John Muir’s Radical Religion of Beauty

“The mountains are fountains of humanity as well as of rivers, of glaciers, of fertile soil. The great poets, philosophers, prophets, able people whose thoughts and deeds have moved the world, have come down from the mountains—mountain-dwellers who have grown strong there with the forest trees in Nature’s workshops.”

—John Muir, Alaska Journal, June-July 1890

I HAD ALREADY BEGUN my pilgrimage out of faith, preparing to leave the ministry, when I decided to make another kind of pilgrimage back to Scotland and the boyhood home of the great naturalist John Muir in Dunbar, near Edinburgh. I had read Mountains of California (1894) while snowshoeing in Hope Valley above Lake Tahoe and thumbed through his reproduced journals like secular scripture while climbing trees in the watershed near my home across the bay from San Francisco. I was converted to Muir’s worldview—his fundamentally humanist philosophy rooted in nature.

Collecting salient selections from his writings into a little book of “meditations,” I read them at his family home in Martinez, California, at the Sierra Club’s LeConte Lodge in Yosemite Valley. I read them again, at the invitation of the chief park ranger, under the magnificent cathedral of redwoods in Muir Woods National Monument in Mill Valley, California. Later I penned a novella imagining the wondering naturalist meeting a youthful, wandering Nazarene.

The question I’m asking now is whether we might consider John Muir one of our humanist heroes, perhaps even going so far as to dub him a “secular saint.”

“Wildness is a necessity,” the Sierra sage wrote in 1901, on the first page of Our National Parks. Indeed, we do need wildness as creatures of wilderness—though we deny it, fear it. In his lecture “Walking” (published as an essay in 1862) Henry David Thoreau had famously said, “In Wildness is the preservation of the World.” Muir took this a step further, literally. He took his mentor’s statement as a map, since Thoreau prefaced his famous words with “The West … is but another name for the Wild.” Muir turned his face to the Western mountains and discovered a radical religion-beyond-religion in the “fountains of humanity.”

Throughout my own years of religious study, I read saints, mystics, theologians, biblical scholars, philosophers—digging around for wisdom wherever I might find it. As an ordained minister and chaplain, I taught classes in churches on world religions, sacred scriptures, and wisdom teachers across the spiritual landscape, reading delightful stories from Hasidic Jews and Sufi Muslims, Zen Buddhists and Native Americans, Native Africans, Catholic and Protestant Christians, and more.

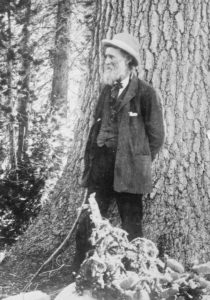

Source: Chris Highland

Then, out of the wilderness, the bearded and bewitching John Muir sauntered down the trail (“saunter,” as Thoreau defined it, is a deep walking through the “holy land”—and all land is revered by a saunterer). Muir didn’t “hike”—he sauntered.

Muir understood that religion, like humanity itself, too often fears the wild where it originated. With dry tea, a chunk of bread, and curiosity in his pockets, John Muir fearlessly entered the wildnerness and emerged like Moses from Sinai, Buddha from the Indian forest, Jesus from the Judean desert, Muhammad from the Arabian cave (and like Galileo Galilei from his telescope or Charles Darwin from his microscope). Yet—and this is crucially important—Muir was no prophet calling “Come unto me.” His secular gospel was to go, not come. In essence, he shouted: “Go saunter into the great classroom—the greatest temple!”

Akin to classic prophetic traditions, he called for us to awaken, to leave our heavy theologies and holy books, to lighten our packs and risk an unpredictable journey, a challenging adventure. He pounded the pine-scented pulpit or lichen-laced lectern: “Go!”

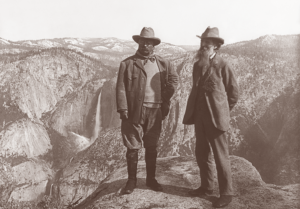

Muir is remembered, appropriately, as the patriarchal parent of our National Parks, first president of the Sierra Club, mountaineer, explorer, and expert on glaciers. As his writings brought him fame and influence, he slept in the snow under the stars with President Theodore Roosevelt, sailed in Alaskan fjords with fellow naturalist John Burroughs, and fought a political fight to preserve wilderness like his treasured Hetch Hetchy Valley near Yosemite. He was much more than a conservationist, in the sense that the earth is not something to conserve—to “use” as a “resource”—but our home to preserve. Muir was a preservationist. If he were around today, “Keep Wilderness Wild” would be his bumper sticker—if he drove a car.

