus, more experts on online culture, etc.), but these changes would only further the “arms race” between platforms and “bad actors” (to use Lanier’s phrases). Ormerod gives some helpful tips for social media etiquette—”Take your emotional temperature,” “Listen more than you tweet”—but those tips assume everything about platforms staying the same except for how we personally conduct ourselves on them.

The “no viable alternative” criticism of books on politics and society is usually a cheap and lazy one. Most authors are thinking things through as they go along and, at best, hope to get you thinking about those things too—or, if you were already thinking about them, get you to think about them a little differently. Which is why most alternatives you find in such books are tentative, vague, and brief. And if they’re not, that’s usually because they’re not really alternatives but just projections of existing trends.

However, I think most of the books on social media I read lacked viable solutions because they didn’t frame the problem correctly. Rushkoff in Team Human probably comes closest. He sees that it’s not just personal irresponsibility or the “structures” of social media that are to blame, but the “core” itself. And the core of social media is also the core of our entire economy. BUMMER businesses aren’t just collecting data to manipulate us as consumers, they’re also doing it to replace us as producers. So you have Uber using drivers’ data to make algorithms for self-driving cars and Google using the translations people do online to update Google Translate.

Lanier also acknowledges this, but his solution is to commodify what people do on the internet. To treat data as labor. So, if someone wants to use your data, they have to pay you for it. Which is fine until BUMMER businesses collect enough data to completely replace humans with algorithms. (To be fair, Lanier indirectly addresses this point in another book and is probably right that some algorithms, such as translation algorithms, won’t be able to replace humans because language is always changing.) But to treat data as labor leaves it with all the economic injustices of regular labor compensation. Rushkoff’s solution bypasses this by saying labor should get you not just money but ownership; Uber drivers who are producing all the data used to build self-driving car algorithms should get partial ownership over those algorithms. This way of thinking doesn’t just challenge BUMMER businesses though, it challenges capital-labor relations everywhere. In the 1930s, German social philosopher Max Horkheimer wrote, “If you don’t want to talk about capitalism then you had better keep quiet about fascism.” Rushkoff seems to be indicating something similar: if you don’t want to talk about capitalism, then you had better keep quiet about social media.

As sympathetic as I am to that, it obviously doesn’t fix most of the ways social media is making us worse. Because not only is social media exploitative, it’s also degrading. As Rushkoff says, it replaces truth with vitality. Truth always takes a hit from new communication technologies—a popular example being the mutual advent of fascism and radio in the early twentieth century. Still, Rushkoff’s “platform cooperatives” plus Lanier’s pay-for-access business model would unquestionably make for a better social media experience. Platforms could no longer play so fast and loose with user data, and the problem of fake accounts, fake reviews, and fake groups would be somewhat curtailed.

In 1992, science fiction writer Bruce Sterling said people liked the internet because “there is no Internet Inc. There are no official censors, no bosses, no board of directors, no shareholders.” Well, it’s got all those these things now. Technology critics like to blame the “democratization of the web” (where everyone has a voice) for the deleterious effects of social media. But what democracy? Plenty of people might have a voice, but few still have a say. Again, social media didn’t make us vain, credulous, or susceptible to addiction, but it has made all those things worse and made a lot of money for a few executives and shareholders in the process. It might seem like a great paradox that with everyone now having a public voice, the range of opinion and expression has increasingly narrowed. But reading the New York Times recent exposé on Facebook—how the company’s executives used one lobbying firm to spread the lie that criticism of the social media giant was rooted in anti-Semitism and another that it was rooted in a George Soros-led conspiracy (an anti-Semitic trope)—it’s easy to see just how centralized opinion-making still is.

The horror genre is always a good indicator for the collective fears of a society, and it’s not surprising that more and more horror movies have social media at the narrative and thematic center of their stories. Because what we find on social media is terrifying: the regimentation of thought, the degradation of spirit, political outrage as a distraction from political change—concentrated versions of what’s wrong with our society and ourselves.