Nothing Sacred: What We Talk about When We Talk about Torture

The prisoners had their feet shackled to the floor and their hands cuffed close to their chins… Detainees were clad only in diapers and not allowed to feed themselves. A prisoner who started to drift off to sleep would tilt over and be caught by his chains. At one point, the agency was allowed to keep prisoners awake for as long as eleven days; the limit was later reduced to just over a week.

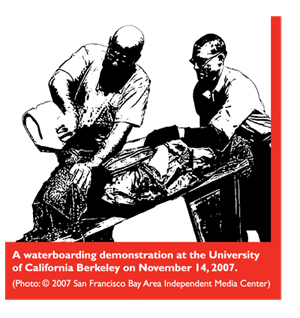

Waterboarding is now the most infamous torture technique practiced by the administration of George W. Bush. But Assistant Attorney General Jay Bybee’s August 1, 2002, memo—one of four President Obama released in April that had provided the legal basis for the CIA’s use of torture—authorized ten different torture techniques. One of which was sleep deprivation, as described in the above excerpt from a May 10, 2009, Los Angeles Times article.

According to that report, sleep deprivation was used in this manner on at least twenty-five detainees. And the Justice Department actually classified this torture method as less coercive than the other techniques, intending it to be employed earlier in the interrogation process. Other authorized techniques included slamming the detainee into the wall, slapping the detainee in the face, and confining the detainee in a small, dark space (Bybee wrote that if the space was so small that the person couldn’t stand, then only two hours of confinement at a time were authorized; if there was standing room, the detainee could be left in confinement for up to eighteen hours). Placing the detainee in stress positions and confining the detainee in a cramped space with an insect to induce fear were also listed, along with the now infamous waterboarding. The process is often described as “simulated drowning,” but voluntary waterboarding victim Christopher Hitchens, reflecting on his experience in the August 2008 issue of Vanity Fair, wrote:

You may have read by now the official lie about this treatment, which is that it “simulates” the feeling of drowning. This is not the case. You feel that you are drowning because you are drowning—or, rather, being drowned, albeit slowly and under controlled conditions and at the mercy (or otherwise) of those who are applying the pressure.

Hitchens, unlike the detainees in U.S. custody, was able to give a prearranged signal to the experienced military trainers and have the procedure halted. He wrote, “If waterboarding does not constitute torture, then there is no such thing as torture.”

In light of this, it’s difficult to comprehend that anyone in a position of authority in America can get away with calling these practices anything but torture, and also hard to believe there’s a debate taking place at all over whether or not the torture outlined in the Office of Legal Counsel memos is justifiable. However, in a survey published on April 29, the Pew Forum found that 49 percent of the U.S. public believes that torture can sometimes or often be justified. Among white evangelical Protestants, this number climbs to 62 percent. The Pew Forum didn’t carry out the survey using a euphemism such as “enhanced interrogation techniques” or another such watered-down phrase. Respondents were actually endorsing torture.

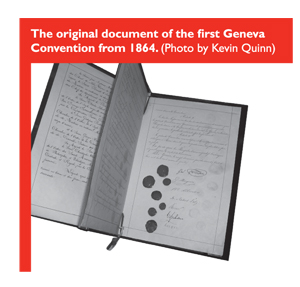

It’s a sign of just how distorted the American view of human rights has become when nearly 50 percent of the population supports interrogation methods that were banned in 1949 by the Geneva Convention concerning the treatment of prisoners of war. But why is there even higher support among evangelicals? Does a bible-based focus on the pain and suffering inflicted by an authority figure desensitize them? Is it that a feeling of insecurity about the world leads people to evangelical Christianity along with a “do whatever it takes to keep us safe” mentality? Does the Bible actually sanction torture at the hands of the state?

One possible answer was given by David Neff, the editor of Christianity Today and chairman of the board of the National Association of Evangelicals. Noting that most churches had not addressed the issue of torture at all, he told the Associated Press that among a lot of evangelicals “There is a sense of, ‘We trust this administration that was leading us through this difficult time post-9/11, and if they say we have to do this, chances are that sometimes it’s necessary.’” In other words, the evangelicals’ closeness to the Republican Party and the Bush administration led many of them to take Bush’s word for it that torture was both necessary and justified (even as administration officials never admitted that it was, in fact, torture that they were committing). After all, the Pew Forum also found that 64 percent of Republicans thought that torture was sometimes or often justified, as opposed to only 36 percent of Democrats. It appears that the evangelicals are coming down on the same side of the partisan divide as they usually do on other issues. Having put their trust in Bush & Co., perhaps they will not allow themselves to now question actions that were committed by them, even if it was torture.

