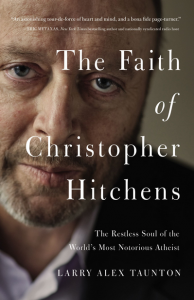

The Faith of Christopher Hitchens: The Restless Soul of the World’s Most Notorious Atheist

BOOK BY LARRY A. TAUNTON

THOMAS NELSON, 2016

224 PP.; $24.99 (KINDLE $12.99)

What would it take to convince you that prolific atheist Christopher Hitchens, toward the end of his life, had doubts about his lack of faith? Even more so, what would it take to convince you that not only did he begin to seriously question his lack of faith, but that he had begun the process of finding his religion? That his theological realignment went beyond the aristocratic deism of his American idols Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine to that of an uncozy-conscienced Christianity? That, in actuality, Hitchens was a kind of modern-day Nicodemus, seeing Jesus only in the twilights of the arguments he had with his evangelical friends, afraid to renounce his unbelief because it would mean a renunciation of his entire life—a life of “misanthropy, vanity, and excesses of every kind”?

It’s fair to say that the evidence required for such a thesis would have to be superabundant, well-documented, and offer up little room for fuzziness in regards to how it might be interpreted. After all, it was towards the end of his life that Hitchens became most energetic in his antipathy for the religious and supernatural impulses in others. It seems quite odd that he would, at this same time, be secretly beginning to feel those very impulses throbbing in himself.

In the absence of such compelling evidence, what would do as a suitable, if more speculative, replacement? If you’re thinking a tawdry Freudian biography, based loosely around two unrecorded car-trip conversations, riddled with contradictions and embarrassing errors, and lacking even a modicum of intellectual courage or fraternal decency, then Larry A. Taunton’s new book, The Faith of Christopher Hitchens: The Restless Soul of the World’s Most Notorious Atheist, will change forever the way you think about the man Taunton refers to as “one of atheism’s high priests.”

The essence of the book is simple enough. According to Taunton, there was both a private and a public Christopher Hitchens. The public Hitchens was a wit, a man of the Left, and a dismantler of false gods, religious or otherwise. He despised hypocrisy and cynicism, both of which indicated to him a lack of conviction, which was the ultimate and unforgiveable sin in his hamartiology. He was also certain of his materialistic worldview, if not of his out-and-out atheism. Often boorish and sadistic in his performances, he told Taunton on one of their car rides that his final rule for debates was deciding whether he “want[ed] to destroy the man or the argument.”

The private Hitchens, Taunton contends, was not so rough a beast. Nor was he so cocksure as he let on when there was an audience in view:

Publicly, he had to play the part, to pose, as a confident atheist—that was the side of the debate he’d been given, the one that made him both famous and rich. Privately, however, he was entering forbidden territory, crossing enemy lines, exploring what he had ignored or misrepresented for so long.

What is this grab bag of mixed-up metaphors meant to suggest for the reader? It’s that Christopher Hitchens became fearful of death after he was diagnosed with esophageal cancer and began to find the potential of an afterlife (which he surely saw as just a continuation of this life) appealing. Having for so long treated the religious right as a monolithic force in the political arena, The Faith of Christopher Hitchens suggests he was delighted to discover that, in many ways, the divisions and sectarianisms between and among Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Protestant denominations closely reflected those he had experienced during his radical youth. (A common rhetorical theme of Hitchens’s conversations with Christian apologists was him asking how they knew their guesswork was better than anyone else’s.)

Then there was the “aesthetic appreciation” Hitchens had for the King James Bible. While he might have found its science, morality, and history dubious, there was still the metaphorical fertility and pictorial language of its poetry that had to be reckoned with. And Hitchens, like two of his earlier heroes George Orwell and H. L. Mencken, could not deny the good book’s literary merits, whatever the claims made on its behalf about divine revelation. He even read from Paul’s Epistle to the Philippians at his own father’s funeral service. Compulsively, Taunton is shocked by this.

Finally, between his time not reading Richard Dawkins’ God Delusion and not taking Sam Harris’s pseudo-scientifically-garbed utilitarianism very seriously (both of which Taunton sees as scandals for a confessing atheist), Hitchens pined for a Church of England that took itself and its doctrines as holy writ once more. “The Archbishop of Canterbury has effectively endorsed the adoption of Sharia law,” Hitchens tells his travel partner, as relayed in the book. “Can you believe that?” he says to Taunton. “Whatever happened to a Church of England that believed in something?’ Upon hearing this, Taunton writes, his “eyebrows shot up” and he responds, “Why, Christopher, you sound nostalgic for a Church that actually took the Bible seriously.” Taunton continues: “He turned abruptly from the window, considered me for a moment, and smiled. ‘Indeed. Perhaps I do.’”

