Tough Fluidity Complex considerations for trans youth

Snips and snails

And puppy-dogs’ tails

That’s what little boys are made of.

Sugar and spice

And all that’s nice

That’s what little girls are made of.

LAST YEAR WAS A BIG YEAR FOR “JAN.” She was in first grade and her parents had agreed to let her transition from her assigned gender, which was male, to the gender she identifies as, which is female. This is an enlightened age and Jan lives in an enlightened country (South Africa), and so her elementary school principal gathered the students and their parents around and informed everyone that Jan was now going to live as “a girl with boy bits.”

Jan’s mother explained how we’re all different and that she, Jan’s mother, is different because she has one foot bigger than the other. After the adults finished speaking, they asked if any of the children had questions. Two boys raised their hands. The first said he felt sorry for Jan.

“Oh?” said the principal. “But you know Jan wants to live as a girl and not a boy.”

“Yes,” he replied, “but that’s not why I’m sorry. I’m sorry for Jan because her mom has one foot bigger than the other.” And the other little boy? He said he knew exactly how Jan felt because he was half-fish.

The teachers didn’t know how to respond to an identity they hadn’t heard of, but okay—transgender, gender-fluid, half-fish—they weren’t going to judge. The gobsmacked response of the adults to the innocence of a child identifying as half-fish (because his mother said he swims like a fish) reveals why gender identity is such a hot topic; it’s part evolutionary debate, part human rights issue, part kindness and respect, and part sociological Wild West as we grapple with changing norms, changing language, and changing expectations.

A quick lesson to start. Many people confuse gender identity with sexual preference, but they’re two different things: gender identity is one’s own body image—the element that makes a boy identify as a boy, a girl identify as a girl, a girl identify as a boy, or vice versa—while sexual preference is the sexual identity of the person with whom one wants to have sex. So, your sexual identity may be cisgender male (with penis and testes intact) but your sexual preference can be gay.

Sexual identity is clearly complex, but everyone has a sex that is determined by three things:

1) The sex chromosomes—XY for boys and XX for females, and sometimes other variants, such as when girls have one X chromosome or an extra X chromosome and boys have an extra X chromosome. The chromosomes govern the synthesis of various hormones responsible for forming the gonads (the ovaries or testes), the genitals (the vagina and the penis), and the sexual parts of the brain. Our sex chromosomes are set at conception and do not change throughout our lives. Their action, however, can be influenced by hormones, including hormones administered by physicians.

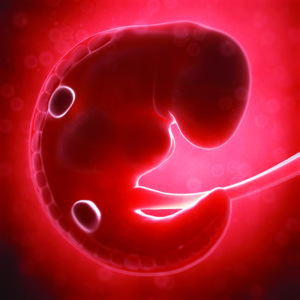

2) The sexual organs are undetermined during the first seven weeks of gestation. During this period, the basic architecture of the fetus is laid out fish-like: head to tail, right and left, and ventral to dorsal, and the tissues for the gonads are essentially there and starting their journey, but it’s not visually obvious if they will produce female or male sexual organs, or both, or neither. Over the next five weeks in utero, we can see the sexual organs beginning to develop. This process, known as differentiation, is controlled, for the most part, by hormones under the control of the sex chromosomes but is also influenced by the mother, the embryo itself, or other inhabitants of the womb, like a twin. So the development of the assigned sex, like every other trait, has both a genetic and environmental component. During puberty, which can take place anywhere from nine to sixteen years old, the secondary sexual characteristics develop, such as facial and pubic hair and increased muscle mass in men and curves, menstruation, and the development of breasts for women.

2) The sexual organs are undetermined during the first seven weeks of gestation. During this period, the basic architecture of the fetus is laid out fish-like: head to tail, right and left, and ventral to dorsal, and the tissues for the gonads are essentially there and starting their journey, but it’s not visually obvious if they will produce female or male sexual organs, or both, or neither. Over the next five weeks in utero, we can see the sexual organs beginning to develop. This process, known as differentiation, is controlled, for the most part, by hormones under the control of the sex chromosomes but is also influenced by the mother, the embryo itself, or other inhabitants of the womb, like a twin. So the development of the assigned sex, like every other trait, has both a genetic and environmental component. During puberty, which can take place anywhere from nine to sixteen years old, the secondary sexual characteristics develop, such as facial and pubic hair and increased muscle mass in men and curves, menstruation, and the development of breasts for women.

3) The third aspect of sex development is gender perception, which is a body image issue. This is tied into the structure of the brain and differences in the brain between men and women. Gender perception starts during the second half of pregnancy, when sexual differentiation of the brain begins. According to Dick F. Swaab and Alicia Garcia-Falgueras of the Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience in Amsterdam, “[S]ince sexual differentiation of the genitals takes place in the first two months of pregnancy and sexual differentiation of the brain starts in the second half of pregnancy, these two processes can be influenced independently, which may result in transsexuality.” As far as happiness and self-fulfillment are concerned, for everyone—transgender or cisgender—sexual perception is one of the most important elements of self and body image.