Religious opinion on torture is by no means monolithic, however. Several days after the Pew Forum survey was released, the On Faithsection of the Washington Post’s website offered different religious leaders a chance to articulate their positions on torture. And indeed, examining their answers, it is clear that several of the religious leaders were unable to separate out politics from theology when addressing the issue, even when they did condemn torture. For example, Christian theologian and philosopher John Mark Reynolds of Biola University wrote, “Torture of any human being is incompatible with the Christian faith.” But after that direct answer, he goes on to spend most of his short essay wondering whether or not what the United States did actually was, in fact, torture:

Reasonable people can disagree about exactly what torture is and some believe that what the Bush administration ordered in prosecuting the War on Terror was not torture. They should be heard and not ignored, but so far the arguments advanced have not been persuasive.

I find it interesting that he dwells on this point after so much information describing the techniques that were authorized and put into practice by the Bush administration, including the Bybee and Bradbury memos, has been released. It suggests that this conservative theologian is having difficulty separating his politics from his moral view that no other human being should ever be tortured.

Chuck Colson, founder of the Prison Fellowship Ministry and former special counsel for Richard Nixon, follows a similar vein, also fixating in his brief piece on the question of whether or not the Bush administration actually tortured. He writes, “The real question in war time is what kind of behavior constitutes torture? That seems to me to be a factual question before it is a theological question.” Perhaps he didn’t have time to adequately enlighten himself as to the nature of what the Bush administration did in the interrogation rooms of Guantanamo and elsewhere. But even so, I find it odd that he refuses to address torture as a religious issue. Again, this reflects politics more than it does religious belief.

And, perhaps reflecting the change in prevailing opinion, or maybe even a change in heart, Richard Land, the head of the Southern Baptist Convention’s Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, recently came out strongly against torture. Speaking to Religion News Service on May 6, Land said that he considers waterboarding to be torture and that torture “violates everything that we stand for.” Addressing the issue of whether or not torture techniques were successful at obtaining information from detainees, he said, “If the end justifies the means, then where do you draw the line? It’s a moveable line…I believe there are absolutes. There are some things we must never do.” However, according to EthicsDaily.com, a division of the Baptist Center for Ethics, Land previously had criticized the National Association of Evangelicals for adopting an anti-torture statement in 2007 and had defended aggressive interrogations. He also called the Abu Ghraib revelations of 2004 an “aberration,” and while he supported prosecutions for the perpetrators, he classified the crimes as abuse rather than torture. EthicsDaily.com points out that Richard Land was very close to the Bush administration during its years in power. Could there be a political dimension to the fact that he hadn’t spoken out against torture before?

Some religious leaders have been able to completely set aside politics when addressing torture. Gabriel Salguero, a Christian theologian with the Princeton Theological Seminary, strongly condemns torture in the On Faithdiscussion and says it’s incompatible with Christianity. He points out that great people in history, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. among them, have chosen not to meet the violence of their adversaries with equal violence.

Some religious leaders have been able to completely set aside politics when addressing torture. Gabriel Salguero, a Christian theologian with the Princeton Theological Seminary, strongly condemns torture in the On Faithdiscussion and says it’s incompatible with Christianity. He points out that great people in history, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. among them, have chosen not to meet the violence of their adversaries with equal violence.

Indeed, revered figures and brave groups of people have stood up to injustice and tyranny without resorting to the techniques of their oppressors. They have held the moral high ground without conceding the battle. I wish that the United States had taken this approach in the face of terrorism rather than quickly employing torture and secret prisons, and disregarding the rule of law as if it were not central to the task, but rather an impediment to safeguarding our nation in the face of danger.

For his part, Rabbi Brad Hirschfield (an author, radio and TV talk show host, and president of the National Jewish Center for Learning and Leadership) wants everyone, on all sides of the issue, to examine it a little more closely:

Imagine for a moment that you knew the life of someone you loved, your child for example, would be saved by information extracted by torture. Are you really certain that you might not suddenly find some justification which allowed it “just this once”? Anyone answering “no” too quickly is either kidding themselves or doesn’t know the meaning of loving someone close to themselves.