Hitchens often took ambiguity as a lack of earnestness at best and a sure sign of charlatanism at worst. Things were complicated, that much he agreed with. But those who made a profession out of pointing that out, without ever taking the conversation any further than calling for “more dialogue” were either showing their unwillingness to think critically on such matters or, more likely, showing their unwillingness to express held beliefs they couldn’t possibly defend. The interfaithful (those who, as Hitchens put it, “barely respect their own traditions and who look upon faith as just another word for community organizing”) have confused expanding their moral circle with minimizing their religion. So it’s little surprise he preferred the Talmudic Calvinism of his Collision co-star Douglas Wilson—or of a Church of England that made proclamations as if its clerisy actually believed eternal damnation were a possibility—to the religious outlook of another one of his debate opponents, Al Sharpton, a man of cloth minus the Christianity.

All this is enough to persuade Taunton that Hitchens was at least willing “to entertain the possibility, if only theoretically, to convert to Christianity.” Unfortunately, Taunton is stylistically too attached to the Chicken Soup for the Soul manner of writing that has so vulgarized popular Christian apologetics over the last three decades. Thus he is always heavy-handily bringing back up the central message of his book. And, with only so many ways of expressing the same thought, the severity of his accusations tends to fluctuate. At the end of each chapter we are led like Gloucester to the edge of a cliff, only to smack our faces on the short fall.

But if Taunton is right, and Hitchens was indeed on a path to conversion, why did he so painstakingly hide it even up to his death? A rather direct reply to this question is provided in the chapter that covers their so-called Bible study on the road from Washington, DC, to Birmingham, Alabama, where Hitchens was set to debate Oxford mathematics professor and philosopher of science John Lennox:

“I think that you have established a global reputation as an atheist,” I said. “It has come to define your public image. And it would take extraordinary courage to admit that you are wrong. I don’t envy that.” My answer was rapid, almost rehearsed, because I had considered the question many times.

His face, his body language, and his silence all suggested his acquiescence that this was, in fact, true.

Better than most, Hitchens could walk the fine line between disenfranchisement and apostasy—his writings on mundane cultural topics were always successful proofs of that—but it seems a bit more than merely wrong to recommend that what was holding him back from perhaps the conversion of the twenty-first century was fear of public backlash. His support for the invasion and occupation of Iraq was a jarring tune change, and he survived the backlash from that well enough.

Taunton’s recollection of the Bible study is itself gut-wrenching. Not for the insults or accusations battered off between co-pilots, but because of the patronizing cant in which he recalls the whole thing. “Plato and pupil” doesn’t quite capture the condescension:

“We’re trying to complete the thought, Christopher,” I said. “Perhaps by the time we get to Birmingham you’ll have something meaningful to say on that subject.”

Pair this with Taunton’s explanation for why Hitchens became an atheist in the first place—looking for license for his homosexuality and socialism, not to mention probably trying to impress his cosmopolitan mother—and one gets a decent measure of Taunton’s betrayal: for him, friendship is animus by other means.

Ultimately, the case of a dying man’s conversion put forward in The Faith of Christopher Hitchens adds up to not much. And like too many biographical studies, it reveals more about the author than the subject—in this case, how quickly its author will shoot for vilification, misrepresentation, or the cheap snigger-inducing remark. On page 45, we’re told Hitchens wasn’t a royalist, a conservative, or a military man because he spent his entire life rebelling against his father who was those things. Then, on page 47, we’re told it’s “hardly surprising” Hitchens wasn’t a Christian since his father wasn’t one either. So was his world outlook based on opposition to his father’s or wasn’t it? On page 5, we’re told that “one need only name the social or political issue of this period, and [Hitchens] was there to take up the liberal cause with other standard bearers of the Left.” Then, on page 27, we’re told “Christopher was a rebel, yes, but consistently so, rebelling against both Right and Left.” So which was he? Party liner or eternal rebel?

On page 71, we learn that 9/11 radicalized Hitchens into recognizing evil as a genuine problem. That is, until page 93, where we learn it caused his moral assumptions to be less Manichean. Before those attacks, Taunton writes, Hitchens explained away terrorism as “the result of a tangle of economic conditions, legitimate political grudges, understandable aspirations of underdogs, historical gripes, or cultural insults.” Except for in “Terrorism and Its Discontents,” a 1985 article from which Taunton quotes and thus implies he’s read, where Hitchens dismisses this very sort of crude reductionism: “Others will point suavely to the ‘root cause’ of unassuaged grievance. This is all right as far as it goes, which is not very far.” To say nothing of his contempt for those who would, in the name of anti-racism and anti-imperialism, slavishly lump together the concerns of Muslims worldwide as if they were an undifferentiated mass.

Oh yes, and that Bible for which Hitchens had a deep aesthetic appreciation according to Taunton? (An indication, you’ll remember, that he was perhaps a secret follower of Jesus.) Well, it turns out Taunton doubts he read much of it. Incidentally, he also doubts Hitchens read much Marx either. Considering Taunton’s tendency to cram everything he finds disagreeable with the world into something he calls “the Left,” he might benefit from thumbing through The Paris Commune himself. He had a Marxist friend who wrote an introduction to it once. That friend had courage and fine taste in books. It’s too bad he wasn’t around to tell Taunton to bury this one.