Which brings us to “Pat,” the daughter of a friend in my humanist group. Pat is ten years old and has healthy XY chromosomes and male sexual organs, but she has identified as a girl since she was three years old. My friend has two younger children who are cisgender (male) and says the gender difference between Pat and her brothers is stark. Pat is terrified of going through puberty. She doesn’t want to be fluid; she wants to grow up to be a woman and she wants her sexual organs and her outward appearance to match her identity. For my friend, trying to force her daughter to be a boy is as cruel and bizarre as trying to turn her cisgender children transgender.

While most people can understand the need for medical intervention for those whose genitals and chromosomes don’t match and have been assigned incorrectly at birth, even some of the most open-minded will balk at the concept of using a lab to allow a child with matching chromosomes and genitals but a different sexual identity to transition medically and hormonally. Here’s what Sexual Personae author, Camille Paglia (who self-identifies as a “transgender being”) told Sam Dorman of the Washington Free Beacon recently:

I am very concerned about current gender theory rhetoric that convinces young people that if they feel uneasy about or alienated from their assignment to one sex, then they must take concrete steps, from hormone therapy to alarmingly irreversible surgery, to become the other sex. I find this an oddly simplistic and indeed reactionary response to what should be regarded as a golden opportunity for flexibility and fluidity.

While Paglia might sound shockingly conservative for someone who has always lived her life in a way that has been true to her own sexual identity and politics, she’s actually being consistently liberal: she’s saying, in other words, feel free to live as a girl with a penis or as a boy with a vagina, or as a gay girl with a vagina or a lesbian boy with a penis, or whatever, but don’t get bogged down with trying to fit your parts into a binary identity of boxers or bikinis.

My friend “Mike” doesn’t agree. Mike is living his life as a male while identifying as a female. He’s heterosexual (i.e. he is attracted to women. Or, I ask, perhaps he’s a lesbian? “Maybe,” he says, after a pause), he’s married, and he has a daughter whom he adores. Yet for him, the feeling of being trapped in a male body has been brutal. It’s led to breakdowns and a psychiatric hospitalization. “If there’s anything I can do to help someone—child or adult—going through this pain, I’d do it,” he tells me.

When I first met Mike at a writing seminar almost ten years ago, I had no idea he was in such pain. He was inspired to come out of the closet by Caitlyn Jenner. If someone as high profile as Bruce Jenner could do it, and at an advanced age, so could he. (Of course, age is relative; Mike is only forty compared to Jenner’s sixty-seven.)

Mike still lives as a man without using hormones or having any genital reconstruction surgery. He currently has a beard for an acting role and he prefers to use masculine pronouns when referring to himself. But he’s most comfortable and at ease with his sexual identity when he’s clean-shaven, dressed in traditionally female clothes, and presenting himself as a woman. At these times Mike would like to be able to use female bathrooms. “The real intent of ‘bathroom bills,’” he says, “is to get people who want to protect women and children to support laws that won’t do anything in that area, but will actually have the effect of marginalizing trans people by making them feel unsafe in society because they won’t be able to use the bathroom in a public place.” Mike feels that as long as we have gender-specific bathrooms we should be able to use the one that matches the presented gender.

Some might scoff and say that makes Mike a cisgender white male who just likes to put on women’s clothing. Why can’t he just do that? Mike says it’s not the same. Living with gender dysphoria—a general state of unease about one’s biological sex—is agonizing for him. Growing up, he didn’t realize it was something he could change. And if he were eighteen now instead of forty, would he change? He says perhaps, but it’s a moot point and he wouldn’t want to erase the joy of being married and having a child. From now on out, however, he intends to live his life in the most authentic way possible. Transitioning might be a challenge to his relationship because his wife is cisgender, but that’s something they have to work on together—or apart—if it should come to that.

Transgender identity is not new. While it is well-known that many cis women in history have hidden their sexual assignment in the hopes of getting an education, professional acknowledgement, and even to go to war as soldiers, there are also documented cases of men and women who transitioned because of their gender identity. Judging from her self-portraits and family photographs, it’s possible that artist Freda Kahlo had a fluid gender identity even though she was married and had hoped to have children.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in Italy, the castrati were young boys who had voices that were deemed perfect, pure, angelic—and fleeting. Given all they’d put in to becoming great singers, it was a great honor for young boys on the verge of puberty to be chosen for castration, thereby preserving their pure, pre-puberty singing voices. Some were eager to submit to the knife. Losing human desire for love, sexuality, marriage, and fatherhood was nothing compared to the purity of protecting God’s voice personified. Sometimes they died, and sometimes the reverse metamorphosis didn’t take. What then for the neutered and deep-voiced man? There was always the priesthood to fall back on. After all, they were still men, and the church appreciated their chaste lifestyle.