Although this sounds like Hirschfield is defending torture, he quickly states that he isn’t; rather, he says:

I am more concerned about the endless moralizing around tough issues which makes them seem too easy too fast. In fact, that’s the style of argument which typifies those who defend the use of torture. Their arguments pose the question about saving a life as if we could know with certainty beforehand that the torture for which they advocate would save a life in immediate danger. I wish it were that simple, but it rarely, if ever, is.

No matter how many times the torture advocates talk about it, we have yet to encounter a so-called “ticking time bomb” scenario, one where, perhaps, the deactivation code to the bomb needs to be tortured out of some single suspect in custody before an entire city explodes. Television shows like 24 aside, under the Bush administration torture was committed with much more dubious goals than extracting the location of a bomb located under the city.

Rabbi Hirschfield’s point about these over-simplistic arguments being used to justify torture is well taken. Nevertheless, he may be trying a little too hard to be balanced with his consideration for why someone might support torture. Surely, if the life of my child was at stake, I might justify any number of horrible things to be done if it might save his or her life; this hypothetical situation, however, doesn’t add much to a discussion on human rights. It may provide some perspective on how we react to the idea of torture, but the actual laws that codify the preservation of human rights must be written under more level-headed circumstances than how you would feel if your child’s life was immediately at risk.

Much of this discussion, whether in favor or opposed to torture, nevertheless presupposes that the Bush Administration’s given reasons for implementing torture techniques—namely to extract information from dangerous terrorists on pending plots against America—are true. Former Vice President Dick Cheney, who has launched a vigorous public relations campaign defending torture (while never, of course, referring to it as such), told Bob Schieffer of CBS in a May 10 interview that, regarding the Bush administration’s interrogation methods, “I am convinced, absolutely convinced, that we saved thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands, of lives.”

But there is a growing body of evidence that, in the run up to the March 2003 invasion of Iraq, the Bush administration was implementing torture in order to elicit information linking Saddam Hussein’s regime to al Qaeda and the September 11 attacks. In a piece posted on The Washington Note blog on May 13, Col. Lawrence Wilkerson, State Department Chief of Staff during Colin Powell’s term as Secretary of State, wrote that during his own investigations into harsh interrogations that had been carried out in April and May of 2002, he learned that the administration’s “principal priority for intelligence was not aimed at pre-empting another terrorist attack on the U.S. but discovering a smoking gun linking Iraq and al-Qa’ida.” He went on to say:

So furious was this effort that on one particular detainee, even when the interrogation team had reported to Cheney’s office that their detainee “was compliant” (meaning the team recommended no more torture), the VP’s office ordered them to continue the enhanced methods. The detainee had not revealed any al-Qa’ida-Baghdad contacts yet. This ceased only after Ibn al-Shaykh al-Libi, under waterboarding in Egypt, “revealed” such contacts. Of course later we learned that al-Libi revealed these contacts only to get the torture to stop. …There in fact were no such contacts.

This assertion corroborates an April 21 report from McClatchy Newspapers. Requesting anonymity, a former senior U.S. intelligence official told McClatchy that in 2002 and 2003, Cheney and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld were demanding that interrogators find a link between al Qaeda and Saddam Hussein’s regime. He said, “There was constant pressure on the intelligence agencies and the interrogators to do whatever it took to get that information out of the detainees, especially the few high-value ones we had, and when people kept coming up empty, they were told by Cheney’s and Rumsfeld’s people to push harder.” Indeed, this was the exact period of time when two of the supposed high-value detainees were waterboarded an astonishing number of times—the recently released Justice Department memos show that in August 2002 Abu Zubaydah was waterboarded at least eighty-three times, while Khalid Sheik Muhammed was waterboarded 183 times in March of 2003.

And if the Bush administration really had wanted information on impending terrorist attacks, would they have used torture techniques that have been used throughout history to elicit false confessions? Testifying to the Senate Judiciary Committee on May 13, former FBI interrogator Ali Soufan relayed his experience interrogating different suspected terrorists using entirely lawful means and argued that the torture techniques implemented by the CIA were “ineffective, slow, and unreliable.” He described his initial interrogation of the alleged al Qaeda operative Abu Zubaydah using traditional and lawful techniques and how he was able to discover the connections to Khalid Sheik Muhammed and Jose Padilla in this manner. But he stated that later the CIA stepped in to perform harsh interrogations, and eventually the FBI withdrew altogether because it would not participate in torture. Ali Soufan argued that the best intelligence came from the lawful interrogations, while torture elicited only unreliable statements from Abu Zubaydah. If that’s the case, why would the Bush administration rely on such ineffective techniques to keep America safe? If the true intent was connecting Saddam Hussein to al Qaeda and September 11, then it is clear that the Bush administration was less interested in veracity and more interested in hearing the right words. They were seeking false confessions.