Unlike Moses, Muir descended from the mountaintop a secular, naturalistic evangelist, and as a good scientist welcomed verification of what he experienced.

Source: Library of Congress

When I initially read My First Summer in the Sierra (1911), I thought it sounded almost like mysticism, spoken by some ancient saint or sage—almost “spiritual” without being preachy. In it, Muir is describing our world, fully accessible to me, to anyone, and I know what he says is true because I’ve been there. Hiking in Yosemite, snowshoeing among the ancient sequoias and gnarled junipers, you can breathe in the alpine air and touch the same trees, delighting in the same wildflowers and granite crags he did. Standing in the refreshing mist of cool cascades, Muir seems present in the mists of time. It’s as if he’s on the trail beside us, teaching at every step in the open-air classroom.

On a hot July day above Yosemite Valley he scribbles in his tea-stained journal:

Every hidden cell is throbbing with music and life, every fibre thrilling like harp strings, while incense is ever flowing from the balsam bells and leaves. No wonder the hills and groves were God’s first temples, and the more they are cut down and hewn into cathedrals and churches, the farther off and dimmer seems the Lord himself. The same may be said of stone temples.

Every cell pulsates with life in Muir’s congregation; every hill, every forest is a temple. With a leap of joy rather than a leap of faith, he’s ascended above the clouds of orthodoxy to discover the bubbling, babbling springs of humanity.

When he has a strange experience in the mountains, sensing the presence of a professor from his University of Wisconsin days in the valley below, Muir runs down to find his kindly teacher on the trail. Reflecting on this unusual event he writes:

It seems supernatural, but only because it is not understood. Anyhow, it seems silly to make so much of it, while the natural and common is more truly marvelous and mysterious than the so-called supernatural. Indeed, most of the miracles we hear of are infinitely less wonderful than the commonest of natural phenomena, when fairly seen.

This reasonable, common-sense response is strong evidence for Muir’s natural humanistic perspective. His innate skepticism is time and again revealed in a careful choice of words, though he often uses religious terms familiar to his readers. For instance, he still speaks of God, yet what have the mountains taught him? Not that an invisible deity is commanding obedience from burning trees. And certainly not that a strict father in the sky is killing his own child on a bloody tree for his own satisfaction. There’s nothing natural about any of that.

Muir rooted his sauntering faith in this world and no other. His oft-repeated exclamation, “Glorious!” wasn’t directed to a deity but to the uncontrollable creations of nature.

Muir’s lord is absolutely visible, revealed in the creative forces of nature. Is this pure pantheism? Perhaps. But I think more. His divinity is palpable, incarnate as rain, ice, fire, and wind, actively sculpting and creating an evolving earth. Yes, nature and God are one, yet beyond anthropomorphic representation or anthropocentric hubris.

How do we begin to understand Muir’s nature God? In one of the most significant entries in his journals, Muir asserts that “no synonym for God is so perfect as beauty.” This is central and essential in understanding Muir’s use of religious terminology minus the theological stickiness. Let any concept of “God” slip away; natural beauty is the incarnation of the cosmos minus any transcendence to a “better world” for which no evidence exists.

Consider Muir’s view of the Bible. He respects the ancient book, but speaks of much more ancient pages—“nature’s Bible”—written in the mountain ranges, especially in Alaska and his beloved “range of light,” the Sierra Nevada.

US President Theodore Roosevelt (left) and John Muir, founder of the Sierra Club, on Glacier Point in Yosemite National Park. In the background: Upper and lower Yosemite Falls. (Source: Library of Congress)

As a boy in Scotland, Muir’s evangelist father forced him to memorize large portions of the Bible. He always carried that book in his brain, but he carried Robert Burns in his heart, singing the poet’s ballads to squirrels and birds in the highlands of California and beyond. “Wildly here, without control, nature reigns and rules the whole,” wrote Burns, his beloved Scottish kinsman. And so, Muir rooted his sauntering faith in this world and no other. His oft-repeated exclamation, “Glorious!” wasn’t directed to a deity but to the uncontrollable creations of nature.

Humanism’s environmental concern is neatly summarized in the excellent “Ten Commitments,” recently introduced in the Humanist (September/October 2019) by Kristin Wintermute. “Humanity is also capable of positive environmental change that values the interdependence of all life on this planet,” the commitment to environmentalism contends. It’s a hopeful, practical, inclusive vision shared by the man many know as “John of the Mountains,” who, in A Thousand-Mile Walk to the Gulf (1916), wrote: “The universe would be incomplete without man” (what he would today rightly term humankind); “but it would also be incomplete without the smallest transmicroscopic creature that dwells beyond our conceitful eyes and knowledge.”