While early castration is no longer considered moral or desirable, the transition from one’s assigned sex to one’s sexual identity is more controversial and is a complex process not everyone follows in the same order. Mike says that just because you haven’t undergone surgery or taken hormones, doesn’t mean you’re faking it.

For young people, the first step in transitioning to a different gender is made far easier if their family is understanding and allows them to live as their preferred identity with undeveloped sexual organs intact. This is known as socially transitioning and also requires a liberal school and state which will allow these children to use their preferred gender toilets and locker rooms, play in coed sports teams, and will educate the other children in the classroom about transgender rights and issues, as was done in Jan’s school. In the United States the Transgender Law Center ranks fourteen states plus DC as having a high gender-identity policy ranking, meaning they are tolerant of gender-identity issues, and twenty-three states as having negative gender-identity policies.

During puberty, the treatment becomes more difficult because this is when the secondary sex characteristics appear. Endocrinologists recommend the use of puberty blocking hormones, such as Lupron (leuproride), in order to protect voice quality and other gender-specific secondary sex characteristics until patients can become old enough to make an informed decision.

The so-called “pausing” of puberty is helpful and reversible but the benefits come with potentially serious risks—they are, after all, synthetic hormones. In the Washington Free Beacon article, Paglia issued a strong warning against the use of hormone blockers:

Because of my own personal odyssey, I am horrified by the escalating prescription of puberty-blockers to children with gender dysphoria like my own: I consider this practice to be a criminal violation of human rights. Have the adults gone mad? Children are now being callously used for fashionable medical experiments with unknown long-term results.

Some psychologists are also concerned that the use of puberty blockers can make transgender children feel left behind and even more isolated and different as their peers develop into young women or men.

There is another issue: according to several studies, a majority of gender-fluid children outgrow the need to transition. Their sexual preference may be gay or lesbian or bi or queer or cis, but ultimately their gender identity matches their assigned sex and they want their breasts or penises or hairy chests to stay put as chromosomes intended.

Doctors worry that the use of synthetic hormones to medically treat a gender-fluid identity can be harmful. There have been quite a few well-publicized misdiagnoses of gender dysmorphia that have fallen into the “first do no harm” category, leaving transsexuals feeling mutilated and desperately unhappy with the sex they have become. Indeed, the criteria for a gender dysmorphia diagnosis appears quite arbitrary and can be true for any number of LGBTQ+ or cisgender children, for example avoiding the assigned sex roles in play and showing a preference for the clothing, toys, and playmates of the opposite identified gender. A more telling criterion is when a transgender child insists from an early age that he/she is the identified sex, rather than wants to be the identified sex.

Beyond the possibility of a child reverting to their assigned gender, there’s another issue that terrifies parents like my humanist friend: according to the National Transgender Discrimination Survey, 41 percent of transgender adults have attempted suicide. It’s clear that the pain of gender dysmorphia is life-threatening and doctors realize the stakes. Using puberty blockers to help ease the transition into the third stage of gender reassignment is very helpful for a successful transition. And this is the path my humanist friend is allowing her daughter to pursue. Now that Pat is ten years old, she’s taking hormones prescribed by her doctor to postpone puberty and is living as a tween girl, wearing traditionally feminine clothes, using the girls’ locker room and bathroom at school, and playing on coed sports teams. The hormone treatment is paid for by their medical insurance.

Beyond the possibility of a child reverting to their assigned gender, there’s another issue that terrifies parents like my humanist friend: according to the National Transgender Discrimination Survey, 41 percent of transgender adults have attempted suicide. It’s clear that the pain of gender dysmorphia is life-threatening and doctors realize the stakes. Using puberty blockers to help ease the transition into the third stage of gender reassignment is very helpful for a successful transition. And this is the path my humanist friend is allowing her daughter to pursue. Now that Pat is ten years old, she’s taking hormones prescribed by her doctor to postpone puberty and is living as a tween girl, wearing traditionally feminine clothes, using the girls’ locker room and bathroom at school, and playing on coed sports teams. The hormone treatment is paid for by their medical insurance.

The third stage of gender reassignment happens after age sixteen when patients are given lifelong cross-gender hormones. These are serious drugs with serious and permanent side effects but they are also lifesaving for many transgender individuals, and many have made the informed decision to use them.

Gender reassignment surgery is the next stage, whereby surgeons are able to create a sexually satisfying penis or vagina for a patient. In 2016 the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine announced it would resume gender reassignment surgery after refusing to do so for thirty-five years. This is considered a major victory for transgender-rights activists. Other surgical options include facial surgery, breast removal or augmentation, and a new procedure where the vocal cords are operated on to raise the pitch of the voice for transwomen.

With or without surgery, high- profile celebrities like Chaz Bono, Caitlyn Jenner, and Laverne Cox have shown the joy of living in a body that matches their true sexual identity. They and others like them are inspiring many people, from fellow transgender people to cisgender me.