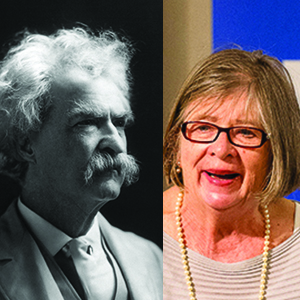

Skeptics Who See Things: The Curious Visions of Mark Twain and Barbara Ehrenreich

Ehrenreich Photo by Bruce F. Press Photography

Ehrenreich Photo by Bruce F. Press Photography MARK TWAIN, the revered American humorist and writer, was a famous skeptic and critic of organized religion. He wrote that “Faith is believing what you know ain’t so,” and that the Bible contains “upwards of a thousand lies.” An ardent abolitionist and supporter of women’s suffrage, Twain’s commitment to upholding human dignity and secular morality along with a healthy dose of skepticism makes “humanist” a more than accurate label for his worldview, even though he never described himself as such. However, Twain also became obsessed with what he saw as supernatural phenomena, creating an interesting dichotomy that can illuminate how modern humanists might react to experiences that are seemingly unexplainable from a scientific worldview.

In one story that haunted Twain for much of his life, he and his younger brother Henry secured jobs on the steamboat Pennsylvania in 1858. On the night before they went aboard, Twain dreamt that Henry was dead, lying in a metal casket wearing his older brother’s suit. In his hands was a bouquet of white roses with a single red rose in the middle. The steamboat’s journey commenced, but due to a disagreement with the pilot, Twain was transferred to a different boat while Henry stayed on the Pennsylvania. Shortly after, the boiler exploded, killing Henry. The women who worked at the funeral home were so moved by young Henry’s innocence and beauty that they gave him the most expensive metal casket and a borrowed suit. When Twain entered the viewing room to see his dead brother he was shocked by the uncanny resemblance to his dream. Then, as he mourned, a woman came in and placed a bouquet of white roses on Henry’s chest, then pulled out a red rose and placed it in the center of the bouquet.

This seemingly paranormal experience led Twain into the pseudoscientific world of “dream precognition.” In fact, he was one of the first people to join the Society for Psychical Research in hopes that it could provide him with some answers about his prophetical dream.

“I don’t know what brought the thought to me at that particular time instead of earlier, but I am well satisfied that it originated with the board of directors, and had been on its way to my brain through the air ever since the moment that saw their vote recorded.” – Mark Twain. Public Domain Image.

Twain also experienced an unfathomable number of coincidences in his life. Numerous times, upon realizing it had been a long while since he’d been in correspondence with a particular acquaintance, Twain would note that he should probably write a letter to that person in the near future. Then, without fail, the next day a letter would arrive from that very person. Twain even recounts one story in which he predicts, down to the number of steps he’ll take, exactly when and where he will run into an old friend. As a psychology student, I can’t help but wonder how much of Twain’s precognition was actually a combination of hindsight bias—the inclination, after an event has occurred, to say one could have predicted it all along—and confirmation bias, the tendency to pick out details that support your hypothesis or prediction while ignoring ones that contradict it.

The coincidences piled up until Twain decided they couldn’t be mere coincidences, so he proposed a mechanism called mental telegraphy. Mental telegraphy is the principle that “mind can act upon mind in a quite detailed and elaborate way over vast stretches of land and water,” as Twain himself remarks, that somehow one mind can influence another through thought alone. Of course, we now know that brain states are the result of electrochemical reactions, and that these reactions can’t be transferred magically from brain to brain.

In another story, Twain talks about having lunch at a social club in New York and being reminded of another club of which he’d long been a member but rarely had occasion to visit. He came up with the idea of asking them to forgo his membership fee by naming him an honorary member. Before Twain had a chance to share the idea he got a call from a friend notifying him that the club’s board of directors had decided to do just that. “What put the honorary membership in my head that day?” Twain wrote in an article titled “Mental Telegraphy Again.” “I don’t know what brought the thought to me at that particular time instead of earlier, but I am well satisfied that it originated with the board of directors, and had been on its way to my brain through the air ever since the moment that saw their vote recorded.” It seems just as likely that he and the board had the idea independently and it’s really not hard to imagine why because, after all, he was Mark Twain. Renowned people become accustomed to the elevated treatment they so often receive.

But what about when a commonsense explanation doesn’t come easily? Are rationalist types and atheists prone to wanting to discover it? Are some types unsettled by unexplained phenomena while others are comforted or even energized by them? For a long time “spiritual” was a dirty word among atheists. Recently, however, a debate has been raging within the secular movement about whether or not atheists can truly call themselves spiritual. While some high-profile thinkers such as Sam Harris have argued for a secular notion of spirituality, many skeptics remain, well, skeptical.

“There were no visions, no prophetic voices or visits by totemic animals, just this blazing everywhere. Something poured into me, and I poured out into it.” – Barbara Ehrenreich. Photo by Bruce F. Press Photography

In her new book, Living with a Wild God: A Nonbeliever’s Search for the Truth about Everything, Barbara Ehrenreich, a scientist and an atheist, discusses certain spiritual and mystical experiences she had as a teenager. In one such episode, she writes, “the world flamed into life.” She continues, “There were no visions, no prophetic voices or visits by totemic animals, just this blazing everywhere. Something poured into me, and I poured out into it.” As a rationally and scientifically minded person, I would be quick to point out that this so-called mystical experience can be reduced to certain electrochemical reactions in the brain that can be explained by any number of naturalistic and completely nonmystical causes. However, this reductionist argument ignores that, in a humanist paradigm, it’s the meaning that we as humans attach to such experiences that makes them spiritual, not their material origins.

It’s worth noting that Ehrenreich has qualms about the word “spirituality.” In her speech at the Women in Secularism III conference in May she said it sounds “like mush, like a surrender.” Certainly, “spirituality” has a lot of semantic baggage that it picked up after centuries of a religious monopoly on the word, and I agree with Ehrenreich’s intuition that replacing it with a different, secularized word would be a step forward. (I humbly nominate “awe” or “wonder” or perhaps even “yugen,” a Japanese word for a profound and deep appreciation for the wonder and mystery of the universe.)

Twain was certainly baffled by the role coincidence played in his life, but his “mental telegraphy” hypothesis at least indicates that he tried to make sense of the phenomenon, rather than be content with mystery. Similarly, Ehrenreich, in an interview about her book, stated that when people have unexplainable experiences “generally they say nothing or they label it as ‘God’ and get on with their lives. I’m saying, ‘Hey, no, let’s figure out what’s going on here.’” Perhaps the lesson to be learned is that spirituality is deeply ingrained into the human psyche. We, as humans, are hardwired to search for meaning when confronted with anomalous, puzzling, or emotionally fueled phenomena. However, regardless of whether you are comforted or confused by what might be described as mystical, unexplainable, or miraculous phenomena, the correct position to take is one of curiosity rather than complacency, of searching for the answers rather than invoking blind faith.