The Social Conquest of Earth

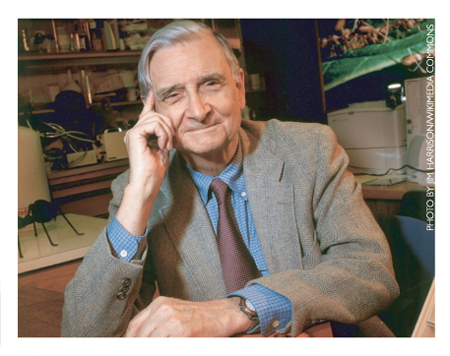

Edward O. Wilson’s latest book is structured around three questions: Where did we come from, what are we, and where are we going? Philosophers and theologians have been chewing on these questions for millennia, but subjectively—from inside the box, as it were. Only recently have our scientists generated enough hard, verifiable evidence about what we are and where we came from to allow us to step outside ourselves and describe our species objectively. Wilson has done an impressive job of pulling all this evidence together and analyzing it. His interdisciplinary approach, his established scholarship, and his willingness to engage hot-button issues are all much in evidence in The Social Conquest of Earth.

So, where did we come from? In answering this first question, Wilson gives us a readable description of our biological evolution, from our beginnings, when we split off from the chimps and the bonobos, to the present. It’s a story that has been told by others, but his narrative is useful, because it’s up to date in a rapidly evolving field; it’s fair, because he is clear about what’s proven versus what’s merely credible versus what is speculative; and the narrative is special, because he informs the whole of it with his broad understanding of other life forms.

Homo sapiens, says Wilson, is a highly complex species that has evolved from a series of lucky breaks, evolution-wise. No predestination here, we’re just damned fortunate to exist at all. At first there was a longish period of slow, adaptive changes during which human nature evolved together with the physical changes that made us recognizably human. Then came agriculture, and an explosive growth in complex cultures and social organizations. Our social patterns changed too rapidly for our human nature to keep up, bringing it into constant conflict with the more modern constraints required by large social groups.

Wilson concludes that we are a complicated lot, and for good reasons. If the complexities created problems for our forebears, they created opportunities as well. Some of the adaptations made by our remote ancestors fortuitously enabled later evolutionary changes that led us to cooperate in increasingly large social groups, and ultimately to achieve the condition we now know as civilization.

Wilson concludes that we are a complicated lot, and for good reasons. If the complexities created problems for our forebears, they created opportunities as well. Some of the adaptations made by our remote ancestors fortuitously enabled later evolutionary changes that led us to cooperate in increasingly large social groups, and ultimately to achieve the condition we now know as civilization.

It is this capacity for the evolution of large social groups that makes us special, according to Wilson. He uses the term “eusocial” to designate a species that has achieved this kind of evolutionary breakthrough, something that has only rarely occurred in our planet’s biosphere. (Wilson states his technical definition of eusociality, also known in some circles as “ultrasociality” as: “group members containing multiple generations and prone to perform altruistic acts as part of their division of labor.”) Certain ants and termites have achieved it, and a few other species, but Homo sapiens is the only large mammal to do so. Why and how did we, among all large mammals, achieve this condition? There is a story here, and it needs to be told. Indeed, it was Wilson’s main purpose in writing The Social Conquest of Earth.

Eusociality, in the rare instances it is achieved, evolves through the process called multi-level selection. That process entails evolution proceeding at both the group level and the individual level at the same time. Once it starts, the nature of the evolutionary process is transformed. It certainly was in our case.

The seeds of eusociality were planted in our species long before the dawn of agriculture, but once that happened and our numbers increased, all hell broke loose, so to speak. People joined together in various ways and for various reasons in ever larger groups, from villages to kingdoms to nation states. Competition between groups caused cultures to proliferate while culturally defined groups duked it out. It’s been a rough ride over the last ten thousand years, with wars virtually endemic and winners and losers all over the place. In fact, it’s still a rough ride.

When we think historically this way, it’s obvious that we’re looking at an evolutionary process that involves competition between groups, with success going to the winners. Many specialists in evolutionary theory, however, have a problem with looking at the process in simple evolutionary terms. Groups are composed of individuals who compete with each other. At that level, altruism is not a winning strategy. And yet, a functioning human society depends on its individuals acting altruistically enough, even at some personal cost, to support the larger interest of the community. What about the “selfish gene” principle? Can we posit a plausible mechanism that provides for altruistic behavior in groups composed of individuals genetically predisposed to behave selfishly?

Wilson’s explanation covers both how eusociality has emerged in some species, including ours, and why its emergence has been such a rarity. He postulates that evolutionary trends can at times create situations in which some minor genetic alteration can produce eusocial individuals. Other concurrent trends can produce environments in which eusocial behavior is beneficial to the group as a whole. If circumstances arise in which between-group selection becomes an appreciably stronger force than selection of individuals within the group, eusociality takes over. This is an exceedingly rare phenomenon, but, again, it happened to us.

Once eusociality takes over, it tends to perpetuate itself mainly because individuals benefit more from its existence than they would from its absence. Culture steps in to reinforce group identity. Religion becomes specialized, stressing group particularity. Recurrent wars with other groups kick the group selection aspect of eusociality into high gear. Ethical systems develop fancy ways of distinguishing between right (that which supports the commonality) and wrong (selfish behavior that undermines group strength and solidarity). All of this efflorescence, and much more, unfolds through the principle of competition between groups with rewards for the winners and more or less severe penalties for the losers. Meanwhile, competition continues at the individual level between the selfish and the altruistic. This is multi-level selection, operating at two levels.

At several points Wilson addresses the fact that multi-level selection theory is still rejected by a significant, if diminishing, portion of the scientific community. There are portions of his defense that are highly technical and presumably intended for his professional critics. I have tried to reduce them to non-technical language here. (For those wishing to explore the subject in more depth, this is a good place to start.)

For this review, let it suffice to say that the controversy is as yet unresolved, and one of the major critics of the whole multi-level selection theory is humanism’s good friend Richard Dawkins. It seems to this reviewer that the lines of disagreement may be getting blurred as the theory itself gets more refined. Possibly, consensus can be achieved on a scientific basis, rather than battle lines hardening as if it were a theological issue. If Wilson’s analysis helps toward this end, it will have served an important purpose above and beyond informing the public.

Wilson concludes his massive opus with a short section on the third of the basic questions, that is, “where are we going?” Sorry, those of you who were expecting some Star Trek-like scenario will be disappointed. The good professor thinks we should all get together and concentrate on terrestrial problems like climate change and species extinction, aimed at making our planet a paradise, while leaving outer space to itself. You may not agree, but his reflections on this subject are varied, original, and thought provoking—as is the rest of his book.