You Don’t Know Jack

Reporter: There are those who would say about Dr. Jack Kevorkian: “Right message; wrong messenger.”

Geoffrey Fieger: And who is the right messenger?

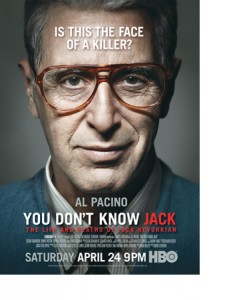

These lines sum up the dilemma posed by You Don’t Know Jack, the Home Box Office movie that premiered April 15, 2010, at the Ziegfield Theater in New York City and first aired April 24 on HBO. Through Al Pacino’s brilliant portrayal of Murad “Jack” Kevorkian, we come to realize that we don’t get to choose our heroes. And our heroes don’t get to choose the conditions under which they must struggle for their ideals.

As Susan Sarandon (who plays Hemlock activist Janet Good in the film) points out in a promo, we witness a man with faults, eccentricities, and a huge ego—a man who is outrageous and doesn’t really care. And a man who, while trying to succeed, is sometimes his own worst enemy. But this gives us the human side of the story. We meet the Dr. Kevorkian we never knew, a guy who methodically cuts the fat off of the turkey he’s served in a restaurant, who doesn’t care that people overhear his private conversations, who is afraid of flying, and who beautifully plays the flute to assuage his grief when his sister Margo (Brenda Vaccaro) dies. We also witness his grandstanding through hunger strikes, putting himself in a pillory to protest the charge that he’s violated the common law, and his engagement in courtroom theatrics. When Mike Wallace asks him on 60 Minutes if he’s a “fanatic,” Kevorkian corrects him. “Zealot,” he says.

We also get to see Kevorkian’s forthrightness in challenging the religious ideas that inspired those who opposed, and still oppose, his work (incidentally, he received the Humanist Hero award from the American Humanist Association in 1994):

Protester: Only God can create and destroy. Have you no religion; have you no god?

Kevorkian: Oh I do, lady. I have a religion. His name is Bach, Johann Sebastian Bach. And at least my god isn’t an invented one.”

Another featured role is that of Kevorkian’s headstrong attorney, Geoffrey Fieger, played spot-on by Danny Huston (and I say that with some knowledge, having met the man, as well as Kevorkian himself).

But the conditions of the times offer the greatest obstacles to Kevorkian’s achievements. Although the former pathologist would prefer that patients get second and third opinions, receive psychological or psychiatric counseling, even consult with the clergy of their choice prior to seeking physician-assisted voluntary euthanasia, this level of interdisciplinary cooperation didn’t exist in the 1990s. Kevorkian had to act in isolation.

This is why we see him buying some of the materials for his famous “mercitron machine” at a rummage sale: used Erector Set parts, and explaining to his med tech assistant, Neal Nicol (played by John Goodman), that the reason he knows the device will work—though he hasn’t tested it—is “because I built it myself.” We see him forced to perform his first assisted suicide in the back of a Volkswagon bus parked near a lake. At other times he and Nicol use motel rooms and then let the police come and retrieve the bodies, or they drop the bodies off in front of hospitals. When he needs a lawyer, his sister recommends one she’s seen on television doing medical malpractice commercials. And after his physician’s license is revoked and he can no longer make purchases from medical supply outlets, Kevorkian tries to conserve the lethal gas he uses with a jury-rigged hood made out of a cardboard box and plastic, with distressing results.

Adam Mazer’s screenplay is carefully fashioned throughout. The approach is objective and with a clear respect shown to those portrayed. But it also has humor, and serious points are deftly interspersed between trivial details, all delivered through the quirky personalities of the various characters.

Kevorkian and Fieger passionately argue for self-determination as a basic right. Kevorkian makes it plain that he puts his ethics first, turning down 97 to 98 percent of those who come to him seeking his help in their desire to die. And he boldly declares to a reporter, while seated in a booth at a crowded restaurant, that the practice of taking people off life support is brutal and inhumane: “They cut off their feeding and their water. And they let ‘em die. And it’s all legal. The United States Supreme Court has validated the Nazi method of execution.”

Why, he wonders, don’t people think it better to let the terminally ill choose a quick and painless death?

A special feature of the film is how Oscar-winning director Barry Levinson uses actual interview videos of Kevorkian’s patients telling their stories, cleverly using computer image technology to insert Pacino into the scene where the real Kevorkian had been. Thus we see not just great acting, but genuine feeling as expressed by real people. We see what the jurors saw who acquitted “Doctor Death” on more than one occasion.

The story takes us up through Kevorkian’s 1999 conviction in his fifth trial, followed by his receipt of the maximum sentence of ten to twenty-five years for second degree murder and delivery of a controlled substance. We see him entering prison and then learn from text at the end that the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear his appeal, resulting in his serving eight-and-a-half years before his release in 2007 at the age of seventy-nine.

Despite all this effort at accuracy, however, we must remember that no matter how realistic a dramatic film attempts to be, it must remain, at root, a work of fictional art. Real life just doesn’t fit neatly into the requirements of plot and pacing. And the people who populate historic events never seem to conform to the economy of characters needed so that a story can unfold coherently on the screen. Thus events have to be left out, others telescoped, multiple people must be consolidated into a few dramatis personae, and some have to be ignored altogether.

Never mentioned, for example, is Michael Alan Schwartz. Who was he? Kevorkian’s lawyer in every case that led to acquittal—perhaps the real brains behind the legal strategy—the other guy at the defense table. Schwartz was a former prosecutor turned criminal defense attorney. Fieger, however, headed the law firm. And in Kevorkian’s cases Fieger was often showman and publicist. In the real world, that’s often how things work.

But this situation opens opportunities for critics to charge inaccuracy in support of their own ideology. Hence those on Kevorkian’s side will have to take this into account. The HBO portrayal of the man and his cause can’t be treated as evidence. It isn’t a documentary. Rather it is a particular view of the whole matter.

But a view that this reviewer finds sympathetic, gratifying, and long overdue.