What does Muir say about religion itself? How organized can faith be, when we are born and baptized in wildness? True religion, he would agree, cannot be found in an artificial “house of God,” nor can a wide-open, heretical, and humanistic religion be found in dogma, doctrine, or confessions. He proclaims, in agreement with friend and fellow naturalist John Burroughs, that a living religion (belief system, worldview) cannot be centered in theology at all.

What does Muir say about heaven? That’s fairly simple: we’re already there; it’s already here. Nothing supernatural at all. On hell, he once said that if hell were a dark, rocky pit, he’d climb right out of it. We, all by ourselves, create something hellish when we bring suffering on our fellow inhabitants on the spinning—and warming—globe. Nature makes heaven; we make hell.

Muir’s radical faith is both sensible and sapient: faith is rational, heuristic pleasure in the wonder of the world. Nothing more, nothing less. For him, a solitary or social experience with wilderness occurs where the wild things are the congregation and we are the ones who must join it. Such wildness can be found deep in a national park or in our own garden.

In My First Summer in the Sierras (1911), he climbs Cathedral Peak in the Sierras and testifies:

This I may say is the first time I have been at church in California, led here at last, every door graciously opened for the poor lonely worshiper. In our best times everything turns into religion, all the world seems a church and the mountains altars.

While many happily nontheistic travelers will balk at the notion that at our zenith everything “turns into religion,” consider how this secular saint leads us to what could be a new kind of natural religion, or, and I doubt he would be very shocked, to the end of anything we’ve known as religion.

One is constantly reminded of the infinite lavishness and fertility of nature—inexhaustible abundance amid what seems enormous waste. And yet when we look into any of its operations that lie within reach of our minds, we learn that no particle of its material is wasted or worn out. It is eternally flowing from use to use, beauty to yet higher beauty; and we soon cease to lament waste and death, and rather rejoice and exult in the imperishable, unspendable wealth of the universe, and faithfully watch and wait the reappearance of everything that melts and fades and dies about us, feeling sure that its next appearance will be better and more beautiful than the last.

While the final sentiment in that passage sounds discordant in terms of our modern climate crisis, we can enlist Muir in directly addressing our critical environmental crises today. We need him to remind us of two essentials to pack along: first, we have to meet on common ground (say a city, state, or national park), focused on the beauty at hand, regardless of our divisive views. And second, it’s not just about beauty.

Writing to his sister Sarah in 1873, Muir penned the words we find emblazoned on t-shirts and posters: “The mountains are calling and I must go.” Yet he follows this with: “And I will work on while I can, studying incessantly.” Beauty is not merely for recreation and contemplation, it is an invitation to learn more, conserve more, preserve more. This takes devoted work and study.

As Muir’s close friend Robert Underwood Johnson wrote after Muir’s death, “[People] will search for beauty as scientists search for truth, knowing that while truth can make one free, it is beauty of some sort … that alone can give permanent happiness.” Preserving wild spaces is preserving the beauty, and ourselves.

In this regard Muir would be a leader in presenting solutions to our climate crisis. He would identify it as a consciousness crisis first, then entice us into the beauty, both the marred and the marvelous, demanding we “work on; study incessantly.”

In his 1915 work, Travels in Alaska, the great naturalist stands in the pristine paradise of Alaska and exults:

When we contemplate the whole globe as one great dewdrop, striped and dotted with continents and islands, flying through space with other stars all singing and shining together as one, the whole universe appears as an infinite storm of beauty.

The whole tiny globe is like a drop of water spilling through limitless space, one star among countless stars. And when we contemplate and contextualize this, what do we see? How do we feel? What is humanity that anyone should be mindful of us?

For Muir, and potentially for us, the universe presents itself as “an infinite storm of beauty.” The “call” and “mission” is to learn from the storms whether destructive or creative—to better understand our world and be wiser participants in the grand show.

John Muir’s radical religion of beauty, stirring education, environmental action, and awe-inspiring emotional connection to all things earthly, may serve to be the most natural bridge for humanists and religionists to explore. Though most of us have left the God-language behind, we can appreciate the trailblazing work of Muir to point us toward something more profound and practical than any religion has ever been.

If the wild Scotsman was correct, that “wildness is a necessity,” that “mountains are fountains of life,” then going out and up is our best hope for a humanistic future. Muir’s “gospel of beauty” represents the essence of humanism’s goals, and we don’t have to be mountain climbers (or have bushy beards) to saunter in his footsteps and beyond.