If this is true—if the Bush administration tortured in many cases to link Iraq to international terrorism to support its case for invasion rather than to uncover terrorist plots against the United States—are there any scenarios where torture would, in fact, be the right answer? Could it ever be justifiable? How does a humanist perspective apply? Faced with Dick Cheney’s pronouncements that torture saved American lives, where can a humanist stand when raising an objection to torture if his statement is true?

If this is true—if the Bush administration tortured in many cases to link Iraq to international terrorism to support its case for invasion rather than to uncover terrorist plots against the United States—are there any scenarios where torture would, in fact, be the right answer? Could it ever be justifiable? How does a humanist perspective apply? Faced with Dick Cheney’s pronouncements that torture saved American lives, where can a humanist stand when raising an objection to torture if his statement is true?

First, one must recognize that, even though humanists are often accused of practicing moral relativism, this simply isn’t true. Humanists recognize that ethical values originate from human need. And these values are, as Humanist Manifesto III states, tested against experience. This has been a human evolutionary process, and we have now had thousands of years to work on it.

And yet, despite the vastness of time, space, and human cultural diversity, we nevertheless are led towards certain widespread ethical ideas. That most humanistic of ethical aphorisms, the Ethic of Reciprocity (also known as the Golden Rule), appears in ancient Greek philosophy and can be found in nearly every major religion. Its universality suggests that humans have tested it over the centuries against experience and found it to be both useful and desirable.

Humanism historically has stood on the idea that every individual human being must be treated as having “inherent worth and dignity” (a phrase also taken from Humanist Manifesto III). I read this phrase as having, on the one hand, some roots in the Ethic of Reciprocity, because we would all like to be treated as having inherent worth and dignity; we would like our humane treatment of others to be reciprocated to ourselves. But treating people this way also has a value in and of itself that needs no further justification. It is the recognition of the solidarity of the human species and a rejection of the very relativism of which humanists are often accused. It’s like this: human beings deserve humane treatment by virtue of being human; we have no godlike powers to determine who is worthy of humane treatment and who is worthy of being treated as less than human. Human rights must be universal to have any meaning at all. Otherwise they are only a mechanism to privilege some humans over others.

Important historical (and legally binding) human rights documents recognize this and explicitly recognize this universality. There is no provision in the Bill of Rights that the rights of those accused of the most heinous crimes shall not need to be respected. To the contrary: most of the ten amendments in the Bill of Rights deal specifically with defining the rights of the accused, including the Eighth Amendment, which prohibits cruel and unusual punishment. Both the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the UN Convention Against Torture (to which 146 nations are a party) specifically prohibit torture under all circumstances, and the latter document makes clear that no exceptions may be made for times of war, instability, or emergency. As inspiring as it is to see the humanist precept of universal rights enshrined in these documents, it is all the more distressing that so many governments (including our own) fail to uphold them.

We do not endow human beings with godlike powers over other human beings—the power to cause untold suffering, the power to destroy a person from within and without, to crumble their personhood, to permanently disfigure their bodies and their minds. By virtue of having been born, a person has a right to the dignity and rights that we afford all members of our species. This does not interfere with our ability to hold terrorists accountable for their actions. Rather, it legitimizes that very process of accountability. Terrorists, having acted outside the law, should be brought inside it. No matter the rhetorical devices directed against them, they are still human beings.

We cannot turn back the clock, but hope is not lost for moving forward with dignity. We must hold the torturers accountable. And if, in the human and legal wreckage left behind by the torture regime, we can still salvage cases against those who are still in custody, then we should proceed forward, bring them to court, respect international standards for the admissibility (and inadmissibility) of evidence garnered by illegal means, and see to it that justice is served. And those who designed, authorized, and carried out this illegal torture regime should likewise be investigated and brought to justice. For without the accountability of the court of law, we cannot be certain that torture will not be committed in the future in the name of the United States of America.